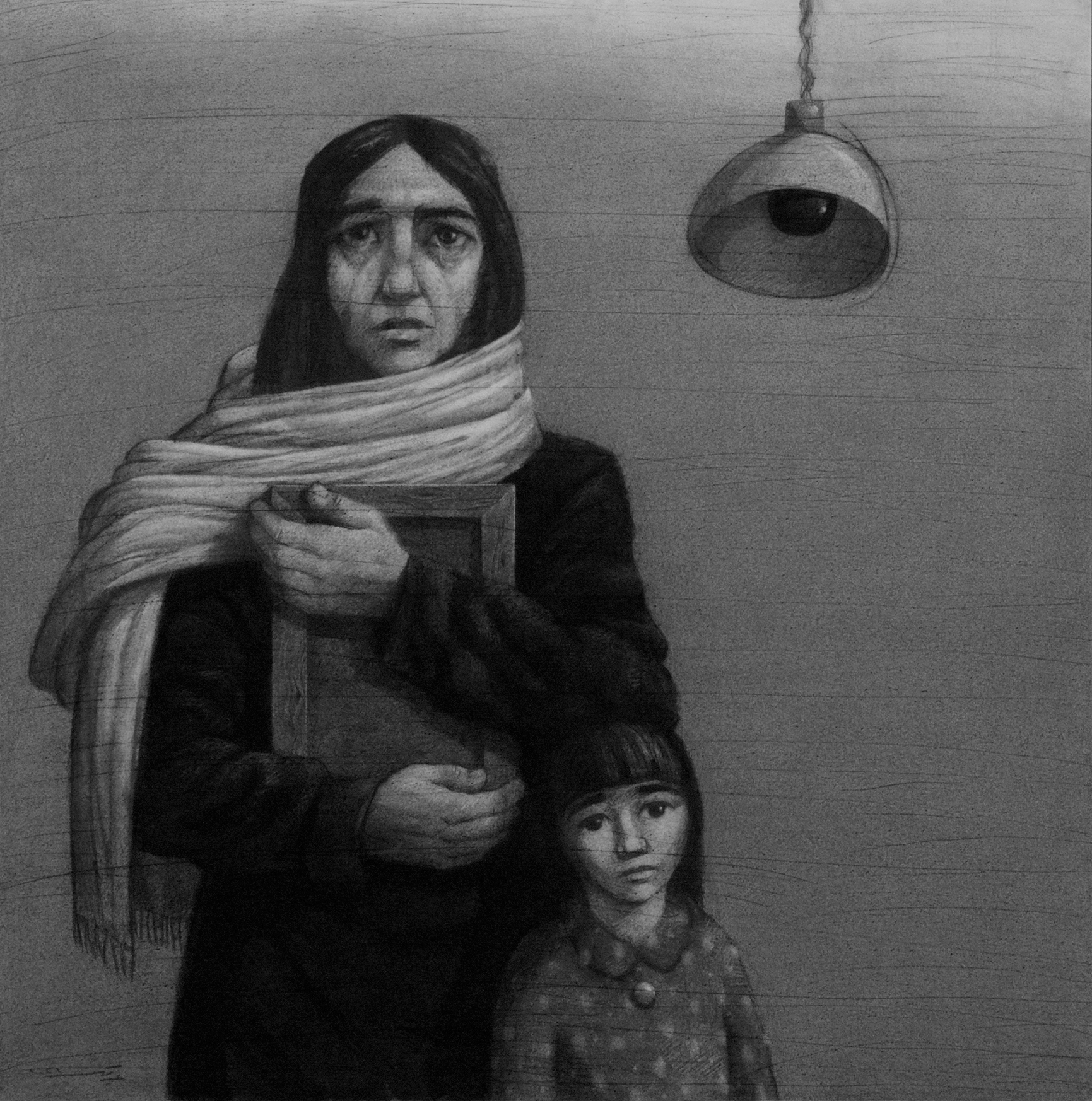

"Syria Untold" by Youssef Abdelki.

A reader may wonder why I am so captivated by prison literature. Personally and professionally, I have had to address this valid question with deep conviction, as it lies at the heart of Middle Eastern and Arab studies. Yet, I find it challenging to offer a concise answer for several reasons. One stems from my doctoral research on Syrian politics, where the themes of prisons and prisoners featured prominently. In addition, I have translated and published numerous articles on this subject in this magazine.

Since the early 1980s, literature about prisons in Syria and Iraq has remained consistently present, with new books and articles continually emerging. Later in my career, I shifted my focus to World War II and developed a strong interest in the works of Primo Levi (1919–1987), a Jewish-Italian partisan, Holocaust survivor, chemist, and writer. His writing further fueled my passion for prison literature, an interest that has stayed with me through graduate school, my academic career, and my role as editor of this magazine. It has allowed me to explore the subject more deeply and consistently.

I set my sights on a clear goal: to elevate the discourse on prisons and prisoners from a routine conversation to a more profound and urgent dialogue. What is at stake is existential. I hope to direct readers’ attention to the issue of incarceration with the same passion that drives me. This involves advocating for a just judicial system, free of injustice, and for a vision of prison life where inmates are treated with dignity, given access to education and vocational training, and supported in reintegrating into society upon release.

Within this context, I was drawn to a recent column by the Syrian writer Ali Safar titled “A Museum for Those Who Take Refuge from Death,”* published in Al Modon. Safar, a Paris-based contributor to Arabic-language publications, draws a powerful and ironic comparison between Syrians and Iraqis who went into hiding to escape Baathist regimes and Anne Frank’s experience in Nazi-occupied Netherlands during World War II.

Safar recounts a 2003 report by The Daily Telegraph about an Iraqi man who refused to join the military during the Iran-Iraq War and hid in a grave-like hole — less than a meter wide — beneath his family's kitchen for over 20 years. He only emerged when he heard the news of Saddam Hussein's overthrow over a radio broadcast. A similar case followed: another Iraqi citizen revealed that he had spent two decades in a basement evading a death sentence for his membership to the then-banned Dawa Party. For further insight into Iraq’s climate of fear under Baathist rule, I recommend Kanan Makiya’s “The Republic of Fear.”

Safar also highlights a Syrian case. Waref Katbi, a content creator in Assad’s Syria, recently reported on Abu Zakour al-Ladhiqani, who, after a single arrest in 2012, decided to hide from regime informants. Instead of fleeing, he built a wall in his house to create a narrow, hidden room. He remained concealed there for 13 years, a silent witness to the horrors, only reemerging when he heard rumors that Bashar al-Assad had fled the country. His reemergence, prompted by hope, mirrors the fragile line between survival and disappearance.

These individuals managed to escape the grasp of Baathist regimes with the help of just one or two people, in sharp contrast with the fate of Anne Frank, the Dutch Jewish girl who hid in a secret annex with her family for nearly two years before they were discovered in 1944 following an anonymous tip and deported to concentration camps. Anne and her sister Margot died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen shortly before the camp’s liberation. Their story, preserved through Anne’s diary, became one of the most widely read accounts of the Holocaust, translated into over 70 languages.

The irony Safar draws is striking: while Anne Frank’s short life is documented and remembered worldwide, the lives of many Syrians and Iraqis who endured similar terror remain undocumented and largely forgotten. None of the three Arab individuals mentioned by Safar wrote diaries. Their stories, with rare exceptions, have not been preserved or widely shared.

Safar introduces a poignant theme: the gamble of survival. Ironically, survival does not guarantee recognition or remembrance. Anne Frank did not survive, but her story did. Others, like Zakour, may survive only to vanish into obscurity or later be arrested and silenced. Safar briefly mentions figures like the Syrian Abdul Aziz al-Khair, a prominent leftist activist abducted in 2012, whose fate remains unknown.

One of the most haunting passages in Safar’s essay describes “the air as a symbol of survival.” He writes:

“In a bloody environment, even the air becomes a reservoir of hope that you will survive for a few more minutes or hours. So much so that when you recall what you experienced, you feel compelled to acknowledge the shifts in the colors of your breath, for they sustained you while hope faded for others and drifted into the unknown.”

This poetic image speaks to the essence of resilience in the face of unspeakable horror.

Safar’s vision extends beyond storytelling to the act of commemoration. He calls for the creation of museums in post-Assad Syria — spaces that would document the crimes committed against the Syrian people, including stories of hiding, imprisonment, and resistance. Inspired by digital activist Amer Matar’s ISIS Prison Museum, which offers virtual exhibits and testimonies, Safar imagines institutions that would preserve Syria’s hidden history and help pursue justice.

For Safar, these proposed museums would not merely be about the past but spaces of witness and resistance. He writes of hidden rooms, caves, and scribbled notes on prison walls — fragments of survival that must not be erased under the pretext of “national reconciliation.” Like Anne Frank’s diary, these remnants are part of our collective memory; preserving them is a moral imperative.

*Ali Safar’s essay, “A Museum for Those Who Take Refuge from Death,” was published in Arabic in Al Modon.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 116, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE