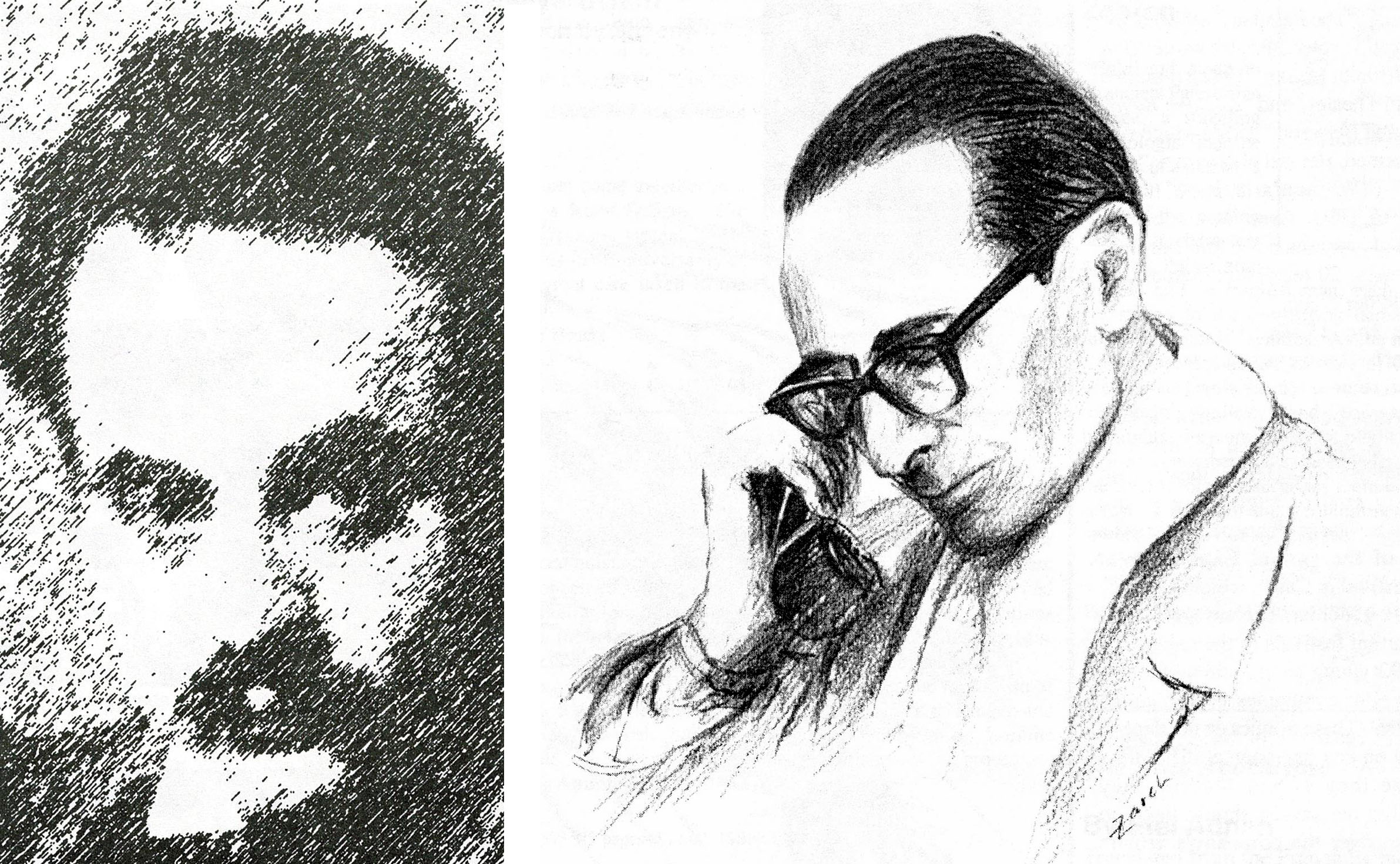

From left to right, artworks of Khalil Gibran by Emile Menhem and Georges Schehadeh by Zareh.

Last fall people in Beirut decided to honor the memory of Georges Schehadeh, a Lebanese poet and playwright who was born and raised in a Lebanese family in Alexandria, and who came to Lebanon when he was in his very early 20s.

The young Schehadeh became secretary to Gabriel Bounoure in 1930, when the latter was the Commissioner for Education for Lebanon and Syria. Bounoure remained in Lebanon until 1953, and while there founded the Ecole Superieure des Lettres, something like the French department of a university without the university. The Jesuit French University of Beirut attached this prestigious Ecole to itself in the early 1960s.

When the Ecole des Lettres was founded in 1944, Schehadeh was named its administrator rather than its director. As one of the first group of students (we numbered, I think, 10 or 12 for the first semester), I met Georges then. We became and remained friends until his death in Paris about a decade ago.

Thanks to their own beauty, and to Bounoure’s contacts in the literary world of the French capital, Schehadeh’s poems were published in some of the most sophisticated publishing houses of Paris. He was known in a small but important circle of famous French poets, among them Pierre Jean Jouve and Saint-John Perse.

In 1949 Schehadeh came to Paris as a member of the Lebanese delegation for UNESCO. In the meantime he had started his first play “Monsieur Bob’le” which was produced in a small theater, La Huchettet, and created quite a controversy. Then he wrote some seven plays, which were all produced by the famous company of Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud. Only one of his plays was produced in Lebanon, “L’Emigre’ de Brisbane,” as a part of the Baalbeck Festival. Also, the American University of Beirut produced, once, one of his plays, “Le Voyage,” in English translation.

Though known and celebrated in Paris, he was ignored in Lebanon. People knew his name and that he was a poet writing in French, but only a handful of people were reading his work. In the 1960s, when I was living in California, I used to go regularly to Lebanon in the summers and on the few occasions that I searched for one of his books at the “best” bookstore for books in French, La Librairie Antoine, I could not find more than one or two of his works! By then, Schehadeh was back in Lebanon, and his French wife, Brigitte, had opened an art gallery. Georges was often at the gallery, chatting with friends.

With the war in Lebanon, Georges and his family went into exile in Paris. He was extremely affected by the war; he was heartbroken. He had a profound attachment to Lebanon and to see it being destroyed practically destroyed his soul too. He died in Paris and is buried there.

Last winter, through January 2000, a Lebanese museum presented the first comprehensive public exhibit of Khalil Gibran’s paintings, watercolors, and drawings. That was a major artistic event and a good move by Lebanon to take stock of its cultural heritage. Simultaneously, the event honoring Schehadeh was taking place. It happened that I was in Beirut for a couple of months and I became interested in both events. One day I suddenly realized that these two literary figures were very different, which was evident, but it was suddenly clear to me their destinies had many points in common.

AN IMAGINARY WORLD

In all the volumes of poetry that Georges ever wrote, there is only one reference to a precise location: in one of his earliest poems he mentions Alexandria!

The settings of his plays are vague or imaginary: “Monsieur Bob’le” is in Paola Scala, a harbor of the poet’s imagination. Another “city” is Benvento. The only real city mentioned is Brisbane, his last work for the theater, “L’Emigré de Brisbane,” where that city is a metaphor for a far-away land, the way, in the 19th century, the mountain people of Lebanon used to say “in America” to mean any far-away place of no return.

It is remarkable that Gibran locates his “Prophet” in the city of Orfalese, an invented place (vaguely reminiscent of Urfa, in Turkey). Both “Bob’le” and “The Prophet” seem to be set in a no-man’s land. It is also remarkable that both these crucial works of Schehadeh and Gibran place their heroes, their main characters, in a harbor. Both heroes are at the point of departure, but neither really leaves: Bob’le dies without taking the boat which is waiting for him, and the Prophet leaves, as we surmise, to die, because he says that when he returns he will be the product of another woman’s womb than his mother’s.

Both writers give us the impression that their lives were lived under the overwhelming shadow of Exile. They are archetypal exiles.

Schehadeh was born and raised, as already mentioned, in Alexandria and came to Lebanon as a young man. His poems are dominated by the themes of childhood, the magic of churches, and the presence of gardens. His childhood is pervaded by a sense of innocent happiness; the churches, never denominated, are the Christian Orthodox churches of his faith, with the magic poetry of icons (icons being a recurrent theme), and the presence of his mother, an idealized (and loved) woman of his reality and of his dreams. All this functions in his universe as a lost paradise, one probably not “lost” entirely, but it certainly exists in a transposed universe of memory and poetry.

Gibran also is haunted by his childhood and early exile to America. At age 12 he returned to Lebanon where in Beirut, in the “Al Hikma” school which still exists today, he made a point of learning Arabic. Then Gibran lived in Paris, studied art, and returned to the United States settling, not in Boston, where the family had first established itself, but in New York.

Schehadeh also has a life between two major poles, after Alexandria: Beirut and Paris. He traveled for the rehearsals and then production of his plays in Paris. He traveled for a job at UNESCO, and then, during the Lebanese civil war, he moved to Paris, keeping the hope of returning to his country, which he loved. He loved Lebanon almost secretly, without the sentimentality that Lebanese usually demonstrate about their homeland. His profound attachment was in a way as indirect and as obliquely mentioned as the heart of his poems.

It seems to me that both writers encountered that peculiar form of exile which is not the lot of the political exile who cannot return to the country of his origin, but an existential and intellectual exile where one cannot rest anymore, where one always misses the “other” country. These exiles feeling a distance everywhere, without cure, because the borders are really open but the heart and the mind feel a restlessness which is at the end metaphysical, a permanent mystical experience. Thus, neither felt the need to anchor their works in a particular place but instead to make them exist, like the authors themselves, in a geography of their spirit.

ALIENATION THROUGH LANGUAGE

Language is usually a heritage, which is why we have the term "mother-tongue.” It roots us in a family, in an ancestry, and in the history of our country. Through it we appropriate to ourselves, to our intellectual and emotional self, the history and mythology associated with a particular place, that “place” being either reduced to a village or a city, or enlarged to a “country” or to a “world” (like we say “the Arab world”). This is why people usually write in their own language – not as a matter of convenience but for deeper reasons.

Gibran and Schehadeh did not write in what would have been their “mother-tongue.” Schehadeh wrote exclusively in French, and Gibran wrote his most essential work, his “message,” not in Arabic but in American-English, although he wrote also in Arabic.

Gibran’s case is fascinating in regard to the languages he used. Being exiled he made a point of studying Arabic and writing in Arabic. He co-founded a magazine in Arabic in New York, which made him, then, in the eyes of Americans, an ethnic Syrian. His audience was thus restricted, his “public” more “back home” than in America at large. Of course, “The Prophet,” a continuous best-seller in America, was written in English and translated into Arabic. This use of two languages while traditionally writers live in one language – the language of their own world/homeland – distances the writer from the meaning of language and makes language more relative; when a writer goes out of his own language, language becomes atool. Something is closed, is given up: the strong sense of belonging to a civilization through its language is lost. With the new adopted language, something else is opened, a new world becomes accessible, and a new adventure is born. What I just said is absolutely true for Schehadeh and for the “Francophone” Arab writers, or for all Arabs who choose to write in a foreign language. An essential contact is broken, missing, tragically absent. Hundreds of difficulties arise from this situation, and books can be written on them. It is a fascinating subject, and one which is more and more important in the contemporary world.

For people like Schehadeh and Gibran, this alienation manifests itself in strange ways. For Schehadeh it showed in the constant invention of nonexistent places and unusual names for his characters (like Bob’le’s name, or Locolina, Lieutenant Septembre, Ficelle, etc.). Their groundlessness gives them an air of unreality; they become dreamed people moving in a dream.

For Gibran it shows in the itching of languages and probably in the need to use a third language, which was for him the art of painting.

The most extraordinary result of this alienation in the works of both, is the resurgence of their “base,” their “home” (physical and spiritual), of their ancestral heritage, in their poems, plays, texts, and paintings. Everything they had to give up keeps coming to the surface like islands in an ocean. When you read Schehadeh, you hear Omar Khayyam more than Baudelaire; you attend one of his plays and you are in a Mediterranean country with no name and no special boundary, somewhere which starts in Alexandria and moves on. You read “The Prophet” and you know that Gibran read Nietzsche, but that he also went (even if not physically) to Jerusalem, and heard Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. You look at his paintings and you may think that William Blake or Rodin have had something to do with them, but then when you come close, you see the dramatic cliffs of the Kadisha, the blue-green-whitish light of the north of Lebanon, and the circle returns fully to its beginning! Their exile was probably painful at moments, their alienation was probably heart-breaking most of the time, but both exile and alienation became cleansing processes, but when all the surfaces are washed out and the essential core of their being – and their belonging – comes out with absolute clarity, there, in our mind, essential things find their place. You can call it Western Asia, the Mashreq, the other Orient, the Mediterranean East, the land of the three inseparable religions, the Origin of believers and unbelievers – whatever you call it, there is a “place,” both geographical and spiritual, from which Gibran and Schehadeh came, to which they belonged, and which constitutes the inner structure of their work.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 30, Winter 2000.

Copyright © 2000 AL JADID MAGAZINE