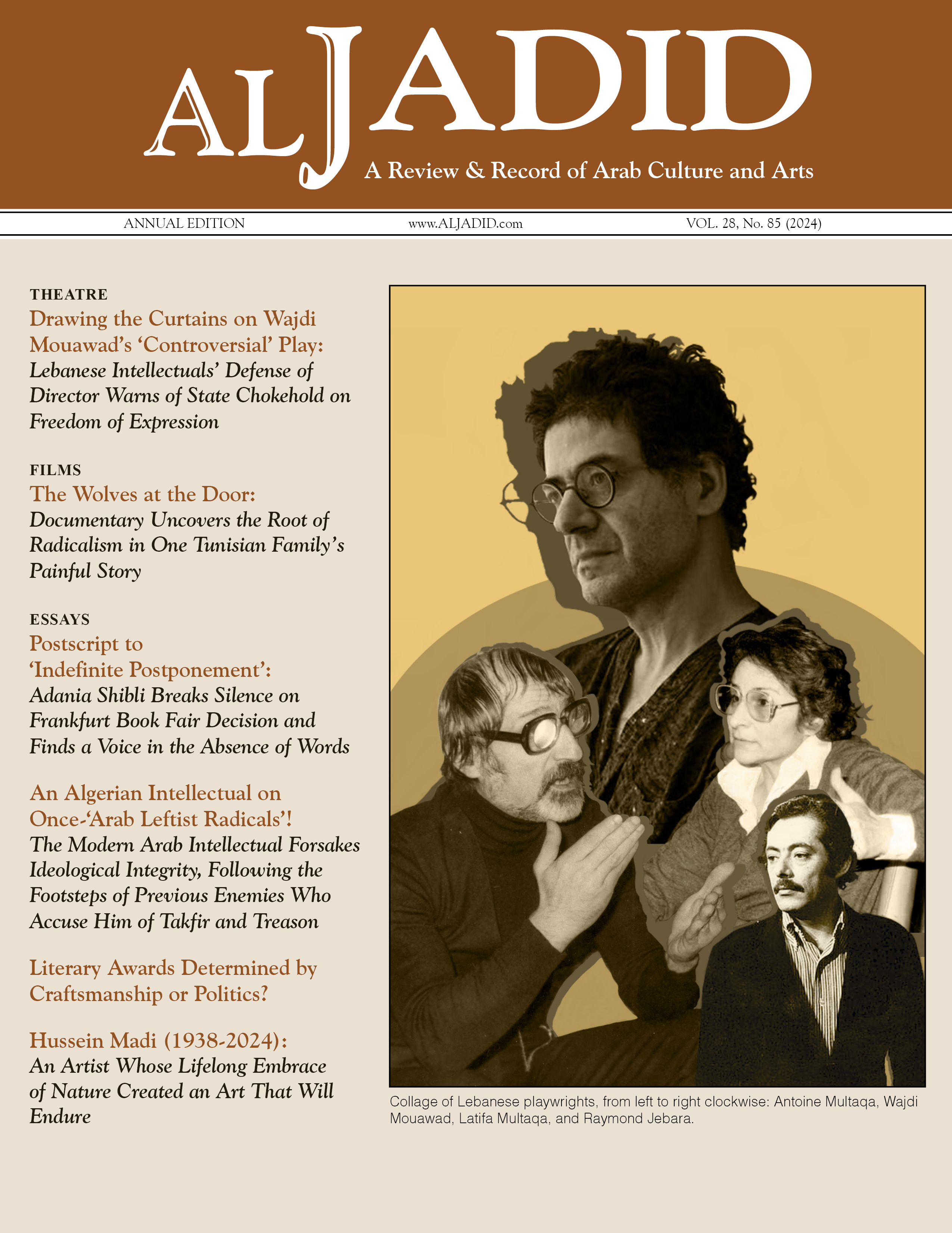

The State of Arab Journalism: Emile Menhem’s Dynamic Blend of Text and Visual Aesthetics Modernizes the Arab Newsroom

