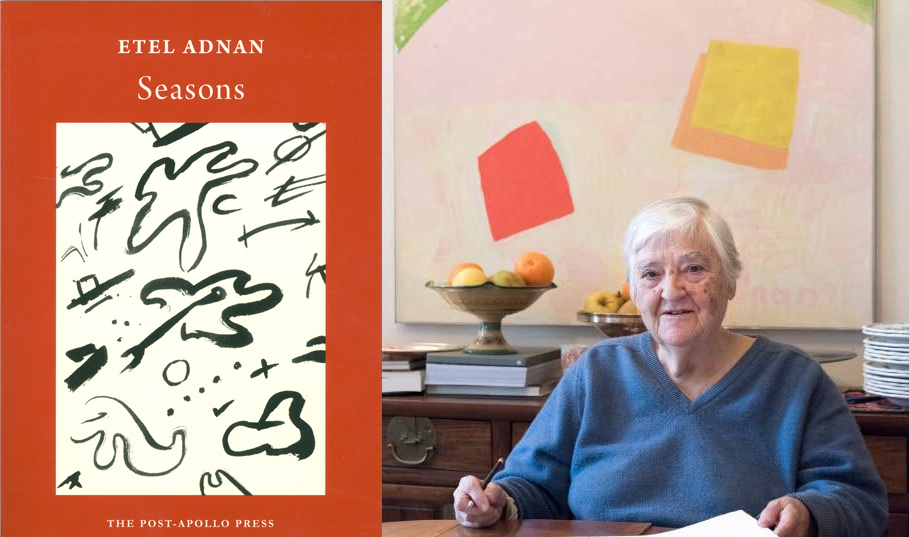

Web-based photograph of Etel Adnan.

Seasons

By Etel Adnan

The Post-Apollo Press, 2009

Listen to Etel Adnan’s voice in “Seasons,” her new book of poetry and meditations: “I want to walk in mountainous countries. Some nations are sitting and crying in front of screens larger than their borders. Their brains are starting to fall apart. I listen.” And as she listens, she teaches us to do the same, though it is quite challenging at first. For we quickly realize we are in the presence of a deeply intuitive, almost frenetically responsive mind. What are these “screens larger than their [countries’] borders?” Movie screens? Perhaps, if we are willing to accept the completely free license of the artist at work here. Imagine a movie screen larger than her native country of Lebanon, positioned in the sky above those timeless cedars, and revealing in anguishing replay the war of 1982. Shatila? Sabra? Again, perhaps. We do want a sense of logic, a sense of continuity, in what we read – and this is not to be the case with Etel Adnan’s “Seasons.” No. We are to enter an exquisitely imagined and private world, where “the oak tree is growing with anxiety,” and “no object can compete with a sound’s intimacy.”

Adnan’s is also a very kinetic world, bordering on the chaotic. “Time passes from right to left. Planets intrude on the sky. A rain of daffodils appeases the drought.” The earth is at once both the passive victim of an intrusion and a vigorously personified participant in the struggle for vivid life. Adnan’s daffodils have the human quality of empathy, of seeking to pacify a land stricken by drought.

Elsewhere, her voice is intensely probing, questioning the very nature of existence. “Being is invisible to all of the senses, why are these senses then excluded from the promise of thinking? Or are they? Is adhering to one’s own skin life’s sole purpose?” Being and “invisibility” both contend with and complement one another. “Non-Being is the invincible force that pushes Being up the hill. The same with sorrow.” There is a feeling of intense fear welling up from such lines. If Non-Being – death – is “invincible,” what is to save us from defeat if not simply a fear of the thing itself? Fear pushes us up the hill. Likewise, if we succumb to “sorrow,” will the shadow of Non-Being engulf us? “A woman goes to the cliff, and waits, standing, and non-visibility envelops her totally.”

In the valley below this cliff, in the sky above, war has left a lingering wound on the landscape, on the innocent victims, and on the soul of the poet. “Clouds are war’s first casualties. It’s a time when the description of paradise leads the mind to insurrection, chaos. The sky looms big in shallow pools on broken streets. A four-year-old Iraqi boy has been amputated of his two arms after an American air raid blew up his quarter. When he woke up, he asked, ‘When will I get them back?’” We’re forced to witness, and we remember.

But memory is the cruelest faculty of the soul in such times. Empty wine bottles line a window sill. “Can one break memory the way one breaks stone with stone? Is memory’s function to first break down, by its own means, then pick up the pieces and reassemble them, but clumsily, never in the way they used to be.” The question is its own answer. To ask is to already know. But if there is to be any release, it is through language, through poetry. “For insomniacs, mind – while all other things are excluded – plays games with itself. Then language, in those nights, reveals itself as being our essential self.”

And from those nights of revelation, Adnan seems to retrieve a sense of peace, acquiescence. “To run water in gutters and feed blue jays on berries is Nature’s perfect balancing act.” Such balance astounds us at times, until we detect a well-worn strain of bitter irony. This is not the peaceful life I would have preferred, she says, in essence. No, it is the life I’ve been asked and forced to accept. “Shiny red peppers! Green peppers! Women walk between tomatoes and leeks, in a season of war; that’s not unusual. It’s rather like swimming in the summer.”

And, it is this tenuous balancing act that sustains Etel Adnan’s vision and voice through the “seasons” of her years. “A childhood of thorns and roses.” Winter, spring, summer and fall. “For the poor, winter is natural habitat, with pockets empty, depleted, belly empty, in an abandoned garden between the high-rises.”

Etel Adnan’s meditations, and her poetry, are there in this “abandoned garden,” speaking to us, and for us, the lament we all must feel, with yet the hope we cannot deny, perched on “the cliff, and waiting.” We all wait with her.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 60, 2009.

Copyright © 2009 AL JADID MAGAZINE