The exhibition “Visible Migration Patterns” shown at El Camino College Art Gallery, opened a fresh window into the complex inheritance of Arab culture present in the pioneering work of Doris Bittar. Curated by Susanna Meiers, this exhibition immersed viewers in an interplay of colors, patterns, Arabic writing, and visions of people through a range of media, including paint, photos, collage, shadow boxes, painted sound objects, and installation art.

Currently a resident of San Diego, Doris Bittar is an award-winning interdisciplinary artist whose work explores her cross-cultural heritage and reveals the complex relationships between Euro-American and Arab cultures. Bittar was born in Baghdad to Lebanese and Palestinian parents, an early childhood spent in the outskirts of Beirut, later immigrating with her parents to New York. These experiences made Doris acutely aware of the richness and complexity inherent in people’s cultural origins. As Susanna Meiers relates in her introduction to the exhibition catalog, while still in high school “Doris began a life-long dedication to an artistic practice that synthesizes passion for cultural history and human rights advocacy.”

“Visible Migration Patterns” not only encapsulates the artist’s interests in diverse artistic media but also her use of incessant patterns, which underscores her intense fascination with the interactive effect of one culture upon another. Doris Bittar’s fascination with patterns became immediately evident upon entering the first exhibition room, with its colorful display of monumental shaped canvases, layered paper cutouts, suspended-in-space paper gongs, and multimedia “Tarab Soundings.” Surprisingly for the viewer, the works on display engaged several senses immediately, inviting interaction in the monumental 5-foot diameter “Paper Gong” (2018), made out of overlapping security-envelope windows and glued into an irregular circle created by various patterns and shapes. “Paper Gong” was located at the entrance, and along with “Tarab Soundings” (2013), displayed on the main exhibition wall farthest from the entrance, the two works framed the exhibition experience, both of them performed by the artist during the opening.

