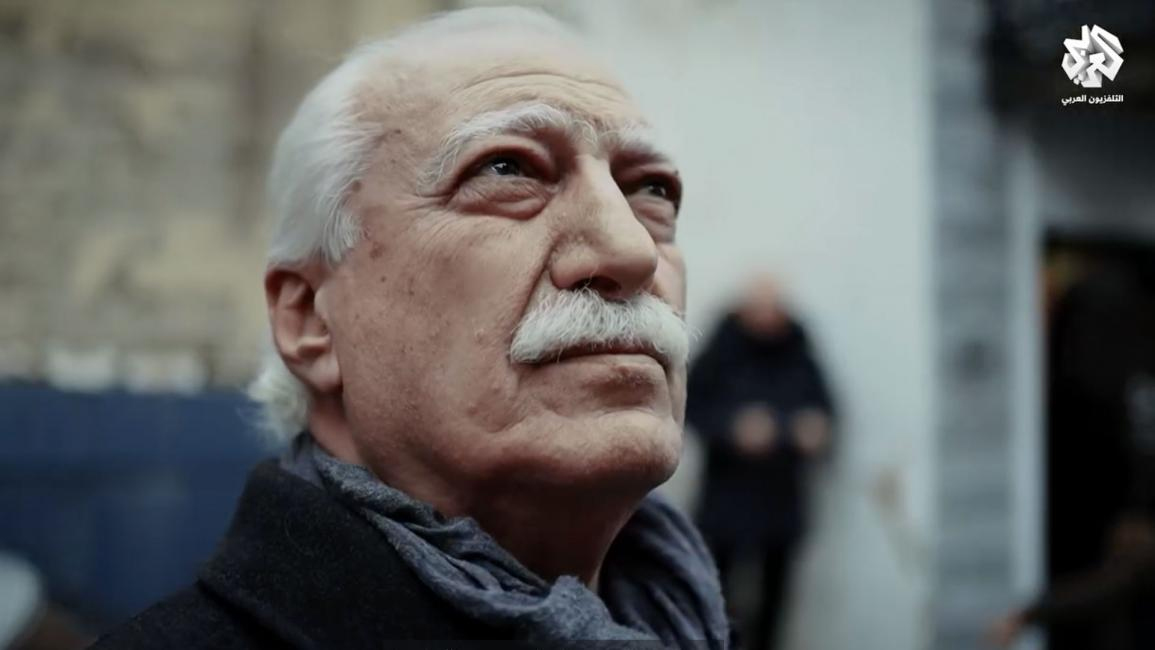

The legendary and controversial Iraqi poet Saadi Youssef died at 87 in his Harefield home outside of London on June 12 from lung cancer. The poet, whose multitude of works encompassed poetry, prose, literary criticism, translation, and memoir, leaves decades’ worth of work penned in exile and translated into several languages, among them English, French, German, and Italian.

A Judge Runs Amok

While much of the country — and even the world — focused on the last U.S. election and remained engrossed even after its results and consequences, the picture of this historic event in the Arab world was unlike anything that was happening here. Regrettably, the distorted analysis and coverage by Arab media influenced to some extent the attitudes and electoral choices of many Arab immigrants in the U.S.