Emile Menhem: Invigorating Arab Journalism Through Graphic Design

By Lara Balaa

Khatt Books, 2019

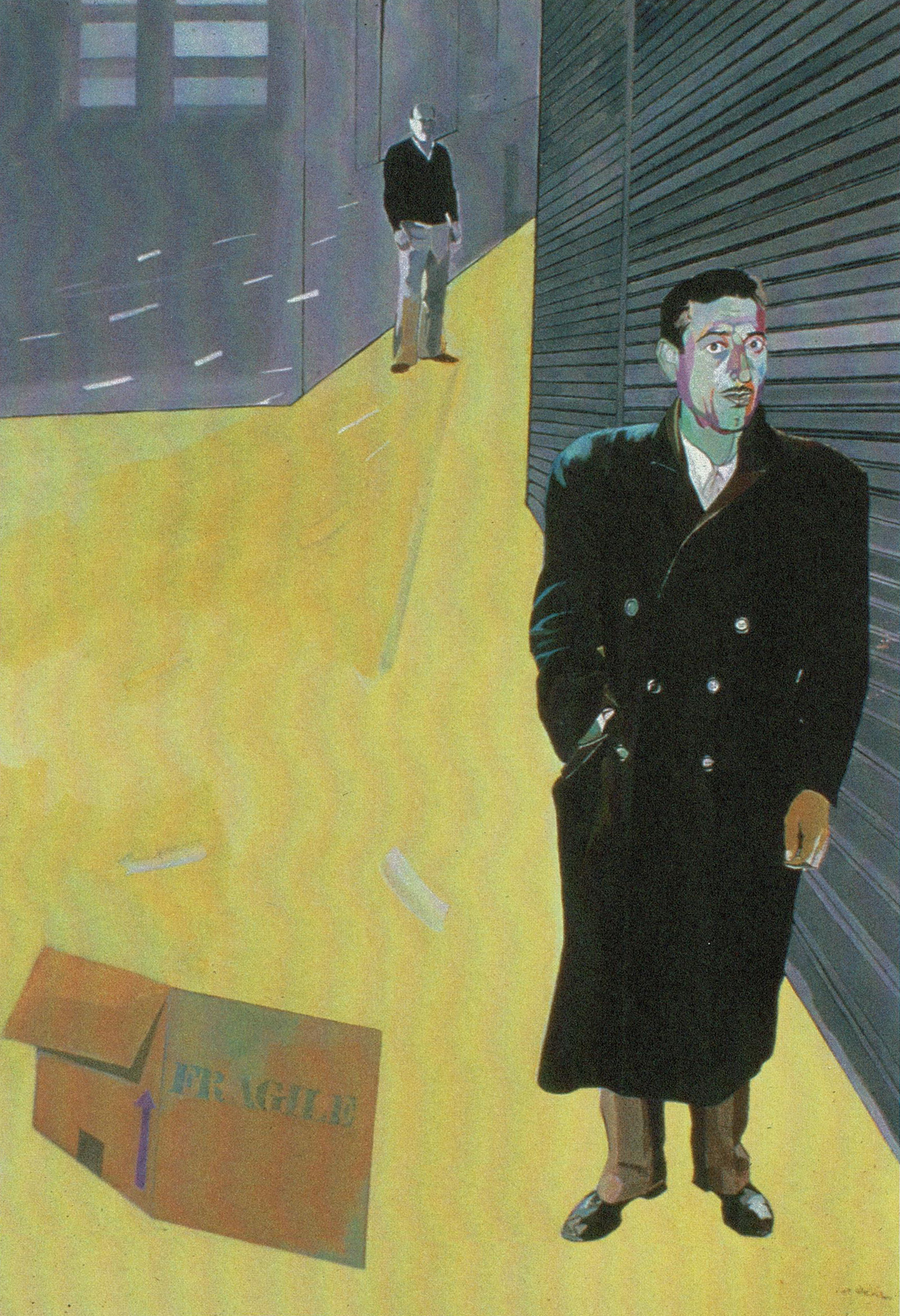

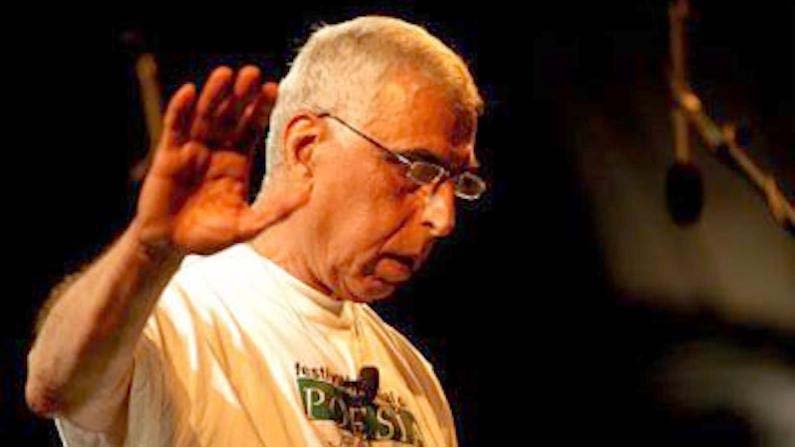

Important, Sometimes Controversial Iraqi Poet Saadi Youssef (1934 - 2021) Requests a ‘Funeral Without Mourners’

The legendary and controversial Iraqi poet Saadi Youssef died at 87 in his Harefield home outside of London on June 12 from lung cancer. The poet, whose multitude of works encompassed poetry, prose, literary criticism, translation, and memoir, leaves decades’ worth of work penned in exile and translated into several languages, among them English, French, German, and Italian.