Hoda Barakat and the Mythology of Loss in Lebanon

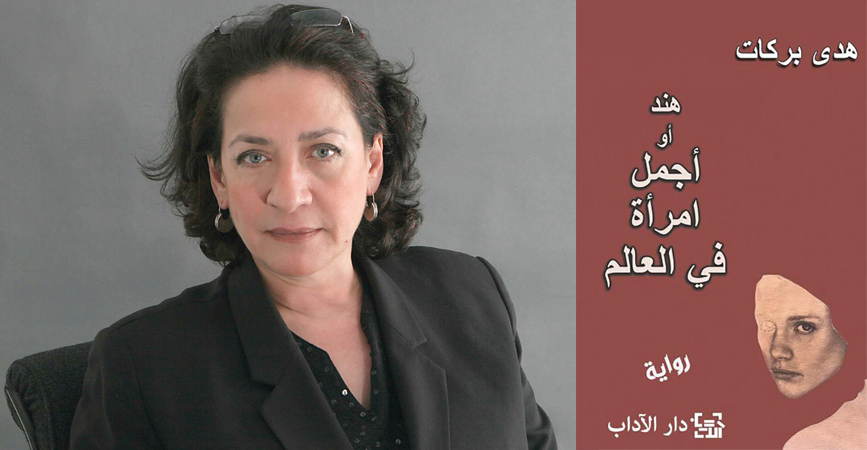

On the left, a web-based photograph of author Hoda Barakat. On the right, the cover of “Hind, or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World” (Dar al-Adab, 2024) by Hoda Barakat.

Between living in the memory of beauty, deliberately blind to its flaws, and living in beauty’s shadow, perpetually weighed down by the past, Hanadi’s story is a portrait of more than a woman disregarded by both family and society, but an encapsulation of all the problems plaguing Lebanon, in fiction and reality. Life, death, and all its dualities intersect in Hoda Barakat’s prize-winning “Hind, or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World” (Dar al-Adab, 2024), which was chosen among a shortlist of three novels for the 2025 Sheikh Zayed Book Award. Described as bleak yet paradoxically serene by critics, this is a novel of “slow disintegration, dissolution and annihilation, and acceptance of them,” writes Tariq Abi Samra in Al Majalla.* “This is precisely what Hanadi, the heroine and narrator of this novel, seeks: to be erased little by little until she vanishes into nothingness.”

“Hind, or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World” takes place after the Beirut Port explosion of August 2020 has left an already-spiraling Lebanon teetering on the cliff’s edge. Told in the first person, the narrative begins with Hanadi’s return to Lebanon from her exile in France after the death of her mother. The events of the novel occur as Hanadi’s memories, whether from her childhood or her more recent past. “But Hanadi's actual life is a constant regression; she piles up memories; indeed, she is nothing but these memories," states Abbas Beydoun in The New Arab.** In the words of Hanadi herself: "I did not return to this country out of love or longing. Rather, it was because God's vast earth rejected me. I found myself on the sand, at the edge of the waves, like a dead whale."

At a young age, Hanadi was praised for her beauty and doted on by her mother. Beauty standards are a core presence in Hanadi’s plight. While the titular character Hind never appears in the flesh or as a memory, she seems to haunt the narrative as a specter that never leaves Hanadi. Hind, who died a few years before Hanadi was born, was so adored by their mother for her beauty that when Hanadi was born, she was only viewed as a replacement for the beautiful first daughter. However, Hanadi is soon afflicted with acromegaly, a hormonal disorder causing the enlargement of limbs and facial deformities. Hanadi, once considered exceedingly beautiful, is stripped of humanity and dignity, reduced to a monstrous animal in the narrative. In the words of Beydoun, “Hanadi, thus, will no longer be human except from afar; she is neither a woman nor a man, nor a human, nor an animal. She is all of that.” In this way, Beydoun finds many similarities in Hanadi’s character to Gregor Samsa of Franz Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.”

Her mother’s love transforms into a repulsed shame and she hides Hanadi away from the world, isolating her from the world by locking her in the kitchen attic for months on end. As Abi Samra states, “This psychotic mother’s behavior leads the reader to question the veracity of the story of the first child who died; perhaps Hind was merely the product of her mother’s hallucinations, unable to bear her daughter’s deformity and ugliness, so she split her into two people.”

Confined to the attic, Hanadi feels as if the only way to liberate both herself and her mother from her shame is by running away. She escapes to her aunt’s house, where she lives for a while before her aunt convinces her to stay in Paris with another aunt. The plan is a ruse to get rid of Hanadi, however, and she arrives in France with neither family nor belongings to her name. In the words of Lena Abd Rahman in Independent Arabia, “The novel exposes the psychological blemishes hidden behind physical disabilities, raising implicit questions about the idea of mercy and human nobility. What is the true face of mercy? Does it truly lie in motherhood? Do blood ties warrant nobility towards the weak who need someone to care for them?”***

Alone and homeless in Paris, Hanadi encounters numerous characters and even falls in love with a man named Rashid, who she feels truly loves her, but leaves him due to his drunken violent outbursts. Returning to Lebanon after hearing the news of her mother’s death, Hanadi is preparing to die — her joints hurt, she is losing her teeth, and her eyesight is failing, writes Abi Samra. Her only companion is a cat named Zakia who is also deformed, having only three legs and one eye.

“Hind, or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World” is a narrative depicting “a life ruled by the dead,” writes Abd Rahman. In it, “the past always haunts the present and…one cannot separate oneself from one’s roots or the people who have left their mark on one’s life. The novel explores the relationship between beauty and mortality, where beauty appears not as a purely positive quality, but as a double-edged sword, carrying within it the tragedies of loneliness, isolation, emotional generosity, and psychological stinginess.” She adds: “Barakat combines linguistic simplicity and spontaneity of storytelling with the complexity of subconscious psychological ideas, intertwining them with a lively and vibrant philosophical vision that questions the nature of human communication with those close to us.”

The duality of the relationship between homeland and exile is also symbolically reflected in the duality of ugliness and beauty, according to Mubarak. The novel’s discussion of beauty and its glorification is an extension of Lebanon’s state of collapse. Hanadi’s plight may resonate with the complicated feelings surrounding exile, yearning for the homeland, and disappointment upon return to the motherland. In the same way, her mother serves as a metaphor; just as she sees Hind as the most beautiful woman in the world, so too do others view Lebanon with rose-tinted lenses, blind to its flaws, as “the most beautiful homeland in the world,” in the words of Micheline Mubarak in the New Arab.**** As Hanadi explains in the novel, “My mother’s disappointment, her bleeding wound, was because, with my illness, she was no longer able to reclaim Hind.” Hind, like the shining, golden Lebanon of the past that many yearn for, is something beyond reach.

“It is as if it [Lebanon] has regressed to a pre-civilization era and continues its regression toward extinction: no electricity, bank accounts evaporated overnight, extreme poverty spreading like an epidemic, garbage piled up in the streets, groups of teenagers and children begging by day and getting drunk at night, sometimes assaulting passersby,” writes Tariq Abi Samra. In Lebanon, Hanadi resigns herself to death, hoping to reach a state of stagnation. Abi Samra adds, “Her only consolation is that she is finally in her place, she who has always lived on the margins of everything, who has never had a place anywhere. She is now in her place, in this once-beautiful country, which was distorted and has become ugly beyond imagination. A country that is no longer a country, a country that is gradually disappearing on its way to nothingness, just like the heroine of the novel.”

The novel explores beauty standards in the ways they affect the lives of those living on the margins of society. Hoda Barakat has frequently shone a light on the weak, powerless, alienated, and those “who hesitate and have no ideological or other reference that reassures them” in her characters, as she explains in an interview with Publishers Weekly. According to the same interview, while Barakat has not had personal experience with acromegaly, she hoped not only to explore bodily physical deformities, but also the “ugliness and deformity of modern cities.” She states, “I felt the ugliness and deformity of modern cities, or cities described as such, as a physical assault on my eyes and even on my whole body. The light, the temperature, the way you breathe, everything is altered and corrupted. And Beirut in particular was already destroyed by the long years of civil war. Too beautiful before, we went into denial. In our quest to make ourselves feel less guilty, we invented a city out of nostalgia, or we continued to destroy it because it no longer resembled the one we knew.”

In a symposium held at the American University of Beirut, the author explains, quoted by Mubarak: “We are in a dilemma regarding the beauty of Lebanon. Our consciousness is formed by our love for this country and its description in a folkloric way. At the same time, it is a beautiful country, and we are confused about our relationship with this place. Additionally, in our country, we do not have a unified history textbook. What shapes our consciousness most are myths and legends.” Mythology is frequently referenced throughout the novel in Hanadi’s memory, from stories of saints, tales about the world of art, and recollections of “the good old days.” She deconstructs and criticizes these stories, “revealing their triviality,” writes Mubarak.

Hanadi’s slow death paints a metaphorically gloomy, yet honest landscape of Lebanon that is difficult for some to acknowledge. As Tariq Abi Samra aptly sums up, “It's as if the country itself is speaking to you, telling you the story of its dying moment, informing you that the time has come to say goodbye and that you must accept it. It's as if the country is mourning itself, but without any emotional excess, but rather with simplicity and dignity, which makes the elegy all the more harsh and painful.”

*Tariq Abi Samra’s essay, “Hind or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World’ by Hoda Barakat: Staring into Death and Annihilation, was published in Arabic in Al Majalla.

**Abbas Beydoun’s essay, "Hind, or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World’ by Hoda Barakat: Metamorphosis and Memory, was published in Arabic in The New Arab.

***Lena Abd Rahman’s essay, “Hoda Barakat Narrates the Broken Relationship Between a Mother and Her Deformed Daughter,” was published in Arabic in Independent Arabia.

****Micheline Mubarak’s essay, "Hind or the Most Beautiful Woman in the World’: The Duality of Life and Death, was published in Arabic in The New Arab.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 140, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE