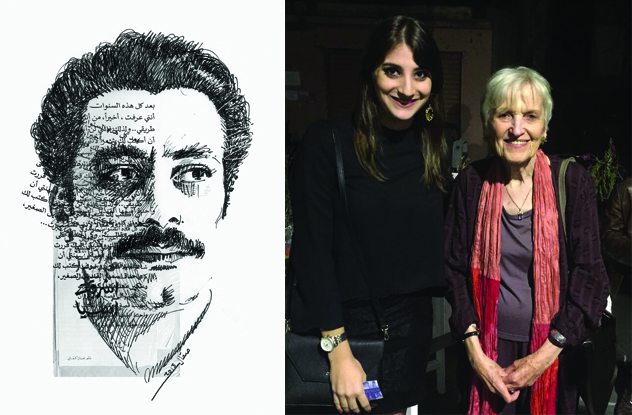

On the left, Ghassan Kanafani by Mamoun Sakkal for Al Jadid. On the right, Odette Yidi David, the author, with Anni Høver, Kanafani’s wife.

Now in Her 80s, Danish Wife of Assassinated Author/Activist Ghassan Kanafani Keeps The Flame of His Legacy Burning Bright

Ghassan Kanafani’s works continue to pulse with love and life for the Palestinian cause half a century after his death. In 2019, a film by Italian director Mario Rizzi gave a unique perspective on one of the late Palestinian author’s works, named after and centered on Kanafani’s fairytale “The Little Lantern.” His film was recently shown at the 2022 Palestinian Film Festival in Paris. Narration by his wife, the Danish activist and teacher Anni Hover, delves into her memories of Kanafani and his niece, Lamis, who died alongside him when he was assassinated in Lebanon in July 1972. Hover was in Beirut in support of the Palestinian cause when she met and fell in love with Kanafani in the 1960s, permanently moving to Lebanon. After his death, she chose to remain in Lebanon and devoted herself not only to preserving Kanafani’s legacy but also to preserving her connection with Palestine. She has opened numerous kindergartens in Palestinian camps. Children take a focal point in the film, and the narrative is framed by Rizzi’s adaptation of “The Little Lantern” theatrically performed by the children of one of these very kindergartens.

- Al Jadid

Ghassan Kanafani was a revolutionary figure both in his literary production and political involvement in the Palestinian national struggle. His literary sharpness and revolutionary ideals garnered him recognition throughout the Arab world as a prolific writer who made a seminal contribution to Palestinian and Arab literature. Nonetheless, this also precipitated his assassination in Beirut in the summer of 1972. Kanafani’s oeuvre reflects his political consciousness evolving through his literature, where he proposes alternative and revolutionary ways of engaging the masses in the struggle for Palestinian self-determination.Despite its literary and technical simplicity, the work “Umm Saad” (1969) is one of Kanafani’s major pieces because it shows a highly developed political consciousness and maturity. As Muhammad Siddiq argues in “Man is a Cause: Political Consciousness and the Fiction of Ghassan Kanafani,” Kanafani successfully weds literary technique to political objectives, and his fictional characters reflect the Palestinian condition. The expression of his mature political ideology reaches its epitome in proposing a revolutionizing shift in the traditional role of women in the context of the struggle through the literary field/context of Umm Saad. The simplistic style of the novel – expressed in the use of colloquial Arabic – his avoidance of artistic shortcomings that are contrastingly present in the novella “Returning to Haifa”; and through the elimination of the previous modernist endeavors of “All that’s left for you,” according to Siddiq, is congruent with the evolution of Kanafani’s political thought, his preeminent role in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and with his belief that the masses learn but can also teach.

