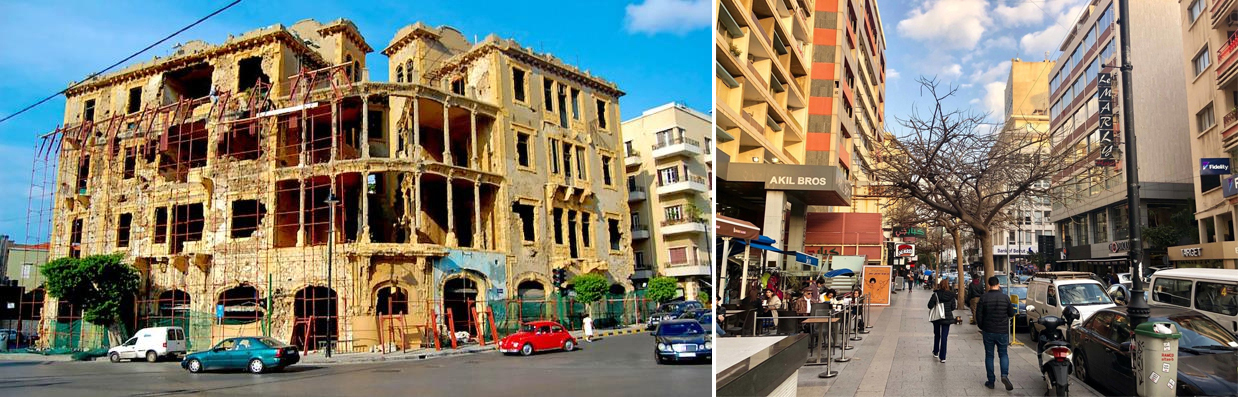

On the left, Bayt Beirut, also known as the Yellow House, prior to its restoration; on the right, a web-based photograph of Hamra Street, Beirut.

When Lebanon is in crisis, and even when it is not, laypeople and some experts rush to use popularized and romanticized explanations suggesting that the country is experiencing something unprecedented. They reminisce and claim Lebanon had a much better time in the “good old days.” If the crises are financial and economic, they proclaim that Lebanon enjoyed economic growth, stability, high employment, and increased incomes in the pre-crisis days. If the crisis is the collapse of law and order and the rise of rampant crime, they respond that stability and domestic peace were the distinctive marks of the good old days.

Experts and political elites employ this comforting, inactive strategy to avoid implementing fundamental social and economic reforms that address the current crisis. Since the underlying basis behind this approach is conservative and apologetic to the old order, they default to the “romantic” past and avoid facing the present, reminiscing about old policies that provided stability and domestic peace — a golden age.

Some find these ideas appealing because they romanticize the past. But this wishful thinking is not without its criticism. By idealizing otherwise difficult times, we absolve the past of its responsibility for some of the current troubles. It is, at best, an apology.

This metaphor of our everyday perceptions is addressed in Ghassan Ismail Abdel Khaleq’s new book, “The Myth of the Beautiful Time, Towards a New Enlightenment Culture,” in which he discusses how we idealize the past as beautiful times that we cannot repeat. In its glorification, the myth is creatively arranged and sanctified by the imagination, making it one of the most significant obstacles to the renewal and change we desire.

Author Abdel Khaleq maintains that the term “Beautiful Time” represents the most prominent cultural, artistic, political, economic, and social metaphor in Arab life, according to the London-based Al Arab newspaper. He added, “I would not be exaggerating if I also said this metaphor represents the most dangerous type of mental drug because of the intentional or unintentional deception it entails for the individual and collective self alike, and because it conceals the veils of excessive romanticism, which are nothing more than a thick layer of overwhelming pathological nostalgia.”

Unquestionably, this nostalgia for the Lebanese past is pathological and deceptive, mainly when some use the past to paint a picture of half-truths. Yes, Lebanon had some good old times at some point, but they were not what some zealous Lebanese portray today. They compare the incomparable conditions, overlooking that these “supposedly good times” gave birth to deadly civil war, one of the consequences of which is the crisis facing the country today.

Abdel Khaleq furthers that the metaphor used, as cited by psychologists, is fueled by a contemporary Arab imagination of a “comfort zone” to hide behind. This is done to justify their extreme fear of undertaking, individually and collectively, policies or initiatives of modernization and innovation to address current problems.

The implication of this metaphor makes decision-makers reluctant to engage in change. It exaggerates dangers around the trend towards political democracy, intellectual freedom, and cultural diversity at the collective level. The metaphor also invokes a sense of guilt whenever we question the recent or distant past, pushing us to praise our “lost paradise,” which, were we bold enough, we would realize was not flawless.

Abdel Khaleq acknowledges that the above does not mean we must break away from the past. Instead, he implores us to “weed it and cleanse it of harmful weeds that obscure its magnificent fruit trees.” Rather than presenting his study as a series of sermons, he hopes to shock readers from the complacency of the “beautiful time” and the captivity of the comfort zone.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 28, No. 85, 2024 and Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 88, 2024.

Copyright © 2024 AL JADID MAGAZINE