Lebanon’s Maronite Exception:

Minority Politics Without Authoritarianism

Lebanon's politics have occupied a large part of my life. Reflecting on my past and drawing on refreshed memories of early Lebanese days and the diaspora, I can clearly see that my perspective on Lebanese politics has shifted between idealistic and realistic outlooks.

From Haven to Prison:

The City in the Modern Arab Novel

It was once true that the city was where everyone wanted to be, where those seeking change and connections would flock in hopes of realizing their dreams. Arab cities were the opportune nesting grounds for any kind of cultural activity, the birthplace of famed literary salons, social hubs, and creativity beyond the mind’s eye.

Care Without Spectacle:

Fairouz, Motherhood, and Love Beyond Time

Very little is known of Hali Rahbani, the youngest son of Lebanese singer and icon Fairouz and the late Lebanese composer and musician Assi Rahbani. Hali passed away at the age of 68 on January 8, 2026, months after the death of his elder brother, the composer Ziad Rahbani.

The Algeria Camus Could Not See:

The Paradox of Humanism in a Colonial Landscape

The Algerian Revolution and Albert Camus' legacy persist in Arab writings, primarily among extreme nationalists and moderate humanists. Algerian nationalists highlight Camus' silence during the Algerian War of Independence and his refusal to endorse anti-colonial struggle, which led critics to interpret his attitudes as constrained by his universalism. The discourse has featured the moderates or revisionists.

The Port That Made a City:

Inside a Landmark Exhibition Tracing Beirut’s Evolution and Its Unresolved Trauma

In the five years since a devastating explosion rocked Beirut Port, the Lebanese people and victims of the tragedy have yet to secure long-awaited answers.

The Ghosts of Syria’s History:

Between Erasing and Repeating the Past

I have been closely examining the pressing controversy surrounding the al-Sharaa HTS government's decisions to politicize Syrian history, alter the national holiday calendar, and manipulate the collective memory of the Syrian people. The government has motioned to remove holidays commemorating the October War of 1973, March 8 Revolution Day, Teachers’ Day, and Martyrs’ Day based on the HTS's aim to distance the newly formed state from Hafez al-Assad's legacy.

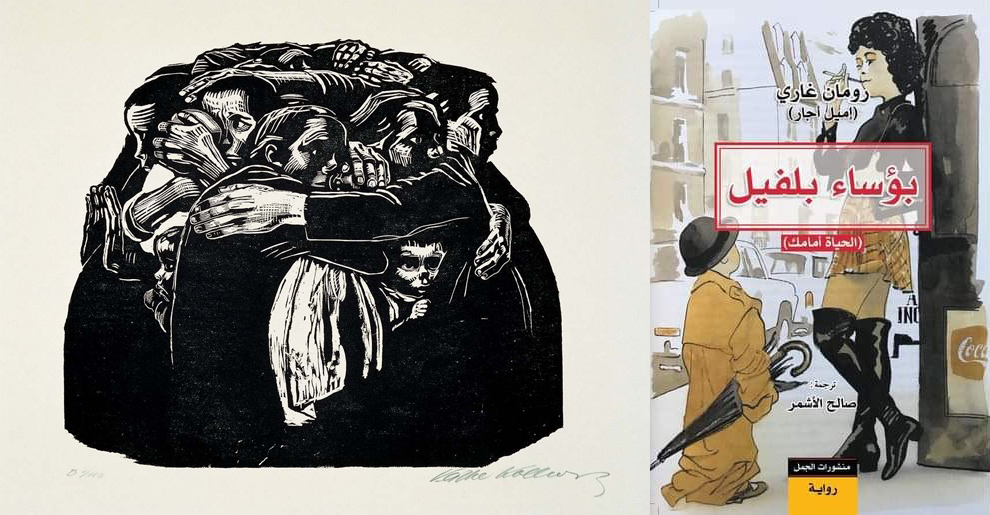

A French Novel, an Algerian Soul:

Reading ‘The Life Before Us’ Across Borders

When an unknown author claimed the Prix Goncourt in 1975 with his novel “The Life Before Us” (La Vie Devant Soi in French), news media scrambled to unravel the mystery behind the bestselling book and its writer.