Between the Silence of Taboo and the Cry of Despair

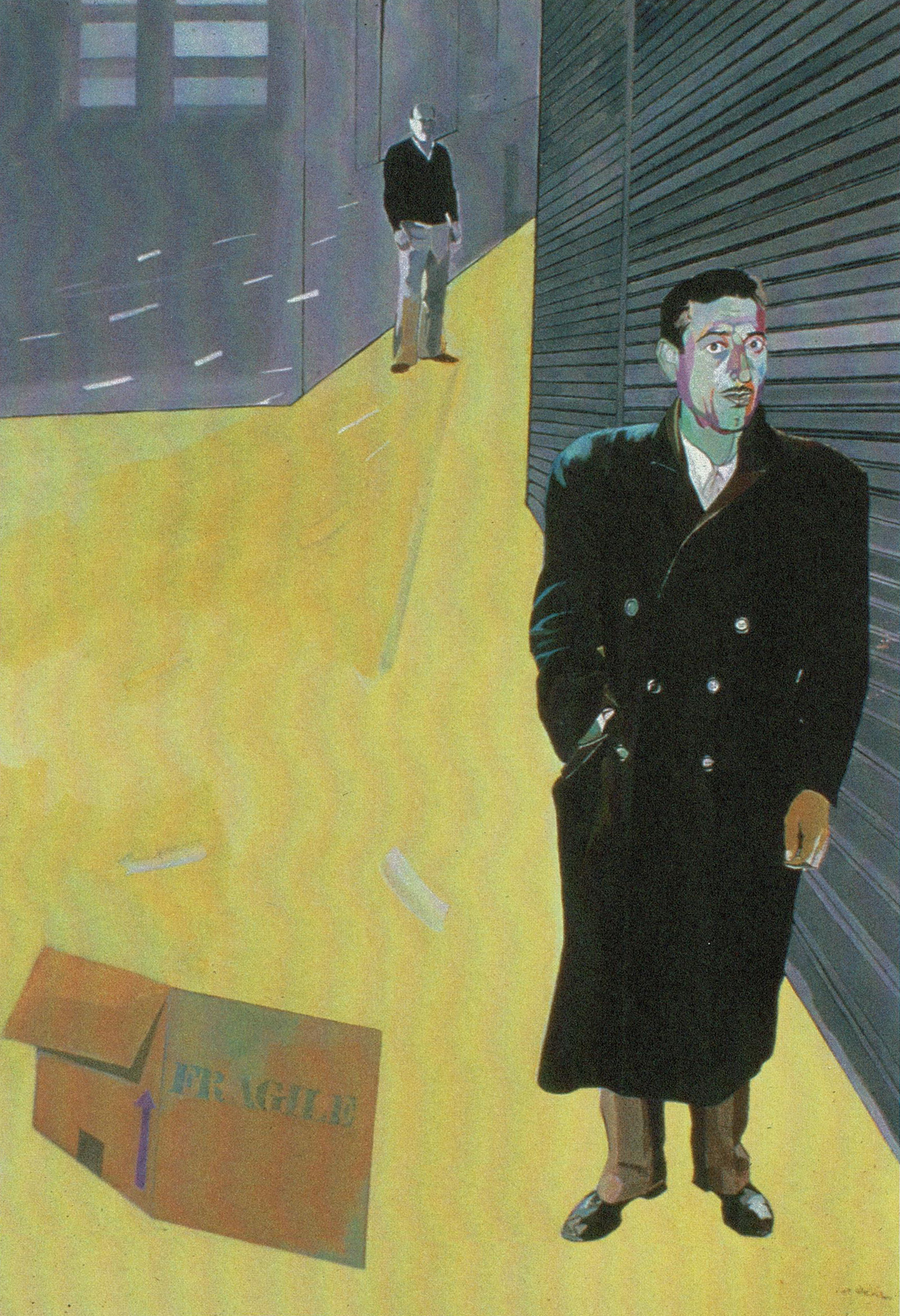

"Fragile" (1983) by Seta Manoukian.

The 10th of September every year marks World Suicide Prevention Day. The International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) and World Health Organization (WHO) estimate more than 720,000 suicides occur each year worldwide. Large-scale studies conducted on a global level find that the rates of suicidality (encompassing suicidal ideation, plans, attempts, and death by suicide) are low in the Arab world compared to other countries. 2019 statistics from the World Health Organization reported that countries within the Arab world held figures between 2.0 to 4.8 suicides per 100k (with Syria reporting 2.0 and Iraq 3.6 per 100k).

