For a Friend Sorely Missed

This brief column can only begin to do justice to Iraqi poet and critic Moayyad al-Rawi. A longer tribute will appear in Al Jadid’s next issue later this year (Vol. 23, No. 77, 2019).

Moayyad, who died in 2015, fled the Iraqi dictatorship in 1970 for Lebanon, making it his first stop in a life in exile; it is there I met him. Imprisonment and repression following the 1963 Baathist coup forced him to leave Baghdad and Kirkuk, which he loved, and which figured prominently in his writings.

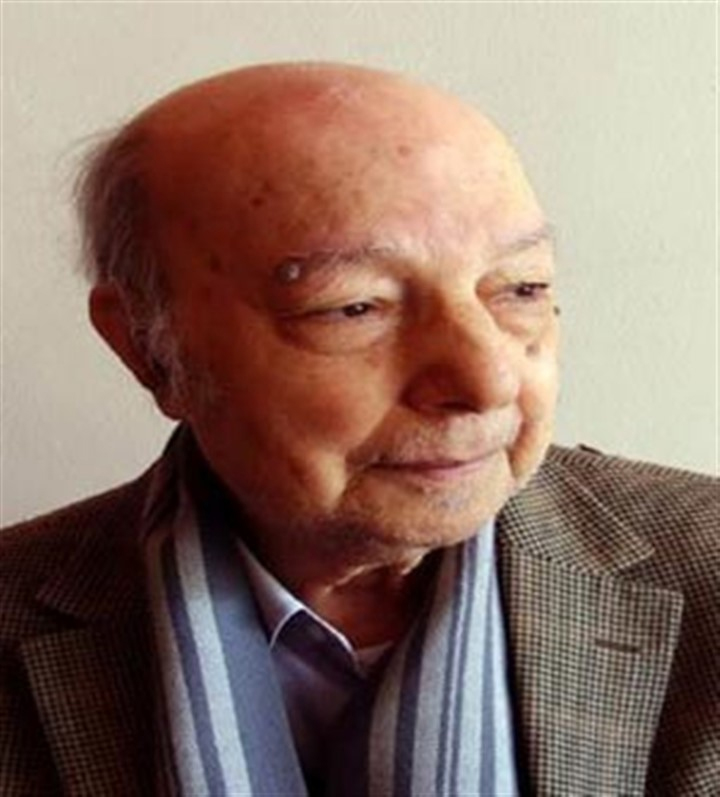

Ali al-Shawk in the Eyes of One Acquaintance

Ali al-Shawk’s death leaves an empty space that no one can fill. He was prolific, thoughtful, articulate, and of high manners. Personally, I thought of him as one of the most cultured intellectuals I have met inside or outside of Iraq. His cultural depth owed to the greatness and diversity of his reading, which included his fluent command of English, from which he translated several books.

‘Sexuality in the Arab World’: Book Attempts to Shed Multi-Faceted Light on Subject Long in the Shadows

