Cultured Women and the Fragmented Self in Arab Fiction

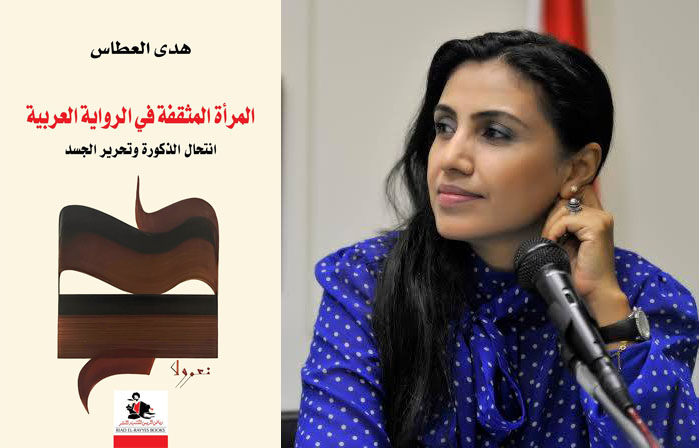

Author Huda al-Attas and the cover of her book, “The Cultured Woman in the Arab Novel: Appropriating Masculinity and Liberating the Body” (Riad Al Rayyes Books and Publishing, 2026).

Arab women have paved their own paths in the Arab social and cultural sphere throughout history — especially in the early to mid-20th century — by any means possible, whether as writers, leaders, teachers, or founders of clubs, magazines, and movements. Like in reality, women’s determination to secure their positions in fiction is layered with complex barriers. A valuable addition to the Arab critical library, Yemeni writer and researcher Huda al-Attas’ new book, “The Cultured Woman in the Arab Novel: Appropriating Masculinity and Liberating the Body” (Riad Al Rayyes Books and Publishing, 2026), examines the presence and portrayal of women in Arab fiction, going beyond superficial analyses of women as social and emotional beings to question the ways culture, knowledge, and femininity intersect with her existence. Ali Jazo reviews the book in an article for Al Modon, “The Cultured Woman’ by Huda al-Attas: The Imitation of Masculinity and the Suspended Being.”*

Attas makes a distinction between the cultured woman and the educated woman. The cultured woman is considered so because of her awareness, her questioning of her surroundings and reality, and her capacity for independent thought, qualities reflected in her attitude toward society, authority, and selfhood. Meanwhile, the educated woman may not carry the same critical awareness or intellectual stance towards reality. Attas’ research is led by an overarching inquiry: how has the character of the cultured woman established herself in narratives that have historically adhered to male-centered perspectives? In the words of Ali Jazo, Attas’ analysis suggests that “many educated female characters have only found a way to achieve narrative and cultural recognition through what Attas calls ‘masculine impersonation,’ that is, adopting a system of values, behaviors, and language traditionally attributed to men — the husband, lover, and father, all in one unchanging entity.”

In Arab society, a woman’s sense of personhood and autonomy cannot be extricated from the patriarchal constraints surrounding her existence. Religions, customs, and traditions are used to legitimize male authority over women, who are treated as subjects, possessions, objects, and tied to a man’s honor. “The female body is not viewed as a natural given, but rather as a symbolic burden that threatens the legitimacy of the cultured woman,” writes Jazo, who clarifies that because they view their bodies as a burden, these characters resort to “neutralizing, denying, or re-assigning symbolism to it, striving for self-liberation through knowledge.”

Such actions yield mixed results. Attas questions the success of this form of liberation, noting that, in both fiction and reality, the cultured woman attains an advanced cultural position at the expense of alienating herself from her body and her original identity. As Jazo states, “Culture can become a psychological burden for the female novelist and narrator” — her awareness makes her more conscious of the contradictions of reality and more sensitive to the gap between herself and her surroundings. This leads to increased feelings of isolation and loneliness. However, Attas notes that this feeling of alienation can be presented as either a defeat or represent a form of silent resistance.

Attas’ book surveys the evolution of the portrayal of women in the Arab novel. Jazo notes that, in the early stages of modern Arab narrative, women were cast in traditional roles as mother, wife, lover, or victim. “With the development of social and cultural awareness, the novel began to grant women a wider space for self-expression, and the model of the cultured woman emerged as a product of transformations in Arab society and its engagement with modernity,” he writes. The presentation of the cultured woman in the narrative plays a vital role. Attas discusses how techniques such as autobiographical narration, first-person perspective, interior monologue, and stream of consciousness can reveal the character’s psychological and intellectual depth. “These techniques contribute to shifting the woman’s voice from the margins to the center,” explains Jazo, adding that female writers tend to portray more complex and authentic female characters that stem from real-life experiences and struggles, though this is not absolute, as successful examples exist from both male and female writers.

Attas asserts that the presence of the cultured woman in the novel is both decorative and problematic, as she doubly acts as a source of conflict within the narrative. In the words of Jazo, "This character is frequently placed in confrontation with prevailing value systems, experiencing an internal struggle between self-awareness and the desire for freedom on one hand, and the social constraints that encircle her on the other. The study demonstrates that this conflict constitutes a central element in the construction of the fictional character and gives the text a cultured and psychological dimension." According to Attas, as cited by Jazo, Arab novels often portray the cultured woman as a subject of suspicion because she disrupts the image of the obedient woman and seeks to assert her own voice.

Jazo concludes that the cultured woman is neither an ideal nor complete model, but rather a “troubled, questioning figure who experiences her struggles within the text as she does in reality.” He writes, “Attas’ work stands out for its specific focus on the cultured woman and for treating her relationship to the body not as a site of definitive liberation, but as a difficult negotiation with patriarchal authority.”

*Ali Jazo’s essay, ‘"The Cultured Woman’ by Huda al-Attas: The Imitation of Masculinity and the Suspended Being,” was published in Arabic in Al Modon.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 155, 2026.

Copyright © 2026 AL JADID MAGAZINE