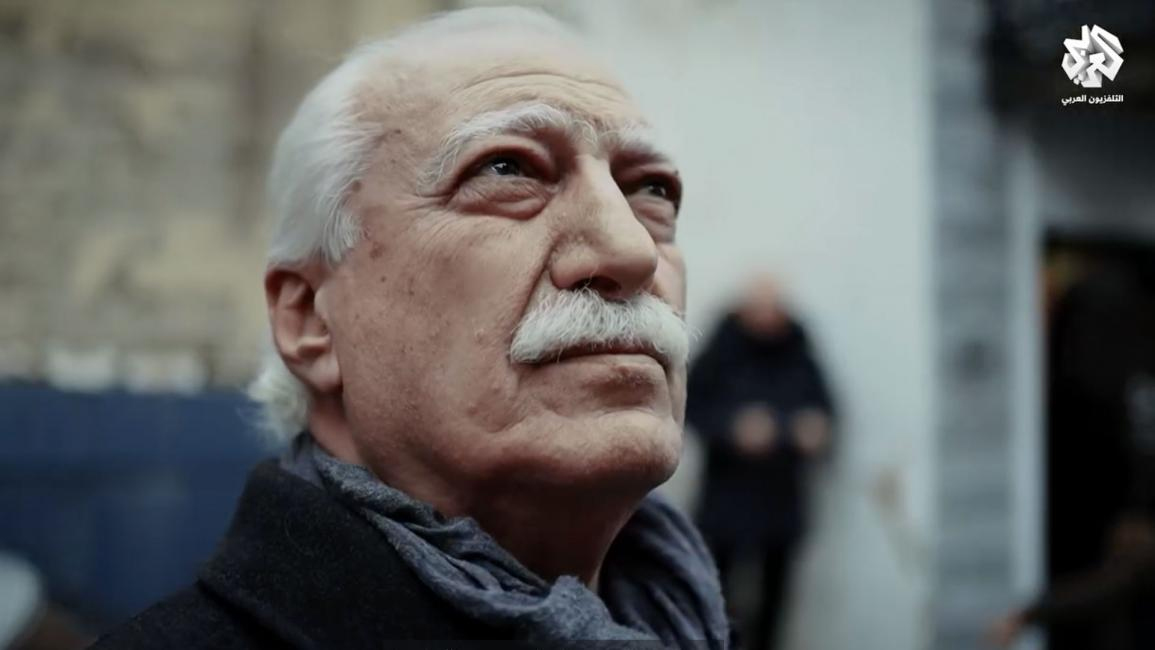

Photograph of Youssef Abdelki, courtesy of The New Arab.

Since the downfall of the Assad regime, Syria’s preeminent painter, Youssef Abdelki, has remained active in both the artistic and political spheres. Maen al-Bayyari honors the artist’s impactful contributions, calling for his recognition from the creative community in his essay, “Youssef Abdelki’s Obedient Tears,”* published in The New Arab. Bayyari’s article is not a biographical profile of Abdelki, but rather an effort to move past the “long night” and recognize the artist’s contributions and sacrifices for Syria’s struggle for freedom, both before and after the 2011 Revolution. He states, "It is natural that no tribute will be held for him in his country during that long night; I believe it is essential to organize a significant celebration for him, as freedom has remained a central theme in many of his works, sculptures, paintings, and graphics." This recommendation genuinely deserves attention.

I have been familiar with Youssef Abdelki's artwork since 1995 or 1996, when a mutual friend shared samples of his work with me and connected us by phone. Since then, Al Jadid has featured several of his artworks and published an article about him by Mohammad Ali Atassi** on his return to Damascus from Paris in 2005.

In his article, Bayyari unveils the human side of Abdelki, breaking through his traditionally stoic image. He portrays a man who contrasts with his public persona, rarely seen smiling and consistently projecting an air of sternness. The man behind this "reserved image" seldom allows himself to shed tears. For example, Bayyari notes that Abdelki "did not tear up at times because tears did not obey him." The author frequently correlates stoicism to “stubbornness,” a term he deliberately employs in his article.

Unlike his moderately talkative demeanor in the Al Araby TV documentary interview with Ans Azrac, my recollection of speaking with Abdelki by phone in the late 1990s is that he was reticent and terse, aligning with his reserved image.

In some instances, Bayyari claims, Abdelki attempted to suppress his tears. In others, however, they betrayed him — particularly when his Al Araby interview shifted to the suffering of Syrian mothers whose sons had been detained or killed. These mothers, who had demonstrated and chanted a single four-letter word — “freedom” — embodied the ongoing tragedy of Syria. Overwhelmed by profound sorrow, Abdelki could not continue speaking for a moment as his rugged demeanor and conscience succumbed to the weight of their suffering. His artwork reflects this pain, focusing more on the anguish of these mothers than on the detainees or the martyred victims themselves — scenes I am familiar with as a follower of his Facebook postings.

Abdelki's loyalty to his friends is legendary. One such friend is Abd al-Aziz al-Khair, a Syrian leftist intellectual and prominent opposition figure who has been missing since 2012. Abdelki leaves his phone number on the door of his Damascus studio so that his friend can call him if he is ever freed from Assad's prisons after the regime’s downfall. His friend has not yet returned, but the artist still waits for him with his gentleness.

For those who question the absence of color in Abdelki’s works and the dominance of charcoal, black, and white, the answers lie in the themes he explores. Many of his subjects are reflective, existential, and solemn. As Bayyari notes, Abdelki is renowned for his charcoal drawings, emphasizing the stark contrast of black and white. He does not consider himself a colorist but a painter, perhaps because eliminating color removes distractions and leads to a more introspective and conceptual experience.

When asked whether he has created works about Gaza, he referenced a joint Arab exhibition in Qatar titled “The Sky Above Gaza Imagined,” later renamed “Gaza Diaries.” His contribution depicts a body lying on the ground, bombed from a black sky. A particularly poignant moment in the Al Araby documentary lingers in the minds of those who watched it: “Youssef Abdelki wept obediently. May God not sadden him or bring him any distress.”

*Maen al-Bayari’s essay, “Youssef Abdelki’s Obedient Tears,” was published in Arabic in The New Arab.

**Mohammad Ali Atassi’s essay, “Youssef Abdelki’s Homecoming,” appeared in Al Jadid, Vol. 11, Nos. 50/51, Winter/Spring 2005. To read the full article, click on the link below:

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 113, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE