Arab and Mideast Dictators Mock the U.S. With Their ‘Pity’ in Wake of Capitol Riot

As insurrectionists, white supremacists, and rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol, the world watched with rapt attention. Some watched in horror while others relished one of the darkest days in American history. World leaders were quick to comment on the turmoil, from America’s allies who condemn the actions of President Trump’s supporters, to authoritarian leaders who veiled their celebrations with consolatory statements, predicting that “America would be consumed with turmoil for the next four years,” according to an ISIS publication as cited by Robin Wright of the New Yorker.

That the Capitol riots marked a distinct turn in the world’s perception of American democracy remains debatable. However, the denouncements of the turmoil by many Mideast countries carry an ironic aftertaste. President Erdogan of Turkey — whose government arrests political dissidents and journalists — criticized the storming of the U.S. Capitol by pro-Trump demonstrators, referring to it as a “disgrace for democracy,” and urged the United States to “maintain restraint and prudence.” Mustafa Sentop, Speaker of the Turkish Grand National Assembly, tweeted: “We follow the events in the USA with concern and invite the parties to calmness. We believe that problems will always be solved within law and democracy. As Turkey, we have always been in favor of the law and democracy and we recommend it to everyone,” a cynical assertion that mirrors statements the U.S. traditionally directs towards authoritarian regimes.

The Iranian leadership shared similarly hypocritical reactions to the unrest in Washington, questioning American democracy. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said in a televised address that Washington “really showed how floppy and weak the Western democracy is, and how weak its foundations are.” On a global scale, the Capitol riots appeared to be a forfeiture of the U.S.’ claim to be a political model or world leader in Wright's words. Some of the most ironic statements came from Iran’s closest ally, Syed Hassan Nasrallah, the head of Hezbollah, who said in a speech that the Capitol attack exposed real American democracy and the true nature of the U.S., rooted in “conflict and violence.”

Ironically, one of those lecturing the U.S. on democracy is former Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Malki, considered one of the most corrupt recent Iraqi politicians (and the person in charge of the country when ISIS overran Mosul in 2014). One of Maliki’s memorable statements: “We pride ourselves in being more democratic than the U.S., proud that our democracy is superior to the Americans. The age of American democracy and culture is crumbling.” Abd al-Bari Atwan, a Palestinian journalist and the former editor of Al Quds Al Arabi, commented that the political divisions in the U.S. are like the divisions in the USSR that preceded the collapse of the Soviet Union. “The United States’ collapse is imminent,” he predicted.

Atwan’s predictions match scores of Lebanese “rejectionist” voices who crowd Lebanese screens, social and print media, all taking part in a chorus full of lament and sorrow about American democracy. Meanwhile, they celebrate the virtues of authoritarian regimes and terrorist organizations who actively demolish any basis of democracy in their own country, physically and constitutionally.

(On the left, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, photographed by AP/PTI. On the right, former Iraq prime minister Nouri al-Maliki, photographed by Hadi Mizban for Reuters.)

Covid Claims Third Son of Pioneering Family of Lebanon’s Golden Age of Music

Renowned Lebanese composer and lyricist Elias Rahbani, the youngest of the pioneering Rahbani brothers – who marked the golden age of music and culture in Lebanon – died on Monday at 83 from COVID-19 complications. He was well-known for composing music for prominent performers in the Arab world, including the Lebanese diva Fairouz, the wife of his brother Assi Rahbani.

Born in the town of Antelias north of Beirut, Elias Rahbani was the youngest among his brothers, Mansour and Assi Rahbani. Each played prominent roles in Lebanon’s music scene before the outbreak of the civil war in the 1970s. Elias composed hundreds of songs for singers, like the late Wadih al-Safi and Sabah, and also composed for theater and films. According to the Middle East Eye, he had composed over 2,500 songs. With a career spanning almost six decades, he distinguished himself through his mixture of modern styles and Middle Eastern and Western idioms, diverging from his older brothers' folkloric and traditional approaches. He won a slew of awards, including the Athenes Festival Award for his song “La Guerre Est Finie” and the Youth Award for Classical Music in 1964. He also held pioneering roles as a judge in talent shows in Lebanon and the Arab world, namely the Arab singing competition show Super Star and later seasons of the show Star Academy.