Gendered Construction of the Nationalist Movement in Palestine

Understanding the representation of women in Palestinian literature requires unpacking the role of women in nationalist movements and the importance of literature in narrating, politicizing, and imagining the nation. Feminist scholar Cynthia Enloe argues in her “Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics” that women have had an uneasy relationship with nationalism since they have often been portrayed as symbols rather than as active protagonists in the struggle for liberation, despite having suffered the same abuses – or more – from the colonizers. Furthermore, she continues that with anticolonial struggles, women are usually seen as the nation’s most valuable possession; the vehicles for transmitting the nation’s values to coming generations; as bearers of the new generations or “nationalist wombs”; as the community’s most vulnerable members; and as the easiest targets for assimilation and co-opting. Thus, nationalism is indeed inclusive of women but primarily in terms of reproducing the nation “biologically, culturally, and symbolically,” as quoted by Nira Yuval-Davis in Amal Amireh’s “Between Complicity and Subversion: Body Politics in Palestinian National Narrative.”

Nationalism has further been gendered through the “maternal imagery” of women that prevails in nationalist literature around the world.This form of representation effectively positions women as “mothers of the nation,” according to Beth Baron’s “Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics.” Literature and nationalism have an intricate relationship, and literature is indeed a privileged medium for the nationalist discourse and for imagining the nation. As Benedict Anderson argues in “Rhetorics of Belonging: Nation, Narration and Israel/Palestine,” the novel is the national art form par excellence. Other scholars also highlight this primordial and dialectic relationship between nation and narration, like Timothy Brennan, who suggests that “The political tasks of modern nationalism directed the course of literature …and just as fundamentally, literature participated in the formation of nations through the creation of ‘national print media’—the newspaper and the novel,” as cited by Amireh.

Modern Palestinian literature is indeed characterized by a close interconnection with decisive events such as the 1948 catastrophe and the 1967 setback, and it has effectively played a major political role: Kanafani was actually the first in coining the term “resistance” when speaking of Palestinian literature, according to Barbara Harlow and Karen E. Riley in “Palestine’s Children: Returning to Haifa and Other Stories,” and has been key in “shaping how the post-1948 Palestinian experience has been understood,” as maintained by Amy Zalman in “Gender and the Palestinian Narrative of Return in Two Novels by Ghassan Kanafani.”

The Literature of Resistance and the Image of Umm Saad

Palestinian Resistance literature is by and large highly gendered. Portraying Palestine as a woman/mother, and the constructions of femininity and masculinity of the national discourse are essential elements of modern Palestinian literary works, especially those by Kanafani.. Palestine is, in both the literature and the resistance movement, represented as a female entity and as a woman whose honor must be defended. It is also described as a nurturing mother expecting her Palestinian sons to defend her, uphold her honor and protect her from the enemy’s aggressions. Kanafani effectively deploys this national traditional imagery of Palestine as a woman throughout Umm Saad as he inextricably associates, compares, and represents Palestine with the figure of Umm Saad herself, and vice versa.

Throughout the collection of short stories by the name of “Umm Saad,” physical features such as the skin, tears, arms, hands, height, and the smell of this refugee peasant mother are often associated with elements of nature such as dust, crop fields, wood, trees, soil, and water: Umm Saad is herself Mother-Earth. The story entitled “Difference between two tents” exposes the image of women as “nationalist wombs” when Umm Saad tells the narrator she wished she had 10 more children to give to the resistance.. This imagery arises again in the story “Guns in the Camp” when Abu Saad tells a man at the square while watching his younger son Said perform with the fedayeen that his wife “gives birth and Palestine takes [her offspring].”

Following the same line, in “At the heart of the shield,” women are portrayed as nurturers of the nation and caring mothers, and the Earth itself is feminized and portrayed as a mother that gives birth. In this story, Saad and his comrades are besieged by the Israeli army once they have crossed into Palestine and they risk being captured. A peasant woman is seen by Saad approaching their hiding place and he desperately calls her “my mother.” The woman turns her attention towards the call and “sees the spinous forest give birth to a young man,” and saves the commando unit by bringing them food. In “Guns in the Camp,” masculinities and femininities are put in trial when Abu Saad regains his masculinity previously lost due to the loss of Palestine, and which had made him miserable. After having his son Saad participate in the armed struggle, he reclaims his masculinity and becomes more optimistic and kinder towards Umm Saad.

Umm Saad, the Revolutionary Mother

The deployment of women as fighters in this collection can be understoodwithin the framework of the mature political consciousness of the author in the time of writing. Kanafani’s Marxist background is openly shown in his eminent portrayal of the peasant: some scholars even argue that his portrayal of the Palestinian peasant after and before the 1948 catastrophe is his most important achievement, since until that breakthrough, Arabic literary tradition seldom portrayed them sympathetically, according to Hilary Kilpatrick’s Men in the Sun & Other Palestinian Stories.” The image of the peasant is highly politicized by the Palestinian national discourse and this is thoroughly evident in Kanafani’s writings. The peasant is a national signifier in the Palestinian narrative as Ted Swedenburg’s renowned “The Palistinian Peasant as National Signifier” proposes: the peasant is a historical agent, a national icon, and the symbolic site where the nation gathers together, mobilizes, and sees itself in a settler colonialist context in which ownership and control of the land is the central theme of dispute. Yet, despite this symbolic importance, the figure of the peasant lacks political consciousness in the official historiography and is subjected to guidance from others while engaged in the nationalist cause: far from being a protagonist of the revolution, peasants are the keepers of tradition, and the fedayeen – not the peasantry – are the movers of history.

Kanafani reproduces this peasant image in Umm Saad but eventually breaks with tradition by allowing her to develop a political consciousness of her own derived from the hardships and experiences in the refugee camp of Burj Al Barajneh where she has been living since being forced out from her village of Al Ghabisiyya in 1948. Various passages give the reader hints of Kanafani’s conscious deployment of Umm Saad as a politically-aware agent of change rather than only as the traditional peasant and nurturing mother that, nevertheless, he shows in parallel as well. In the story “Those who left and those who progressed,” Umm Saad gathers women, children, and youngsters to remove the debris after an air raid, and to move the cars off the road to avoid them being hit by the fighter jets and their missiles. This readiness to take the struggle in her own hands comes again throughout the text as Umm Saad mentions her desire to take weapons and go to the camps where her son and other fedayeen are.

But perhaps the most notorious moment of political awareness of the peasant Umm Saad is provided in the first story “Umm Saad and the war that ended.” Here, she recounts that her son has been imprisoned but that she is confident that he will one day leave, and she believes that their lives and the refugee camp have also been a prison for the past 20 years. In these lines, we can see reflected Kanafani’s own political conviction in which Palestine would be liberated through a social and political revolution in the Arab world: the jails of patriarchy, class oppression, and foreign occupation would eventually be defeated by a collective armed and Marxist revolution, as suggested in “Engendering Resistance in the Work of Ghassan Kanafani: All That’s Left to You, Of Men and Guns, and Umm Sa’d” by Nancy Coffin. The fact that Kanafani chooses to depict a woman as the peasant protagonist of the novel and further gives this peasant an independent political consciousness, allows us to see the deployment of women in both Kanafani’s literary creation and political thought.

Conclusion: Innovation and Confrontation

Palestinian literature of resistance contains a primordial political consciousness and is in constant dialogue with the political context. Kanafani successfully returns agency to the peasant and to women in Umm Saad: his political convictions allow him to see beyond traditional patriarchal structures of society, and he gives the responsibility of the social, economic, political, and cultural revolution to the masses, beyond gender. The renowned Egyptian author Radwa Ashur accused Kanafani of reasserting the image of women as a mother in Umm Saad and argues that her political contributions positioned her more as a revolutionary mother rather than as a revolutionary itself. She further criticizes the author’s backwardness towards women in contrast to his adherence to progressive revolutionary values, as cited by Coffin.

The merging of the mother and the revolutionary figure in Umm Saad that eventually leads to a “mother revolutionary” figure is a novel contribution to the Palestinian literature of resistance. It provided, in the time it was written, a fresh look that accorded with the particular political dominant discourse that Kanafani adopted. This “revolutionary mother” image does fall short in removing the maternal character and avoiding the feminization of the homeland, but still provides a powerful insight into Kanafani’s political thought and literary innovation in comparison to his previous works where neither women nor peasants had a leading role, in both the text and the struggle. This, at last, is the biggest contribution of Ghassan Kanafani with “Umm Saad.”

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 24, No. 78, 2020.

Copyright © 2022 AL JADID MAGAZINE