Essays and Features

‘Unimaginative’ Digital Age: What Can Arab Cultural Journalism Learn?

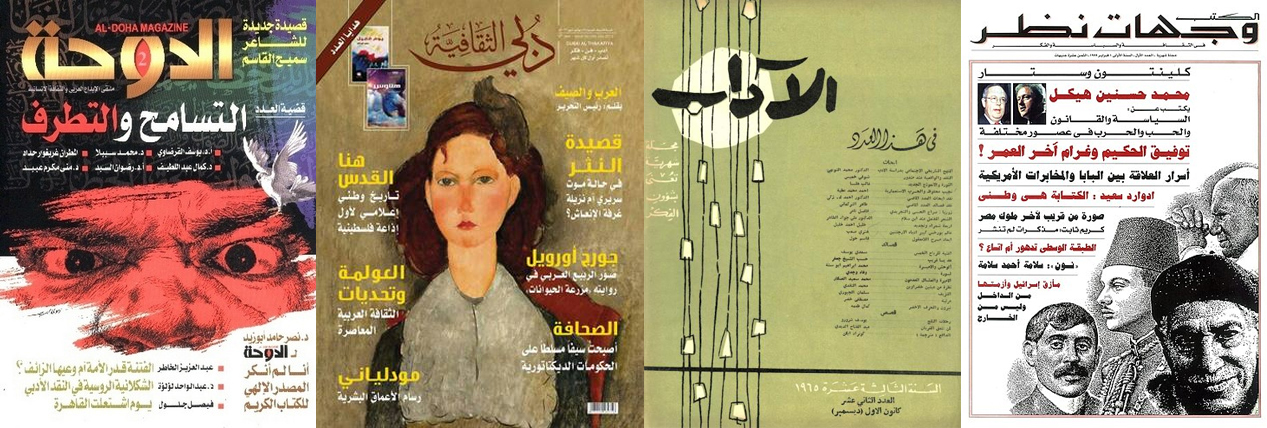

The Information Revolution and the spread of the internet and social media have had severe repercussions for cultural services as we know them. The loss of numerous publications remains one symptom of the many changes sweeping across the Arab world, which recently witnessed the closure of another publication, the Qatari cultural magazine Doha.

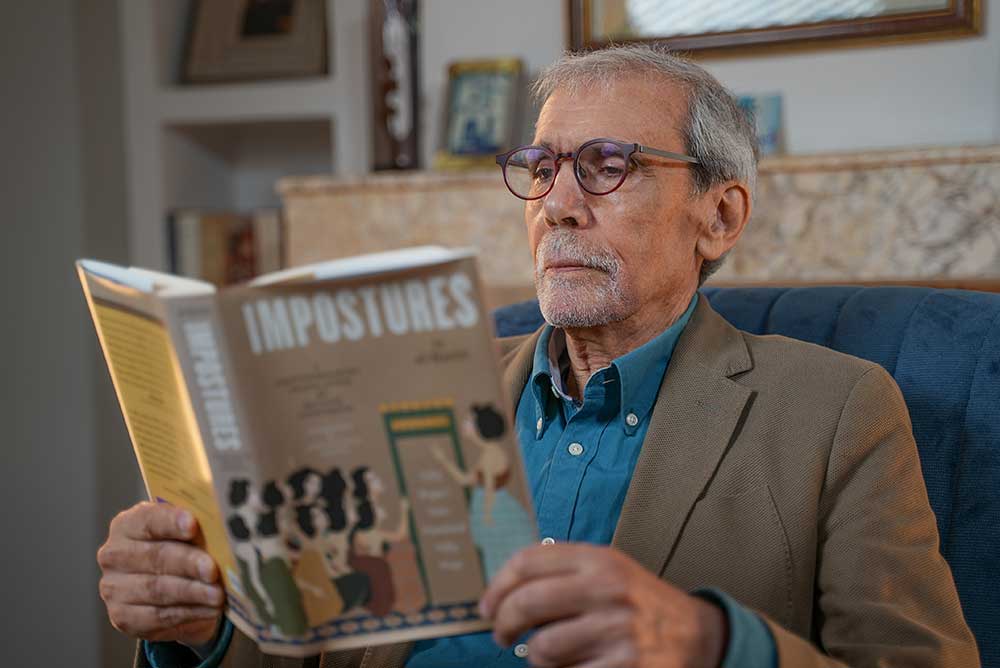

Grand Prix de la Francophonie Marks Pinnacle of Abdelfattah Kilito’s Profound Impact on Ancient Arabic Literary Traditions

‘Little Prince,’ Poet and Artist Hassan Abdallah Evoked the Beauty of Nature Through Boundless Streams of Vibrant, Passionate, Paradoxical Language

After his passing in 2022, poets, intellectuals, and journalists offered their eulogies of the Lebanese poet Hassan Abdallah (1943-2022), who captivated readers with his words. Among those honoring him were Shawqi Bzay, Abbas Beydoun, Jawdat Fakhreddine, Talal Salman, and others. Without exception, Abdallah’s colleagues and friends remember him as a humble man, one who preferred to remain in the shadows and shun the limelight, festivals, and fiery speeches.

Drawing the Curtains on Wajdi Mouawad’s ‘Controversial’ Play: Lebanese Intellectuals’ Defense of Director Warns of State Chokehold on Freedom of Expression

“Theatrical” perhaps best describes the current state of Lebanon’s performing arts scene, which seems to be embroiled in its own drama in recent days. Early this year, we bade farewell to the director and actor duo Antoine and Latifa Multaqa, pioneers of Lebanese theater’s 1960s avant-garde era and, for a moment, relished in nostalgia for Beirut’s culturally vibrant bygone days. Unfortunately, such rose-tinted memories have little room under the stifling atmosphere overtaking much of Lebanon’s arts and culture.