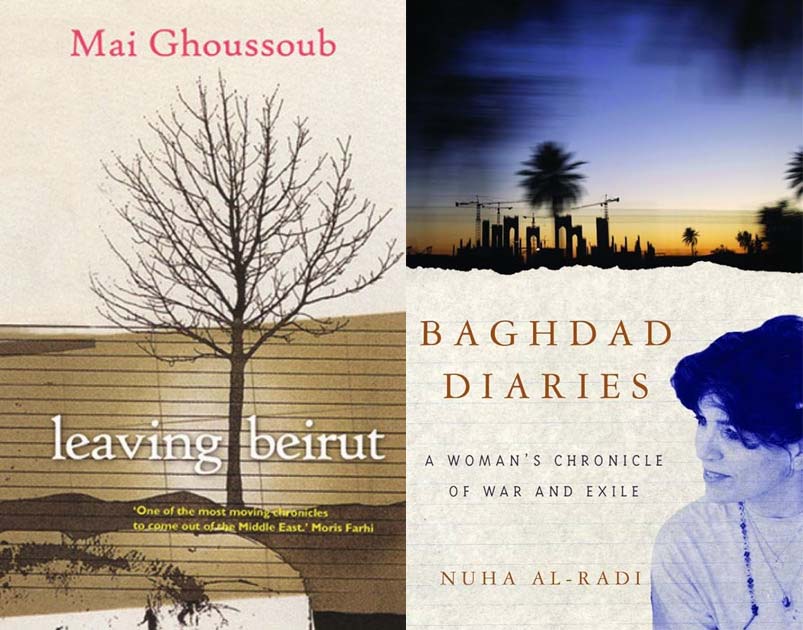

Leaving Beirut

By Mai Ghoussoub

Saqi Books, 1998

Baghdad Diaries

By Nuha al-Radi

Saqi Books, 1998

The question of what constitutes civilization and where the "road to barbarism" lies is the subject of two recent publications in English: Mai Ghoussoub's "Leaving Beirut" (Saqi, 1998) and Nuha al- Radi's "Baghdad Diaries" (Saqi, 1988). While the two approach the subject differently, they are both personal reflections on war and its aftermath, direct commentaries that convey the depth and intricacy of the issues confronting us as we deal with the collapse of civil society and its disintegration into what Ghoussoub calls the black and white of war.

Mai Ghoussoub's book is a complexly interwoven series of essays that stem from return to Beirut after the end of the Lebanese Civil War. The essays provide commentary and background to the process of reconstruction, to "the touch of amnesia that the Lebanese are cultivating so assiduously." In her attempt to deal with the new emerging society, she remembers the war through brief glimpses into specific incidents as well as her and others experience of exile away from the war itself. She does this by focusing on particular people who exemplify the dilemma she and others face as they, too, seek the security of amnesia. Among her characters are Umm Ali, the 16-year-old servant girl who becomes a fighter to escape the miserable conditions of her servitude; Said, the innocent grocer's son who turns into a sadist once he bears arms, showing the neighborhood children the cut-off ears of his victims; and the martyr Noha Samman who fascinates the nation as her video-taped recording appears on television just after she executes a suicide bombing.

| Ghoussoub skillfully takes the discussion even further than the values taught by the colonial system to various 20th century experiences of war and its aftermath. Following the issues of vengeance, justice, betrayal, and criminal liability, she addresses the betrayal of the Jews by ordinary French citizens to the Nazis, wondering how it is possible to "forgive and forget" such behavior. Speaking about war criminals, she quotes Primo Levi: "Monsters exist, but there are very few of them...Those who are dangerous are the ordinary men." |

As these people, along with others, come to life on the pages of "Leaving Beirut," Ghoussoub presents us with a number of recurring questions: how is the heroic defined? What is a war criminal? When is revenge justifiable? What is justice and, finally, what does betrayal mean? The questions are dealt with directly, through the characters we encounter. Not all of them are related to the war. For example, in "The Revenge of Leila's Grandmother" the author shows us a character, Fadwa, consumed by her drive to bring revenge upon her husband who almost abandoned her for another woman. Fadwa's obsessive vindictiveness eats her up, controlling her life entirely, driving her hopeless husband to an early death, and leading soon after to her own death as she loses a sense of purpose. Ghoussoub compares Fadwa to a woman she sees during the war who uses a hammer to attempt to kill a young prisoner from an opposite group in revenge for her brother's death the day before. In this case, Ghoussoub observes the general reaction to the women's behavior, as everyone, horrified, tries to pull her away from the young man. In what way, Ghoussoub wonders, is this need for vengeance different from the actual fighting itself, and why do the woman's actions appear more "barbaric" than that of the fighters who are killing each other?

The intimate portraits in the essays serve to ground a sophisticated and subtle discussion in the very concrete basis of Lebanon. Ghoussoub, however, reflects on a wider context by framing the essays as "letters" written to Mrs. Nomy, her childhood French teacher at the Lycee in Beirut. The reason for this framework emerges from a childhood episode that has continued to haunt her-an essay she wrote for Mrs. Nomy. Using the best French rhetoric drawn from literary sources, the child tried to impress the teacher by writing about an experience in which she takes revenge on some friends who treated her badly. Instead of the expected perfect grade, however, Mrs. Nomy fails the child, chiding her severely for what she calls her "despicable" behavior. Through her teacher, Ghoussoub learns that "revenge was the meanest of human sentiments, the most cowardly way one could behave."

While the two [Ghoussoub and al-Radi] approach the subject differently, they are both personal reflections on war and its aftermath, direct commentaries that convey the depth and intricacy of the issues confronting us as we deal with the collapse of civil society and its disintegration into what Ghoussoub calls the black and white of war. |

Mrs. Nomy's reaction in this instance exemplifies one of the ways in which Ghoussoub comes to learn conflicting values through her hybrid French-Arab background. The Arab/Mediterranean notion of "honor," for example, seen contemptuously through the lens of French education, apparently differs radically from the "honor" system the girls were encouraged to participate in. In this system, the girls were encouraged to look out for those who broke the rules and to report them to the teachers or administration; they were rewarded for such betrayals. Yet both cases involved a victim who was punished as a consequence, in the name of what was "acceptable," and a person who betrayed the victim, whether it was a brother/male relative or a classmate. Thus, while the concept of "honor" was represented differently in the two systems, in both cases they involved turning an ordinary person into a "criminal."

As Ghoussoub continues to consider and reflect on Mrs. Nomy's judgment, the issues involved turn more poignant when we learn that the teacher immigrated to Israel after 1967. Ghoussoub skillfully takes the discussion even further than the values taught by the colonial system to various 20th century experiences of war and its aftermath. Following the issues of vengeance, justice, betrayal, and criminal liability, she addresses the betrayal of the Jews by ordinary French citizens to the Nazis, wondering how it is possible to "forgive and forget" such behavior. Speaking about war criminals, she quotes Primo Levi: "Monsters exist, but there are very few of them...Those who are dangerous are the ordinary men." She writes on Said, the ordinary neighborhood grocery boy, who has returned after his atrocities during the war to work at the grocery in peace time, and wonders how she can bring herself to the point of amnesia where she can cross the road and enter his store to make purchases. Should he, in fact, be "forgiven?" Similarly, she talks about the many Jewish French citizens who were able to "forgive and forget," but also about those who, as victims themselves, sought retribution through victimizing Palestinians.

All in all, Ghoussoub provides us with numerous thought-provoking dilemmas that undermine any simplistic attempt to describe the experience of reconstruction. As in AEschylus' Orestia , she situates civil justice and the beginnings of civilization--the emergence from barbarism--as the movement away from "retribution and vengeance" to what Nelson Mandela calls "reparation but not retaliation." If we are to use Ghoussoub's terminology, within what form of retribution does the Siege of Iraq fall? As Ghoussoub puts it, does the punishment that the "International Community" imposed on the Iraqi people fall within the context of "civilized justice," a move away from barbarism? "Baghdad Diaries" provides us with an inside view of the population which is the victim of this system of justice.

While providing us with a crucial insight into the impact of the Gulf War and its aftermath on the Iraqis, in some ways "Baghdad Diaries" only provides a limited perspective. This is because al-Radi's experience is restricted to that of the most wealthy strata of Baghdad society--that of the land-owning aristocracy, members of the "old society." As a result, the focus of the diary is rather unusual, peppered with references to meetings with foreign dignitaries, cocktail parties, and luscious dinners. However, in some sense the trauma of the war is all the more striking, set as it is amidst another attempt at amnesia that focuses an inordinate amount of detail to describing the love life of the author's dog, Salvador Dali, and the strays that gather around him. Consequently we see that even the privileged, within their more sheltered environment, feel the jolt of the war severely as they are forced back into "Stone Age basics."

"Baghdad Diaries" painstakingly takes us through the early days of the bombardment, as even the most urbane sections of Baghdad succumb to a breakdown of basic amenities; the sewage system gives way to an orchard outhouse shared by many, water must be manually hauled in buckets to the water tanks on the roof, and heating depends on collecting wood from the orchard. As the bombardment ends and the sanctions begin, the physical breakdown of objects from windows to electric appliances (when/if there is electricity), begins to be felt as they become irreplaceable. As goods grow more scarce, the once-safe city of Baghdad falls victim to an increasing stream of burglaries that become more violent as time goes on. From a distance we hear about the more extreme situations the population must deal with. Rumors have it, for example, that "parents are beating up their children because they can then be hospitalized for up to three weeks--there they can be fed."

Among the details of everyday life, we learn of small matters with enormous impact. A shipment of food from the U.N. to Basra generates tremendous excitement, until people learn that those who receive U.N. rations "will have their Iraqi rations cut, or so say the rumors." Hospital supplies become so limited that those over the age of 50 are refused treatment in the interest of the younger generation. It is the younger generation, in fact, that shows the most dramatic increases in deaths; massive heart attacks in people in their early twenties, and a virus which kills in two days but which cannot be diagnosed because "there is no pathology lab to do post-mortems." As basic necessities become more and more scarce, the bureaucracy mounts higher and higher. This takes such an extreme form that the author comments: "People seem to be dying like flies. Ali says that if we ask for a permit to die, they'll say, 'Come back in a week and bring all your papers with you.'"

The most unforgettable parts of the diary are the references to the horrendous environmental toll the war has taken on the country. We see the author's rich orchard slowly whither away and die, as the flora is first invaded by unusual green insects, then the fruit begin to shrivel up. Isabel, a French environmentalist, claims that the destruction of the trees is a result of barium/barite bombs dropped on Iraq. People tell of an "orange wind" that blew from the south, and we later discover that the storm carried with it fallout from warheads that were blown up by the U.N. forces in a "hole in the ground," instead of the required concrete bunker with steel frame. Two simple metaphors serve to illustrate the damage that has occurred: a cockroach with a "curved back" that the author kills, and a sparrow with no tail. The mounting cynicism of the population as disaster strikes harder fills the pages with dark humor: "A strange abnormality -- many babies are being born dumb. It's probably better for them that way; they won't have a chance to talk against anything." As one Swiss epidemiologist remarks to the author, "This country is being used as a lab, with all of us as guinea pigs."

Al-Radi's "Baghdad Diaries" does not bring to her work the analytical considerations that Ghoussoub does, yet we are left asking similar questions: who should be tried for war crimes? Where does barbarism begin, and where can we look to for "civilization?" As Iraq is forced back into a "Stone Age" existence, with rampant disease, endless loss of lives, and a disrupted future for entire generations, where can we look for civil justice? "Baghdad Diaries" concludes optimistically, with a belief in the ability of art to communicate and to transcend the borders and boundaries set up by those in power to separate people. Ghoussoub's vision is more pessimistic and tormented, leaving us with a quote from Brecht to ponder: "The great political criminals... are not great political criminals, but people who permitted great political crimes."

This review appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 24, Summer 1998.

Copyright © 1998 AL JADID MAGAZINE