The loss of any life cannot be overlooked, no matter the number. Suicide and mental illness remain taboo topics in the Arab world, and as a result, suicidality within these regions is underreported and underestimated. The subject of suicide in the Arab world often falls under two categories. On a societal level, specifically in Islamic societies, it is stigmatized and considered forbidden and shameful, not only to the reputation of the victim, but their families as well. Meanwhile, on a literary or symbolic level, such deaths are often poeticized and glorified. Wadih Saadeh writes in his poem “The Beauty of the One Passing On,” for example: “The most beautiful of us are the ones departing. The most beautiful of us are the suicides. Who wanted nothing and whom nothing took in completely. Those who took one step in the river, enough to discover the waters.”

Of the scarce amount of suicides that have been publically acknowledged, many have been poets and writers. In the 20th century, Arabs witnessed the tragic losses of Egyptian poet, writer, and women’s rights advocate Doria Shafik (1908-1975), who jumped to her death from her balcony, Lebanese modernist poet Khalil Hawi (1919-1982), who died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, and many others, raising concerns over what Ridwan al-Sayyed refers to in a 1997 As-Safir article as the “suicide of the creative mind.”*

French sociologist Émile Durkheim in his book “Suicide” (1897) links the motives for suicide to egoism, altruism, fatalism, and anomie (a state of confusion, disorientation, and a breakdown of social norms and standards within a society or group). Though suicide as a subject of study is underrepresented in the Arab world, three books do not flinch away from the topic: “Suicide in Arabic Literature” by Khalil al-Sheikh, “Suicide of Intellectuals and Current Issues in Arab Culture” by Muhammad Jaber al-Ansari, and “Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes” by Joumana Haddad.

Ridwan al-Sayyed reviews Khalil al-Sheikh’s “Suicide in Arabic Literature” in As-Safir. The book investigates the phenomenon of suicide among modern Arab writers while tracing its presence in medieval Arab culture. Sheikh identifies three types of suicide used by Arabs during the medieval ages and as recorded in folktales or biographies. The first is ‘suicide by choice,’ or the belief that death is one’s only choice due to inability to secure sustenance. The second, death by physical means — through blood loss, self-inflicted stabbing, falling from great heights — were options given to captives or prisoners allowing them to choose the manner of their end. The third form of suicide involved drinking alcohol excessively and self-destructively, a method used by medieval tribal elders who, having lost influence within the family or been deprived of leadership, chose death over humiliation. Of these methods, Sheikh suggests that the first two forms of suicide were coercive rather than “true” suicides, considered suicide only in a technical sense and better observed as social phenomena — the tribal customs of that age. Similarly, he does not consider ritual death as suicide in either the Freudian or the ancient Arab sense. Meanwhile, he finds that the third form aligns most closely with the modern perception of suicide; that is, suicide as an individual’s chosen response to an existential experience.

Sheikh distinguishes the perception of suicide from a medieval Arab perspective and modern anthropological and literary studies. In the words of Sayyed, “Khalil al-Sheikh thus treats suicide in classical Arabic literature and popular tales as both a human experience and a revelation of selfhood among sensitive characters — often poets and writers. In the modern era, however, the phenomenon is approached as part of the literary biography — suicide as an extension or consummation of the creative experience.”

In analyzing suicide in the modern era, Sheikh suggests that Arab writers and intellectuals’ suicides “are complex acts of protest through which the self seeks redemption” and that these writers may consider their own deaths as “another chapter in [an] ongoing self-narration.”

Muhammad Jaber al-Ansari’s “Suicide of Intellectuals and Current Issues in Arab Culture” pinpoints two factors contributing to the rise of suicide among intellectuals, the first being a ‘lack of harmony’ — “a disconnect between the individual intellectual and others, the world, and their self” — and the second being ‘emotional failure’ — the inability to form stable, meaningful emotional relationships, as cited by Raed Aleid in “The Gasp of Despair: Reflections on the Biographies of Those Who Committed Suicide,” published on the online platform MANA.**

Lebanese poet Joumana Haddad’s “Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes” is a compilation of poems, translated by Haddad, written by 150 poets who committed suicide in the 20th century across 48 different countries. The book’s concept drew from her memory of her grandmother’s suicide when she was five years old. Haddad writes, “I kept seeing suicide as poetry until I saw it. I mean until I saw it with my own eyes. When we see mutilated and torn bodies, there is no longer the poetry of the act, but rather the ugliness of the result itself,” as quoted by Aleid.

As Ibrahim Musharat writes in his essay “On World Suicide Prevention Day: Why Do Arab Writers and Poets Take Their Own Lives?”, published in Al-Quds Al-Arabi, reasons behind the suicides of Arab creatives and intellectuals often come down to “literary failure, romantic failure, poverty, illness, political and social crises, an a pessimistic disposition.”*** Individuals may view life as an “illusion and deceptive mirage,” with death, on the converse, as “the only fixed reality.”

Countless Arab poets and writers committed suicide throughout the 20th century, whose stories are recorded in Musharat’s article: the Egyptian writer Ismail Adham committed suicide in 1940, having felt alienated due to his inclination towards atheism. He lived in isolation, depression, and frustration. Egyptian poet Ahmed al-Asy, a medical student who was unable to complete his studies due to illness and poverty, committed suicide in 1930. The aforementioned Egyptian writer Doria Shafik ended her life in 1975 after 18 years of isolation, confinement, and having her works and presence erased from the public. Other Arab writers lost to suicide include the poet Fakhri Abu al-Saud (1909-1940), Enayat al-Zayyat (1936-1963), Waguih Ghali (1927-1969), Salah Jahin (1930-1986), and Arwa Saleh (1951-1997), among many others.

Often, writers chose suicide in response to the hopelessness they felt about their societies and lives. War-related trauma and political violence pose a risk factor for Lebanese adults, according to a study conducted by Elie G. Karam et al. in “Temperament and suicide: A national study.”**** Jordanian poet Taysir Subou’s suicide in 1973 was linked to despair regarding the Arab reality and setbacks, along with health problems. The death by self-inflicted gunshot wound of Khalil Hawi, one of the most famously known suicides, was in response to the Israeli invasion of Beirut, writes Musharat. A pan-Arab nationalist poet who often wrote about Arab unity, Hawi lost hope after the 1967 defeat and 1982 invasion of Beirut. Musharat adds that the writer had lived in isolation and was also suffering from a brain tumor and seizure-like symptoms for which he sought treatment, but treatments ultimately failed.

The Arab world witnessed another surge in suicidality in 2011, sparked by the public suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit seller who burned himself to death on December 17, 2010 after being harassed by officials, insulted, and having his cart confiscated, igniting the chain of protests that would culminate in the Tunisian Revolution and Arab Spring of 2011. In the weeks following his death, suicides (often by self-immolation or hanging) increased in Tunisia and across Egypt, as cited by Tom de Castella in “The Death of a Tunisian Poet and the Hidden Story of Arab Mental Health,” published in the BBC News.*****

Among those who have died to suicide in recent years, the Tunisian blogger and poet Nidal Gharibi’s death garnered attention on social media and news. In March 2018, Gharibi committed suicide after posting a farewell message on Facebook. He reportedly was struggling to find a job, and his friends told the BBC that “his depression was exacerbated by the political and economic situation in Tunisia.”

Psychologists affirm suicide is the culmination of a long depressive trajectory, a “withdrawal from society, severing of ties between the individual and community, family estrangement, alienation from oneself, and a collapse of trust in everything,” states Musharat.

A BBC News Arabic survey of the Middle East and North Africa indicates that four in 10 Tunisians are depressed. Of the over 25,000 people interviewed by the research network Arab Barometer for the BBC News Arabic survey, a third of the respondents in the region said they were depressed. The same survey finds that “only Iraqis are more likely to report feeling depressed across the 10 countries, plus the Palestinian territories, that were surveyed.” Because stigmas associated with mental health problems may prevent many from reporting, figures could be even higher. According to Najila Arfa of the civil society group Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights, suicide deaths and attempts reached a peak of 857 in 2016, as cited by Tom de Castella.

Ibrahim Musharat urges that “those who die by suicide do not hate life — clinging to life is an instinct shared by all — but rather lose the ability to bear pain under the weight of nihilism and despair.” As turmoil across the Arab world — war, internal conflicts, political and economic instability — continue unabated, however, the loss of creative minds remains a concern. In Musharat’s words, “At major civilizational turning points, when a nation is in desperate need of its intellectuals to defend its interests and to combat tyranny, corruption, subservience, class injustice, ignorance, poverty, and illiteracy, there is no path but to align with the people’s hopes. Anything else is suicide…It is a message and a cry, like a distress call from a sinking ship before all aboard go down.”

*Ridwan al-Sayyed’s review of “Suicide in Arabic Literature” was published in Arabic in As-Safir, Issue 7800.

**Raed Aleid’s essay, “The Gasp of Despair: Reflections on the Biographies of Those Who Committed Suicide,” was published in the online platform MANA.

***Ibrahim Musharat’s essay, “On World Suicide Prevention Day: Why Do Arab Writers and Poets Take Their Own Lives?”, was published in Arabic in Al-Quds Al-Arabi.

****Karam, Elie G et al. “Temperament and suicide: A national study.” Journal of affective disorders vol. 184 (2015).

*****Tom de Castella’s essay, “The death of a Tunisian poet and the hidden story of Arab mental health by Tom de Castella,” was published in BBC News.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 145, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE