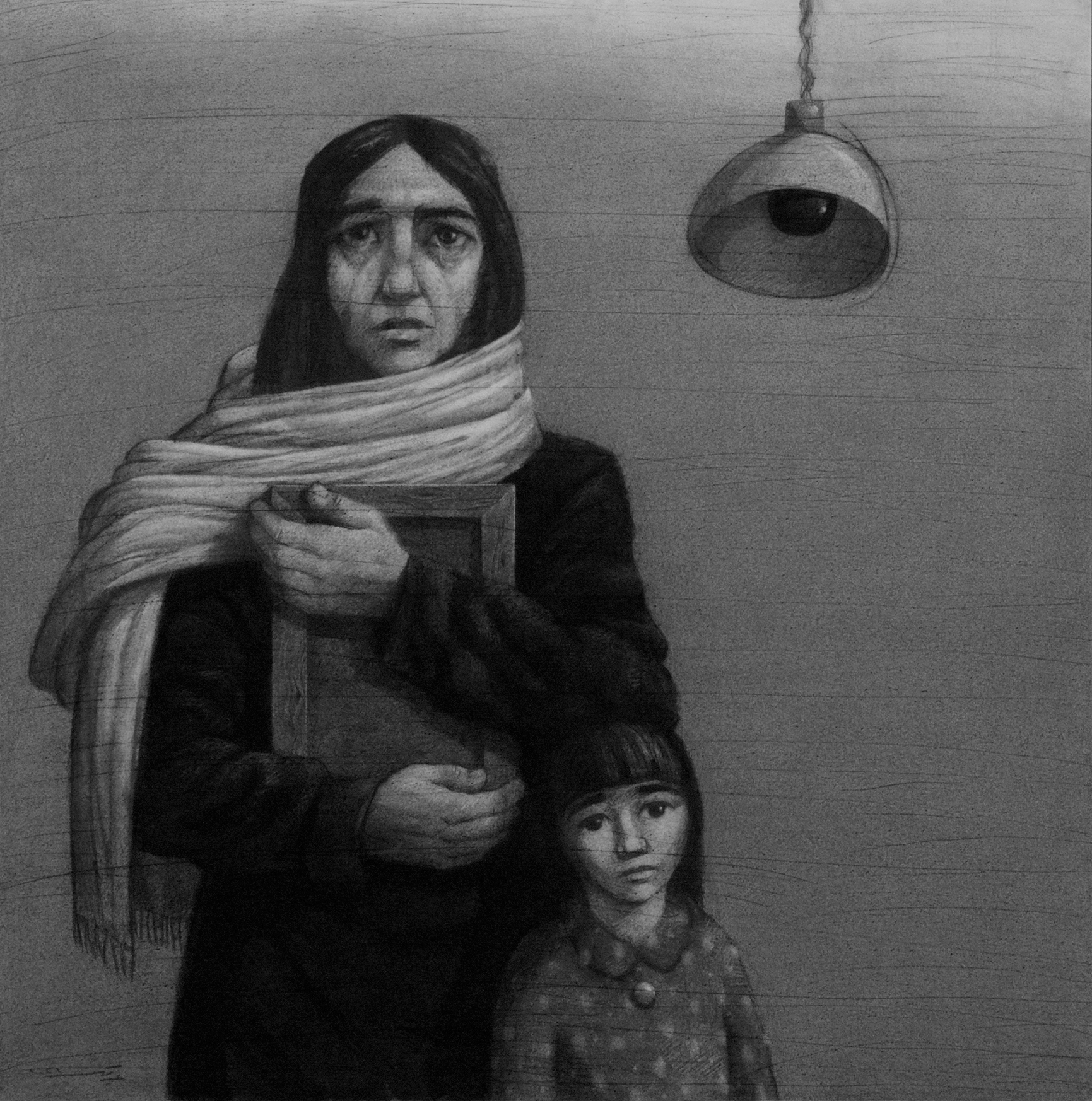

Dismantling the Politicization of the Veil:

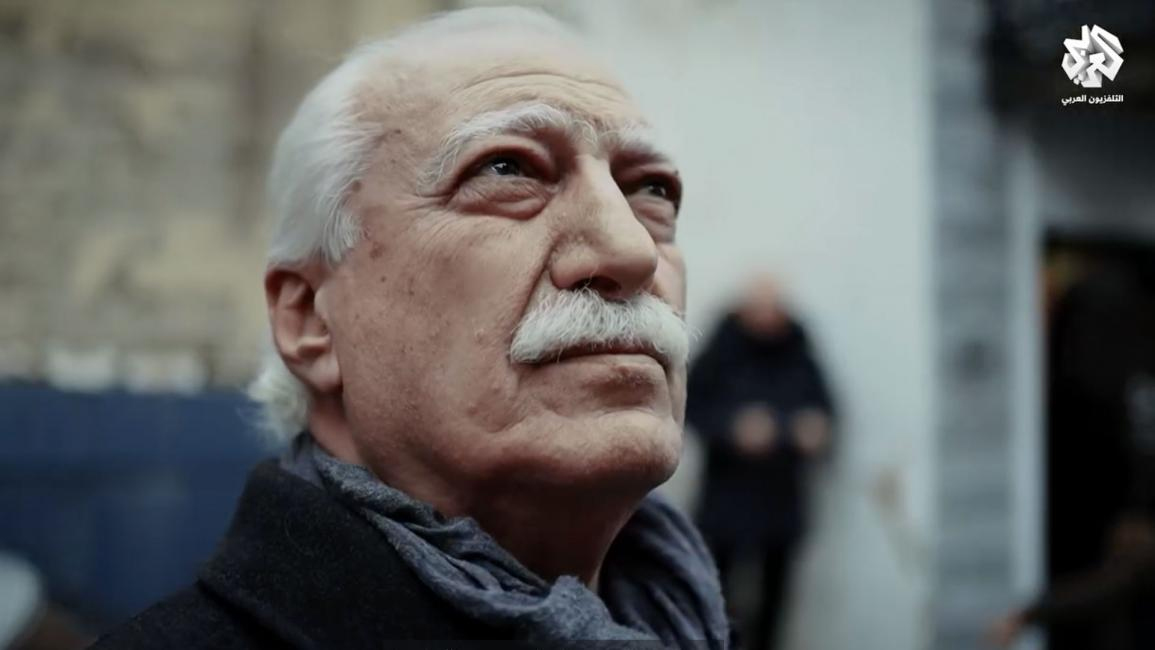

Samar Yazbek on Syria’s Oppressive History of Manufacturing Female Vulnerability

The questions of freedom and equality remain on the minds of many Syrians as the country navigates not only change, emerging from the Assad regime’s decades-long grasp, but also the recent tragedies of the coastal massacres. Liberating the country from tyranny extends beyond resolving its systemic judicial and political issues, but must also be re-examined from a fundamental human rights perspective.