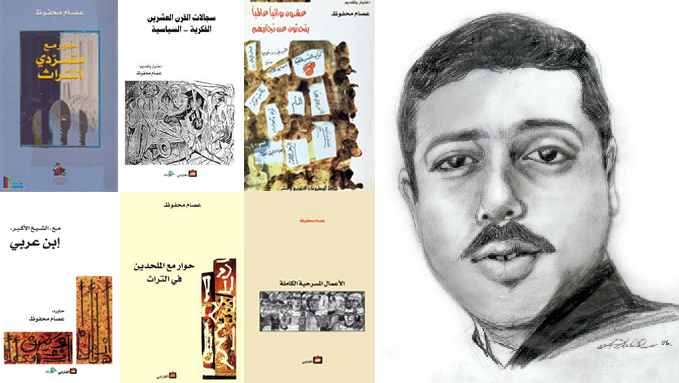

Multiple Pressures From State Repression, Fundamentalist Retribution, Cultural Critiques and Competition From Global Media Choking Off The Voice Of The Arab Intellectual

Many definitions of Arab intellectuals are rooted in the idealistic tradition that glorifies them as guardians of values and ethics, as figures closer to “angels” and “faqihs,” who stand above politics and power struggles and enjoy a monopoly over the authority of knowledge. These notions reflect social illusions and popular perceptions of the time when intellectuals were considered part of a sacred class.

The Wonders of a Village Childhood

Stories My Father Told Me: Memories of a Childhood in Syria and Lebanon

By Elia Zughaib and Helen Zughaib

Cune Press, 2020

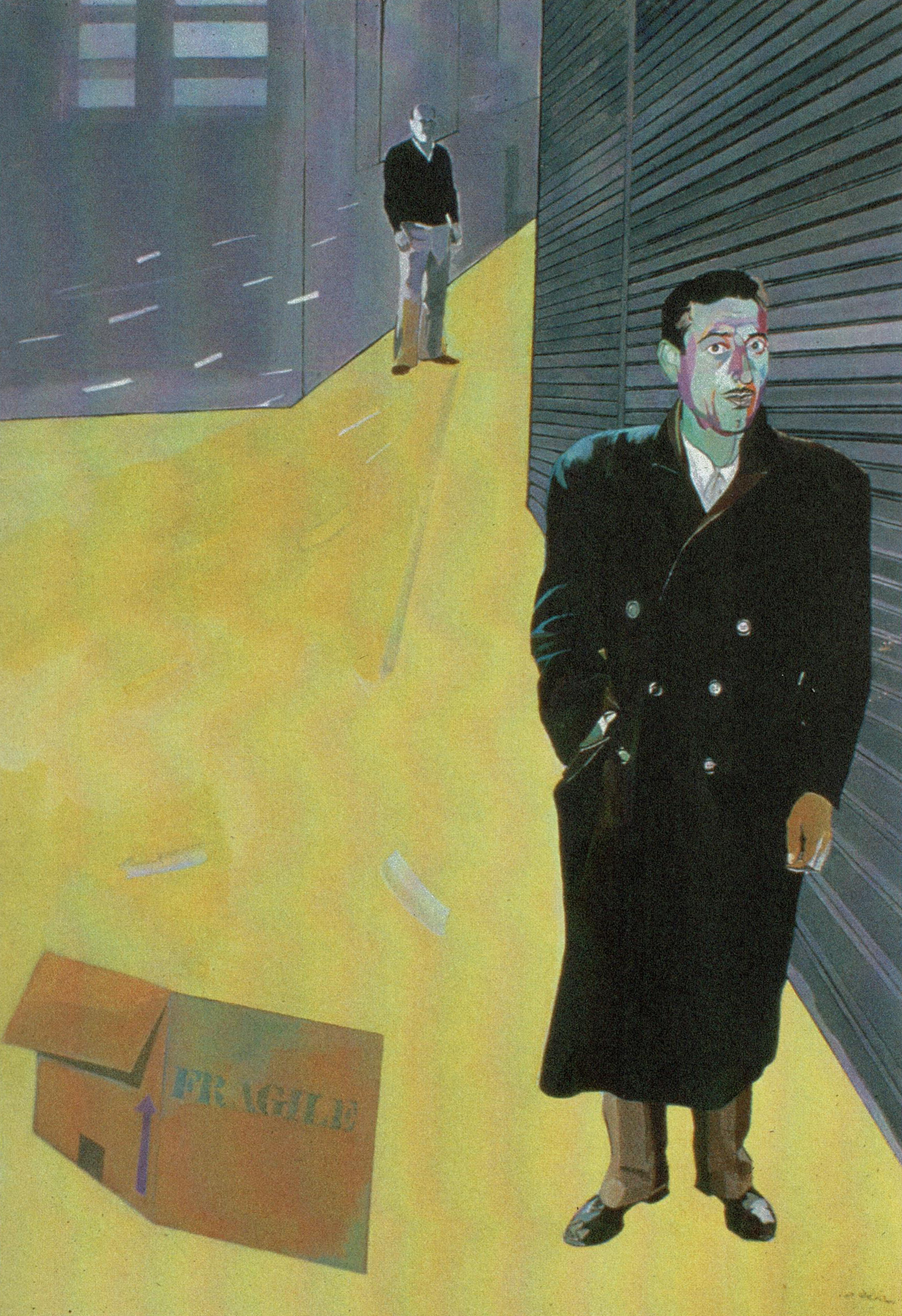

“Stories My Father Told Me: Memories of a Childhood in Syria and Lebanon” is a delightful collection of short one-page stories told to Elia Zughaib by his father, accompanied by paintings by his daughter, Helen Zughaib.

A Book Fair Writes an Old Story: How a Poster — And Regional Politics — Sank Effort to Invigorate Lebanon’s Publishing Industry

Book publishers, journalists, authors, and cultural activists received a large blow earlier this month. The anticipated return of the Beirut International and Arab Book Fair was met with disappointment and anger as violence broke out over Hezbollah’s presence through some publishing houses, which many argued overshadowed the spirit of the event. For over half a century, the book fair has held a celebrated place in Lebanon’s culture.

Book Examines Lasting Legacy of Assassinated Cartoonist, Whose Work Drew on Experience of War and Exile

A beloved artist in and beyond the Arab world, Palestinian political cartoonist and caricaturist Naji al-Ali's influence continues after 30 years after his death by assassination. Boualem Ramadani in the New Arab Diffah Supplement recently discovered a French book dedicated to al-Ali’s work, the first of its kind in France. Though published only in French, the book — "Le Livre de Handala" by Sivan Halevy and Muhammad al-Asaad, published by Scribest — includes important input from Naji al-Ali's eldest son, Khaled.

Beating Up the Already Battered: Modern Arab Media’s Role in Bullying and Harassment

Harming, intimidating, or mocking the vulnerable are familiar behaviors; some have witnessed the abuse from afar, while others have experienced it. We used to think of bullying as something that children do in the schoolyard, and ideally something they learn to stop after reflection and normal maturation. But beyond the playground, bullying and harassment serve as standard practice in fields like modern media.

Plot Twist Ties up Distribution of Controversial Arab “Life Smuggling” Film

Egyptian filmmaker Mohamed Diab’s 2019 “Amira” faced a storm of social media backlash following accusations that the film belittles the Palestinian struggle. Diab — director of the well-received “Cairo 678” (2010) and “Clash” (2016) — has pulled the film from any future screenings, including Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Film Festival. This decision comes after Jordan’s Royal Film Commission ultimately withdrew “Amira” as its entry as the Oscar’s 2022 Best Foreign Film.