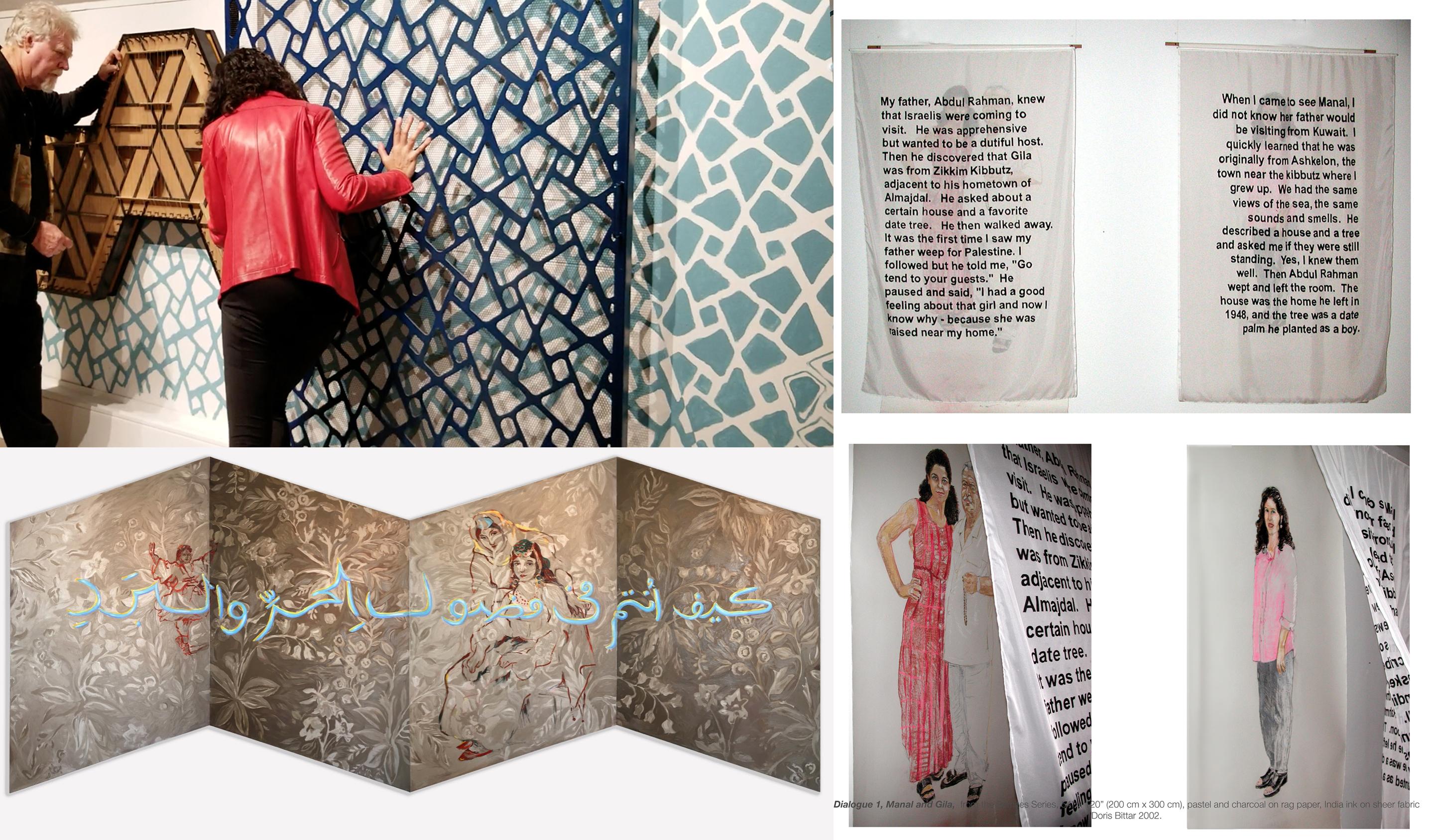

Building from her research into migrating patterns, the “Tarab Soundings” installation featured the dulcimoon, a unique stringed instrument producing a Celtic-style musical weave. Doris explains that she was attracted to this pattern because of its obscure cultural origin, attributed variously to Chinese and African sources, which “then mutated into Persian, Arabian, Japanese, Anatolian, and Byzantine forms,” as she puts it. In order to create this interactive installation that comprises a wall painting, a movable patterned steel frame, guitar strings, and hexagonal sound boxes, the artist collaborated with the microtonal musician Jonathan Glasier, who synthesized the sounds of several Mediterranean cultures into one instrument.

Both interactive installations are part of the “Performing Patterns” series that Doris initiated in 2010, the year she embarked on her philosophical quest to map how cultures emerge and shift. By employing movement, music, and patterns, she hopes “to enable the viewers to thread and share their identities with one another.”

Doris Bittar’s current work extends her earlier series “Migrating Patterns,” an ongoing incubator project that explores sources of patterns and fashions new ones. In the piece “Encoded Histories 3 Migration to the North” (2015), a map revealed through several layers of hand-cut paper, imprinted with colorful curvy triangles, traces the origin and spread of certain patterns. These curvy angles, the artist explains, “probably came from ancient sources in Egyptian and Greco-Roman designs.” The map featured in this piece suggests that these designs further developed in Byzantine Italy and Eastern Europe, and then traveled east to Damascus and across the Mediterranean to Andalusia in Spain with the Umayyad rulers.

Other works on display reflect a particularly dominant pattern that Doris Bittar arbitrarily named “Al Majed” (meaning “the Glorious One”) after first encountering it as a wood carving in the Al Majed Hotel in Damascus in 2005. Later, she traced it to Chinese wooden windows and ceramics in Agra, India, where it perhaps arrived as a migrating pattern along the Silk Road trades routes. In the drawings, constructed collages, and photo-based prints on display, Doris translates this pattern into three-dimensional lattices, exploring an ambiguous illusion of space within dark, night-themed drawings. Analyzing the artist’s fixation on patterns, the critic Robert Pincus rightly observes that “pattern itself becomes an emblem of cultural migration and connectedness” in Bittar’s art. Indeed, the wide-ranging works in the first exhibition gallery instantly provided viewers with a greater grasp of Arabic culture and invited them to contemplate its broad reach, while appreciating how patterns form connections between varied cultures and nations.

Fascination with Arabic writing long preceded Bittar’s fixation on migrating patterns. The gallery also featured her large-scale oil painting from the earliest series in this exhibition, “People of the Book” (1992-1997). The bright blue line written in Arabic script, “How Fare You in the Seasons of Heat and Cold,” floats in space across gold-tinted zigzag canvases, elegantly painted with floral motifs and images of oriental women. The shape of the painting, its luminous color, and its Arabic inscription give the viewer rich visual clues evoking nostalgia for the golden era of Arab culture. A close examination reveals that all floral imagery in this painting derive from French wallpaper designs, while images of the Arab mother and daughter in bridal attire originate from Delacroix’s watercolors completed during his 1832 visit to Algeria and Morocco, where he painted his personal translator’s wife and daughter.

The title of the painting – “How Fare You Are in the Seasons of Heat and Cold?” – comes from the poem “Joseph” by the Palestinian poet Samih al-Qasim, who spoke of the cultural climate and of the difficulty of Palestinian self-determination. Doris adeptly appropriates and weaves together various sources to convey the complex relationship not only between the various “peoples of the book” in the Middle East, but also between European and Arabic cultures. As she states, “I traverse the three Abrahamic faiths, often framed in zigzag and other minimalist structures to show their contemporary legacy and past complex harmony.” Indeed, Bittar’s intricately painted canvas reminds us that the histories of those peoples are tightly woven in daily interactions and in the building of Arab culture.

Doris Bittar’s complex engagement with Arabic writing has increased in her new series of work “And Wow” (2012-2018). Works on display such as “And Wow: Damascus Stamped Diagram Red” (2018) allowed the viewer to delve deeply into the meaning and design of the word “and,” which is graphically represented in Arabic language by the letter “Wow.” An indispensable word in both Arabic and English, Doris passionately explores its pictographic roots and visual qualities by suspending it in space like a bow, twisting, inverting, shadowing, and layering it, all while pushing the limits of its readability. In her varied visual experiments, ranging from photographic and pigmented prints to stamped diagrams and paper cut-outs, the artist playfully, yet adeptly, demystifies the Arabic script for the gallery goers. Discovering its capacity for spatial illusion, she relates it to architectural environments and the human figure. For Doris, Arabic letters can act like pillars, anchors, and figures “levitating, interacting, and articulating intimate to vast spaces.” This smaller-scale and more intimate series of works sets a new standard for an engaging and visually stimulating, yet playfully accessible, conceptual work.

“Visible Migration Patterns” also presented the viewer with an additional layer of complexity in understanding Arabs and Jews, through an installation of portraits and stories in one of the smallest and most intimate rooms of the gallery. The “Semites” (2002-2004) series, comprising large charcoal and pastel portraits in semi-photographic frontal poses coupled with short narratives handwritten on sheer fabric suspended in front of the drawings, invited the audience to explore personal stories of Holocaust survivors, Israelis, Syrian and third-generation Palestinian refugees, and immigrants. Doris collaborated with her husband James Rauch to form Jewish-Palestinian dialogue groups in San Diego in 2001-2006, to bring together like-minded and peace-loving people “to forge a community working to transform our future of co-existence.” Doris’s installation work created a special environment where the narratives of Israelis can coexist side-by-side with the narratives of Palestinians, without threatening or diminishing each other.

“Visible Migration Patterns” suggests that we take a new vantage point on the cultural climate in the Middle East. Through deft juxtapositions and inviting walk-through installations, this exhibition taught an important lesson of alternate relationships: if Jews, Christians, and Muslims coexisted peacefully in Lebanon and the Middle East before, so they might again.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 23, No. 76, 2019.

Copyright © 2019 AL JADID MAGAZINE