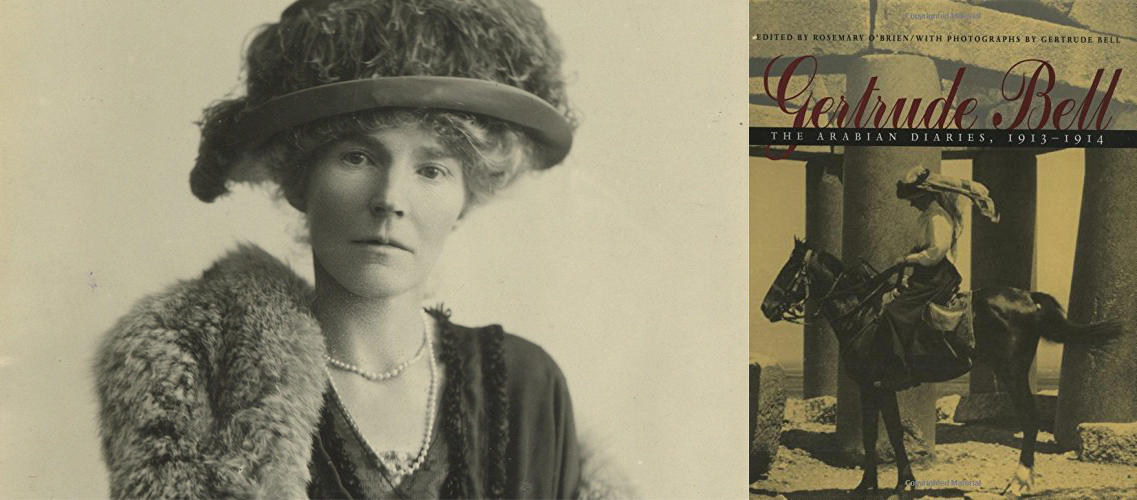

Gertrude Bell: The Arabian Diaries, 1913-1914

Edited by Rosemary O’Brien, with photographs by Gertrude Bell

New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926), the well-known English traveler, archaeologist, and political agent, is perhaps more famous in the annals of British imperialism for her role in molding the post-WWI politics of Mesopotamia in 1921, bringing Faysal to the throne of Iraq, and later, as Oriental secretary to the British High Commissioner in Baghdad, reporting to her government in London on the Iraqi domestic, political, and societal affairs she tried to influence. But these achievements built on her activities in the previous two or three decades which, in their own right, were as daring and adventurous, as politically astute, and socially uncommon among women of her time as the activities of her subsequent Iraqi period. Rosemary O’Brien, an editor and retired freelance journalist now living in Princeton, NJ, has put historians in her debt by editing Gertrude Bell’s previously unpublished Arabian diaries of 1913-1914, housed in the Robinson Library at the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne; O’Brien has thus given readers a glimpse of this remarkable woman’s past.

The diaries give an account of Gertrude Bell’s journey on camel back, starting in December of 1913 from Damascus, traveling southward through present-day Jordan and south-east to Ha’il in Arabia, then north-east to Najaf and Baghdad in Mesopotamia, and westward back to Damascus which she reached in May of 1914. It is an arduous journey even with today’s modern means of transportation. She had to hire dependable Arab men as guides and guards; carry water, provisions, and tents; equip herself with weapons, cameras, film, and various lenses, binoculars, and writing materials; and above all be ready for the unexpected. Bell had to deal with the Ottomans, who tenuously ruled the desert, and meet with hostile Arabian tribes. For example, Jabal Shammar was contested at the time by Ibn Saud and Ibn Rashid until the Saudis finally won with British support.

Gertrude Bell’s aim was to chart new approaches to the oasis of Ha’il and hopefully to interview its ruler and write a book about her journey on her return to England, adding to her former publications. One suspects she harbored more personal motives: perhaps to be away from her bourgeois homeland with its lingering Victorian ethics and to lead an independent woman’s life – an adventurous one at that.

Rosemary O’Brien supplies an interesting but brief biography of Gertrude Bell as an introduction to the edited diaries. She weaves information derived from those diaries as well as from “The Letters of Gertrude Bell,” published in 1927, and other sources. We learn that Gertrude Bell, whose mother died when Gertrude was three, grew up excessively dependent on her father, an industrialist who had inherited the ironworks of her grandfather, a Liberal member of Parliament (1875-1880) in Disraeli’s second ministry. British imperialism was in its most aggressive, interventionist period and Gertrude Bell learned about international affairs from early childhood, and her interest was stimulated further as a student at Queen’s College in London and later at Oxford University. O’Brien explains that while on a visit in 1892 to her stepmother’s diplomat relatives in Teheran, Bell accepted a marriage proposal from the legation’s secretary, Gerald Cadogan, but her parents disapproved and recalled her home. This visit and her earlier preparations for it compelled her to learn Farsi and Arabic, and resulted in her 1894 book “Persian Pictures” and in 1897’s “Poems from the Divan of Hafiz.”

She followed the visit to Tehran with several journeys to the Near East; her adventures there banished her boredom with social life at home and sublimated her frustrated sexuality which had been awakened in Tehran. Bell wrote about her adventures, and these publications aroused the interest of the British Foreign Office, hungry for information on growing German influence in the area. Her interest in archaeology provided cover for her at Germans sites, and indeed she did produce illustrated treatises on early Islamic architecture. She also first met and became friends with T.E. Lawrence at an archaeological dig in southern Turkey in 1911; that friendship later paved the way for her political rise in Iraq. Another important meeting took place at Konia in Asia Minor, where she stopped in 1906 to pick up her mail on her way back home from Syria. There she met the British military vice-consul, Major Charles Doughty-Wylie and fell madly in love with him. Though he was a married man, they exchanged romantic letters and met again in London and elsewhere, drawn together by their shared loneliness, but the situation was impossible.

Gertrude Bell kept her Arabian diaries of 1913-1914 in two notebooks for later reporting to the British ambassador in Constantinople. However, she sent a more refined and expanded version of them to her lover, Major Charles Doughty-Wylie, with some references in them to how much she missed him; these constitute the bulk of Rosemary O’Brien’s edited book. O’Brien includes the two notebooks of diaries in the same volume, but in smaller font. One can compare the two versions, and it is interesting to note Gertrude Bell’s elegant style in the Doughty-Wylie version, exhibiting a semblance of order, and then to read her hastily recorded brief impressions in the two notebooks. Both versions benefit from her observant eye that captures natural scenery, human personalities, daily events, and varying moods of expectation, fear, and anxiety. Her photographs of Arab men and women, of desert scenery and historical ruins, of her camels and caravan companions render her text more vivid.

The information in her diaries was useful to British troops in the Great War, especially details about the routes and water sources in the desert and the conditions and attitudes of Arab tribes and their leaders in the area. Military geographers, imperial administrators, and policy makers have also found Bell’s careful work useful. Despite the romantic notion of travel in “the mystical East” that Gertrude Bell’s book exhibits, readers should not forget that she was a product of British capitalist imperialism and aggressive industrialist colonialism. Her writings served the expansionist drive of her country, providing knowledge that helped them obtain power over weaker people.

This review appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 33, Summer 2000.

Copyright © 2000 AL JADID MAGAZINE