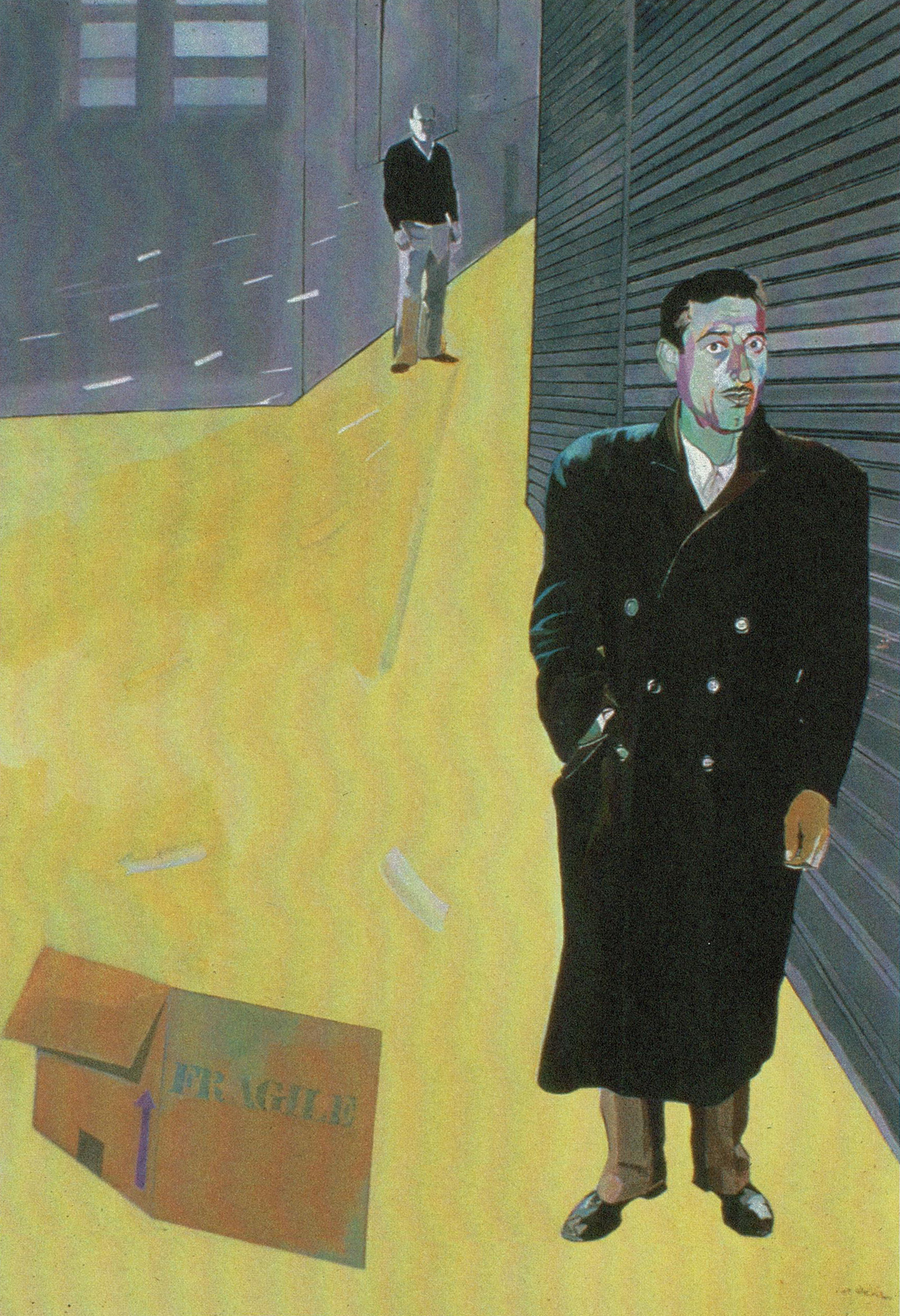

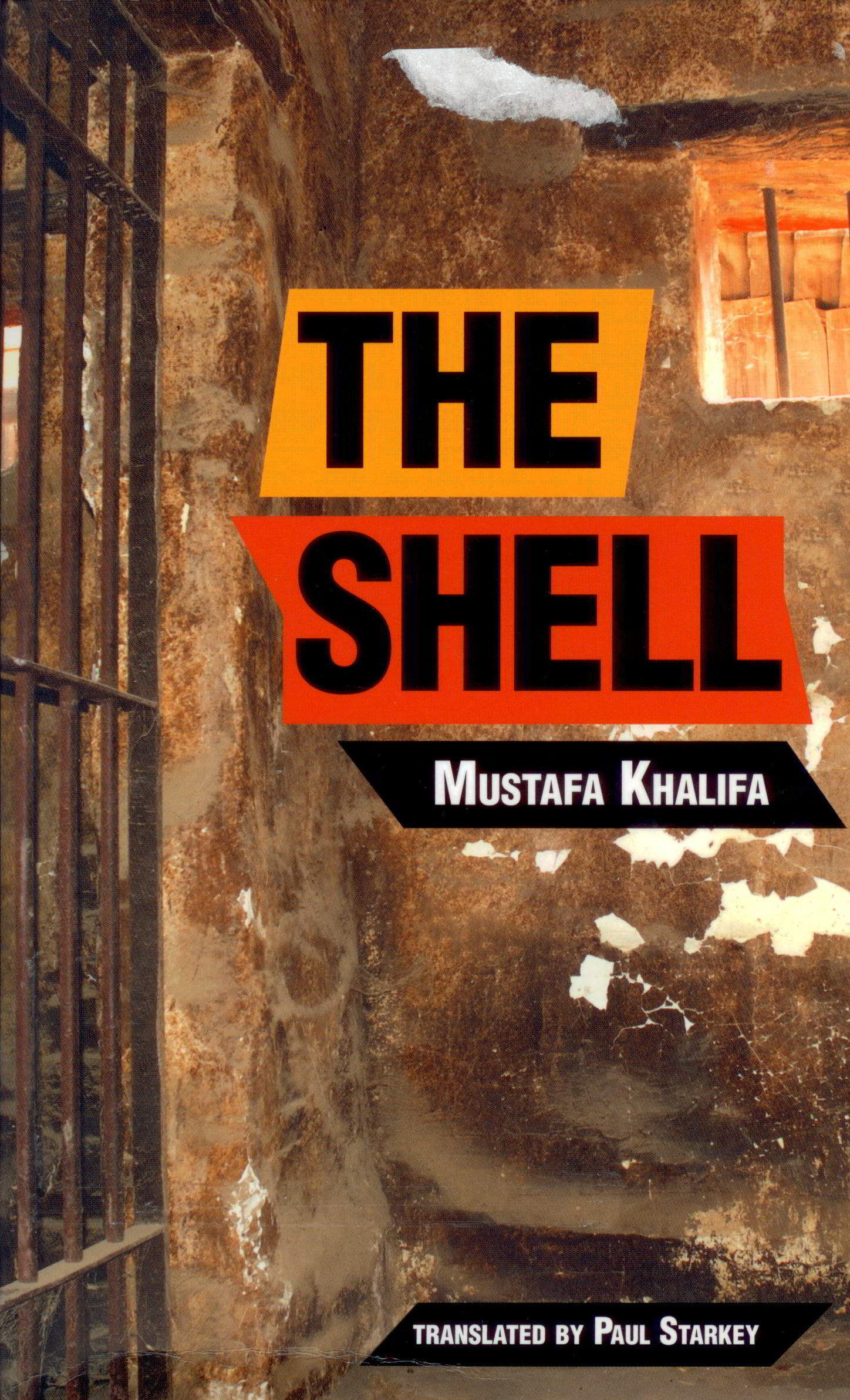

Mustafa Khalifa’s ‘The Shell’ Latest Example of Literature Offering Insight of Syrian Ordeal

A mere glance at the most notorious prisons in the world, Assad’s Tadmur moves to the forefront, ranking 2nd on a list of the 10 worst prisons. This is the prison which “hosted” Mustafa Khalifa, the author of “The Shell” for more than 13 years, and which Fawaz Azem reviews for the next issue of Al Jadid.