Many Arab artists and politicians eulogized Elias Rahbani after his passing on Monday. Lebanese pop star Elissa honored him on Twitter: “An honest, loving, and creative artist in every sense of the word, and a person who would never exist again with his instincts, talents and eternal deeds...May God have mercy and all condolences to your generous family.” Singer Carole Samaha said, “He took with him the most beautiful musical era in the history of the Lebanese song...Your deeds are immortal in memory and conscience.” Rahbani leaves behind his wife, Nina Maria Khalil, and three children, Ghassan, Jad, and Elham.

(A web-based image of Elias Rahbani.)

FICTION IN FORTHCOMING AL JADID, VOL. 24, NO. 79, 2020Fatherland: Miss Fatima Hussein

A story of family, love, and grief, Hanna Saadah’s “Fatherland: Miss Fatima Hussein” touches on the painful impact of war on those in diaspora. Doctor Salem Hawi grew up in Tripoli, Lebanon, attending the American Evangelical School, where he studied under the charming Miss Fatima Hussein. After becoming a doctor, he leaves for America to specialize. However, he finds himself separated from home and family, forced to watch from afar as Lebanon is consumed by civil war and later return to a torn country that considers him a foreigner. After the death of his brother, he recalls Miss Fatima Hussein’s words: “When you are sad, if you cannot find words that assuage your loss, you may not be able to get over your grief. Be creative in expressing your emotions and make use of literature; it is the balsam of broken hearts.” And so he puts pen to paper and begins to write a poem dedicated to his country, his brother, love, and loss: Fatherland. The theme that sutures the story's quilt together is the young man's unremitting love to his beautiful, aging, lady teacher.

Hanna Saadah’s “Fatherland: Miss Fatima Hussein” will appear in the forthcoming issue of Al Jadid, Vol. 24, No. 79, 2020.

(Undated photograph of the American Evangelical School in Tripoli.)

BOOK REVIEWS IN FORTHCOMING AL JADID, VOL. 24, NO. 79, 2020

Editors Rita Stephan and Mounira M. Charrad’s recent book, “Women Rising: In and Beyond the Arab Spring” (NYU Press, 2020) compiles 40 essays regarding female activism throughout the Arab world. The book is divided into four sections. The first, “What They Fight For,” explores various efforts across the Arab world, from activism on Palestinian LGBTQ rights, including men in the fight against domestic violence in Lebanon, raising awareness of pedophilia in Morocco, and the prominent role of women in the Arab Spring in Yemen. One essay also documents two non-violent Syrian resistance campaigns in 2012, “Stop the Killing'' and “Brides of Freedom.” The second section, “What They Believe In,” explores the changing language in the Tunisian constitution as well as resistance to sectarianism in Iraq, while the third section, “How They Express Agency,” explores the role of cyberspace in transnational political activism. The last section, “How They Organize,” highlights women working in education, government, and religious groups to “change consciousness and help to avoid violence.” In her foreword, Suad Joseph describes “Women Rising '' as a “volume of hope grounded in history and in the lived present '' and this collection verifies this hope by breaking the silence and celebrating reform around gender issues.

“Women Rising: In and Beyond the Arab Spring,” reviewed by Lynne Rogers, is scheduled to appear in the forthcoming Al Jadid, Vol. 24, No. 79, 2020.

BOOK REVIEWS IN FORTHCOMING AL JADID, VOL. 24, NO. 79, 2020

Ideology Trumps the Transnational Arab Artist

In “Interrogating Secularism: Race and Religion in Arab Transnational Art and Literature” (Syracuse University Press, 2019), Danielle Haque examines how certain transnational Arab writers and artists (with one foot in the West and another in an Arab country) have challenged the Western secular space and sought to transform it. Haque’s analysis includes “a number of frameworks for understanding the works in this book, including postcolonial and transnational theories, and Arab American, Muslim American, and Arab anglophone studies.”

In her review of “Interrogating Secularism,” Pamela Nice sees such breadth of theoretical perspectives as jeopardizing the focus of the book, while obscuring the artistic works themselves. Though an interesting variety of works are explored, from novels to art installations, Haque at times makes claims about Western – and in particular, US – secularism that are too facile, thus undermining the strength of her argument.

Nice notes that the best chapters of “Interrogating Secularism” are those in which Haque displays her interpretive talent with less recourse to theorizing. Her analyses of Mohja Kahf’s “The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf” and Rabih Alameddine’s “Koolaids” are “excellent, as she foregrounds the creators and uses a lighter touch when making her ideological claims…[Here], the lack of jargon and theory makes Haque’s thesis much clearer. She lets the works do more of the talking.”

Subscribing to Al Jadid Digital ($15.95) keeps you abreast of our unparalleled coverage of Arab culture and arts. This subscription ensures free digital access to over 15 years of our archive. To subscribe, click on the link below.

Rehabilitation or Reconstruction: Will a Resurrected Beirut Restore Its Architectural and Social Fabric?

The debate over approaches to reconstruction has preoccupied some Lebanese architects and social scientists, especially in the destruction wrought by the 1975 Lebanese Civil War and the more recent Beirut Port explosion. As Lebanon plans for the restoration of Beirut, Lebanese architect, urban planner, and president of the Federation of Engineers and Architects Jad Tabet has been outspoken on prospective plans and policies for the reconstruction and the “rehabilitation” of large parts of the capital. His views on the city’s rebuilding reflect his earlier positions on rebuilding downtown Beirut in the 1990s, when his unceasing concern was preserving the social fabric of the city, advocating for “rehabilitation” rather than reconstruction. He remains guided by the same approach as he addresses the currently debated rebuilding policies of the city after the port explosion. These earlier ideas emerged in his 1998 article, “Arab Architectural Heritage between Mirrors and Idols: Looking Within and Beyond the Tradition-Modernity Debate,” among others.

According to Tabet, we should not treat heritage as a “stagnant” or “mummified” concept, but as a dynamic entity that changes with the environment. He speaks against heritage as defined by historicism and cautions against preserving heritage as a reaction against modernity. Tabet recalls two major architects whose schools contributed to Arab architectural thought: the late Egyptian architect Hassan Fathi and the late Iraqi architect Rifat al-Chadirji. Fathi (1900-1989) was an anti-modernist who believed Arab cultural architecture suffered from Westernization. He maintained that modernity is not always good or better. While Fathi and Tabet differ on the relationship between tradition and modernity, Tabet links the decay in Arab architectural heritage to the Arab world’s “inability to cope with imported Western modernism.” Chadirji (1926-2020) stressed the importance of an architecture consistent with the needs of the present and was against the reflexive reproduction of heritage buildings. Like Chadirji, Tabet did not view modernity and tradition as antithetical concepts.

Above all, Tabet speaks against architecture guided by nostalgia and a longing for a lost heritage, especially in Beirut, a “city with no memory.” Thus he is against rebuilding the damaged grain silos just to restore a “lost memory” of a bygone time, but to allow them to stand as a testament to the tragedy of August’s port explosion and Beirut’s ability to withstand and recover from its wounds.

“Rehabilitation or Reconstruction: Will a Resurrected Beirut Restore Its Architectural and Social Fabric?” by Elie Chalala and Naomi Pham will appear in the forthcoming issue of Al Jadid (Vol. 24, No. 79, 2020).

(Lebanese President of the Federation of Engineers and Architects Jad Tabet, photographed by Greg Demraque.)

The Arab-Israeli Conflict: How the American Left Grabbed the Third Rail of American Politics

The Arab-Israeli conflict has long been a divisive issue in the left lane of American politics. Bitter disagreements came to the fore, especially during periods of armed conflict and subsequent occupation, such as the wars of 1967 and 1973, and Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. The author of a new book on this subject claims these divisions significantly weakened and perhaps even contributed to the demise of the American Left during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

The landscape now, however, is noticeably different. During the presidential campaign of 2016, Bernie Sanders violated a tradition long-observed by almost all serious democratic and republican primary contenders, when he snubbed the annual conference of American Israeli Political Action Committee (AIPAC). Only a few years ago, Sanders' criticism of Israel was unthinkable.

In his most recent book, ‘The Movement and the Middle East: How the Arab-Israeli Conflict Divided the American Left’ (Stanford University Press, 2019), Professor Michael R. Fischbach provides some clues for those who “cannot help but marvel at how criticism of the Israeli government has become so commonplace in recent years,” writes Michael Teague in his forthcoming review of the book. According to Fischbach, “Where progressive Americans stand on these issues today stems from events of the past,” namely, the past of the American left that he expertly reconstructs, and history that he contextualizes for the reader in this short but impactful work. The author also claims that the division caused by the Arab-Israeli conflict has weakened the “white left” and contributed to its eventual demise.

He identifies two main strands of the left. The first comprised the socialists and anti-imperialists who considered the PLO’s armed struggle against Israel as a part of this movement. The second represented those who believed Israel was a socialist state living in precarious conditions and thus deserving of exception from the “imperialist” epithet.

The debate between these two sides has been contentious, leading leftist supporters of Israel to diagnose any opposition or criticism as anti-Semitic.

Interestingly, some neo-conservative operatives, now known for their support of the Iraq war, originally defected from the left over Israel. Their departure, and the rancorous debates, as well as the vicious arguments between anti-imperialist and Israeli-exceptionalists in the wake of the Six-Day War, brought the subject of Palestinian dispossession to a much wider audience than ever before, concludes Teague.

Michael Teague’s forthcoming review of “The Movement and the Middle East: How the Arab-Israeli Conflict Divided the American Left,” is scheduled to appear in Al Jadid, Vol. 24, No. 79, 2020.

(Photograph of Bernie Sanders courtesy of Vox Media.)

Documentary Reveals Constant Surveillance of Arab Americans

Combining the personal with the political, young filmmaker and journalist Assia Boundaoui uncovers decades of FBI surveillance of her Arab American neighborhood on the outskirts of Chicago. Her documentary, “The Feeling of Being Watched” (Women Make Movies, 2018), follows Assia as she digs into the history of FBI involvement in her community, dating as far back as 1997 and continuing to the present. Constant surveillance and a perpetual unsafe feeling, “like someone is invading your life” haunt the residents of her hometown, where many still harbor lingering fears after their neighborhood was ‘visited’ — a euphemism for FBI questioning — several years before. Distrust and racism run rampant, and Assia turns to the Freedom of Information Act to petition for the release of the FBI reports on her community.

“The Feeling of Being Watched,” reviewed by Lynne Rogers, is scheduled to appear in the forthcoming Al Jadid, Vol. 24, No. 79, 2020.

(Stills from the film, courtesy of Women Make Movies.)

FILM REVIEWS IN FORTHCOMING AL JADID, VOL. 24, NO. 79, 2020

Women Still Standing in the Documentary ‘I Am the Revolution’

Capturing the everyday lives of women devoted to activism, Benedetta Argentieri’s documentary “I Am the Revolution” (Women Make Movies, 2018) gives an up-close and personal look into the grassroots activism in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq after the Arab Spring. Argentieri tells the stories of several women, from Selay Ghaffar, the daughter of a freedom fighter who grew up as a refugee in Iran and Pakistan and risks her safety meeting victims throughout Afghanistan, to Yanar Mohammed, who fights for women’s rights in Iraq, and Rojda Felat, a Syrian-Kurdish commander who played a leading role against ISIS in Raqqa. Some stories glimpse into the front lines as viewers meet Syrian women fighters and mourn alongside them as they bury their comrades. In the words of the reviewer, ‘“I Am the Revolution” not only provides an in-depth view into the lives of these female crusaders, but their individual and inspiring bravery provide a hopeful model for both the Western and non-Western world.”

“I Am the Revolution,” reviewed by Lynne Rogers, is scheduled to appear in the forthcoming Al Jadid, Vol. 24, No. 79, 2020.

(Film still of protestors in “I Am the Revolution,” courtesy of Women Make Movies.)

On Poetry and Childhood

By Muayyad al-Rawi

Poetry often defies definition. On the one hand, poetry invariably exists in a self-referential crisis it is always trying to overcome, while on the other it holds up a mirror to humanity’s own crises across the ages. Perhaps this complexity is due in part to the fact that, in my view, poetry, and art generally, is opposed to logic. Our everyday world, however, mostly runs on the power of logic and reason, which form a system controlling modern life that distances us from poetry.

Poetry often defies definition. On the one hand, poetry invariably exists in a self-referential crisis it is always trying to overcome, while on the other it holds up a mirror to humanity’s own crises across the ages. Perhaps this complexity is due in part to the fact that, in my view, poetry, and art generally, is opposed to logic. Our everyday world, however, mostly runs on the power of logic and reason, which form a system controlling modern life that distances us from poetry.

None of the ancient myths or arts bequeathed to us from our forebears were governed by the kind of logic that governs us today. This is why they can still inspire awe and introspection; they are, to a great extent, poetic, as we see best in the great epics of literature.

By logic I mean here the whole of human knowledge that is passed down from one generation to the next, the prerequisite conditions and laws that have accumulated over time to govern people, setting the course of their lives and the trajectory of their desires in a pragmatic direction.

We first learn this logic, this way of living in the modern world, from childhood, through the institution of the family. Then in schools and universities, we are bombarded with all sorts of instruction and preparation in order to instill in us a discipline to resist any “passion,” imaginative expression, or risky intellectual endeavor that could enable us to rediscover the world many times over.

Children are born poets. They see the world differently from socialized adults. We recognize the visible, while children see the liminal spaces of the geography we have mapped. So too, their sense of time is not limited to past, present, and future, nor hours, days and years. Children are bathed in the wonder of exploration and the delight of adventure.

Dreams, too, are like children, refusing to bow to logic. Perhaps they serve as an escape from the confinement of logic, a return to childhood, to the wellspring of life and a re-imagining of this world.

I believe that a crucial part of any poet’s enterprise must be to escape the collective identity into which we have been domesticated, and to depart from the heavy-handed hierarchy of institutions on which this identity rests. The poet’s mission is to discover a deep, intrinsic sense of self outside the social structure. Such an undertaking is necessarily difficult, as it casts the poet out of “life” as we know it. But in return, the poet draws near to poetry. It is an enterprise that, through reflection and solitude, brings the poet back to life, and into dialogue with the nature of things outside their former boundaries. It accords the poet a language freed from its pragmatic function.

(Poet Muayyad al-Rawi "On Poetry and Childhood" on the fifth anniversary of his passing, October 8, 2015, Berlin.)

BOOK REVIEWS IN FORTHCOMING AL JADID, VOL. 24, NO. 79, 2020

Brothers Take Two Paths to Exile in Jordan Ritter Conn’s ‘The Road from Raqqa’

Poetry often defies definition. On the one hand, poetry invariably exists in a self-referential crisis it is always trying to overcome, while on the other it holds up a mirror to humanity’s own crises across the ages. Perhaps this complexity is due in part to the fact that, in my view, poetry, and art generally, is opposed to logic. Our everyday world, however, mostly runs on the power of logic and reason, which form a system controlling modern life that distances us from poetry.

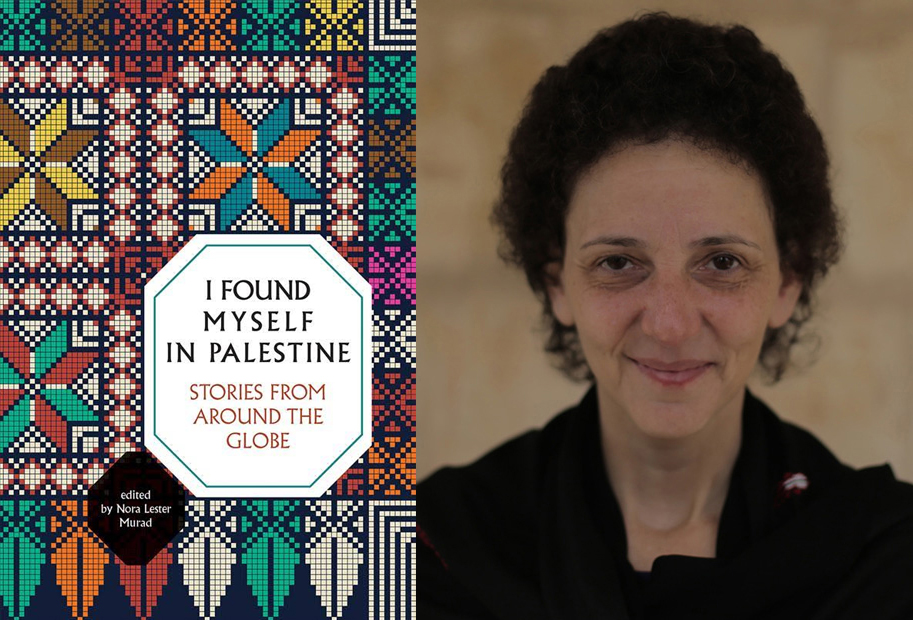

Poetry often defies definition. On the one hand, poetry invariably exists in a self-referential crisis it is always trying to overcome, while on the other it holds up a mirror to humanity’s own crises across the ages. Perhaps this complexity is due in part to the fact that, in my view, poetry, and art generally, is opposed to logic. Our everyday world, however, mostly runs on the power of logic and reason, which form a system controlling modern life that distances us from poetry. Editor Nora Lester Murad, an ajnabeeya (foreigner) herself, presents a collection of essays written by non-Palestinians in “I Found Myself in Palestine: Stories of Love and Renewal from Around the Globe” (Olive Branch Press, 2020). From the story of Steve, who marries and starts a family with a Muslim woman from Ramallah and building the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund, to Japanese activist and Professor Saul Jihad Takahashi, who finds faith in Islam, these essays tell the stories of people who find hope, love, and solidarity under occupation, as well as detail domestic life in Palestine from “the outsider on the inside,” in the words of the reviewer.

Editor Nora Lester Murad, an ajnabeeya (foreigner) herself, presents a collection of essays written by non-Palestinians in “I Found Myself in Palestine: Stories of Love and Renewal from Around the Globe” (Olive Branch Press, 2020). From the story of Steve, who marries and starts a family with a Muslim woman from Ramallah and building the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund, to Japanese activist and Professor Saul Jihad Takahashi, who finds faith in Islam, these essays tell the stories of people who find hope, love, and solidarity under occupation, as well as detail domestic life in Palestine from “the outsider on the inside,” in the words of the reviewer. Hundreds of books and thousands of articles will be written about Beirut and the explosion at the Port. The city occupies a special place in my heart that transcends patriotic sentiment. It is composed of simple, personal, emotional, and unfading memories. Since August 4th, I have been fixated on news from Beirut, jotting down any notes that evoke nostalgic memories of a bygone era. For more than a decade, Beirut has been struggling to heal old emotional wounds, starting with the assassination of the former prime minister and a group of intellectuals, journalists, and politicians that followed. None of the assassins ever met justice. Mindful of the Special Tribunal verdict in the trial for the 2005 bombing that killed former PM Rafik Hariri, which is expected on August 18th, and the uncertainty over the assassination of others, Lebanese journalist Ghassan Charbel wrote: "Covering up the assassinations in the capital is one thing while covering up the assassination of a capital is a different matter.” Close observers of Lebanese politics cannot miss the symbolism of Charbel’s statement. While identifying those who assassinated the leaders of the Cedar Revolution remains difficult, identifying those who destroyed Beirut will not be.

Hundreds of books and thousands of articles will be written about Beirut and the explosion at the Port. The city occupies a special place in my heart that transcends patriotic sentiment. It is composed of simple, personal, emotional, and unfading memories. Since August 4th, I have been fixated on news from Beirut, jotting down any notes that evoke nostalgic memories of a bygone era. For more than a decade, Beirut has been struggling to heal old emotional wounds, starting with the assassination of the former prime minister and a group of intellectuals, journalists, and politicians that followed. None of the assassins ever met justice. Mindful of the Special Tribunal verdict in the trial for the 2005 bombing that killed former PM Rafik Hariri, which is expected on August 18th, and the uncertainty over the assassination of others, Lebanese journalist Ghassan Charbel wrote: "Covering up the assassinations in the capital is one thing while covering up the assassination of a capital is a different matter.” Close observers of Lebanese politics cannot miss the symbolism of Charbel’s statement. While identifying those who assassinated the leaders of the Cedar Revolution remains difficult, identifying those who destroyed Beirut will not be.