The Arab world lives in a state of nostalgia for bygone days, when much of the hatred and intolerance of today had not set in, and the demographic minorities of what was once called the Levant were not escaping to Europe and elsewhere. But the Levant of peaceful coexistence between religious and ethnic minorities and the Muslim majority has suffered a physical blow with the rise of the terroristic Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). While most of the world has been using the term ISIS, and major Arab media sources have subsequently reduced the name to The Islamic State, Obama and his State Department have delivered an additional moral blow by using the acronym ISIL (The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant).

Using the word Levant has raised much curiosity, both intellectual and political. Identifying the vicious and obscurantist ISIS movement with the region called the Levant, a place which historically has represented the polar opposite of ISIS ideology, causes dissonance. While watching Steve Kroft of CBS 60 Minutes’ interviewing president Obama, I could not help noticing that Kroft used the acronym ISIS while Obama used the term ISIL in his answers. It further begs the question: what and where is “The Levant?”

-1-

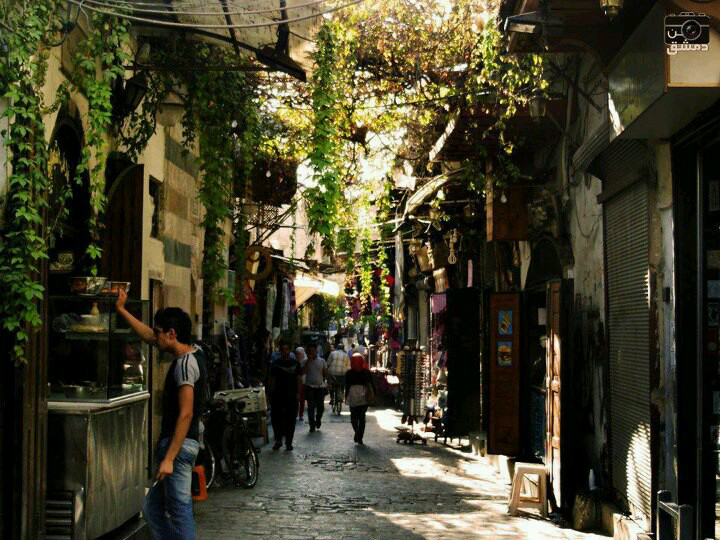

The term Levant refers to where “cultures met, borders blurred, and religions and people cross-bred for better or for worse,” according to Adina Hoffman’s review (“Writings from the Most Fractured Place on Earth”) of four Levant-related books in The Nation Magazine on August 27, 2015. The title of the review in the print issue of the Nation is “The L-Word.” Thus many question the wisdom of applying the “L-word” to ISIS when the Levant historically refers to what can be called a “melting pot,” with different groups living together although they come from different religious, linguistic and ethnic backgrounds. This practice directly opposes those of ISIS, from the beheading of captives to the smashing of ancient treasures and shared heritages in the name of a twisted version of Islam and a false Caliph.

Leaving aside the warped usage of the term, which has incurred the wrath of some scholars, including Ms. Hoffman, and ignoring for the moment the imprecise location of the Levant, the reviewed books highlight a range of examples. These range from pejorative references to the Levantines, as in the case of the early writings of the British Olivia Manning (1908–1980), to the more inclusive or all-embracing, if sometimes vacillating, inclusion of regional groups, Arabs and non-Arabs, Muslims and non-Muslims, as advocated in the writings of the Egyptian-Jewish Jacqueline Kahanoff (1917–1979).

-2-

The author of “The Levant Trilogy” and “The Balkan Trilogy,” Olivia Manning, used terms like “filth” (unless otherwise attributed, all direct and indirect quotes are from Ms. Adina Hoffman’s review) when describing Levantine Egyptians in the 1940s. Hoffman aptly calls these characterizations “orientalist” and goes even further in saying they sound “utterly squeamish and British.” Even as she left Egypt for other parts of the Levant, such as Damascus, Jerusalem, and Beirut, Manning’s attitudes towards the Levantines remained unchanged and consistent with earlier “colonialist” and orientalist literature. When she and Smith, her husband, moved to Jerusalem, where they lived for three years, she wrote an explicitly autobiographical essay describing her experience with a “profiteering Levantine population in Cairo,” which she termed an “unending nightmare.”

Manning’s views in the 70s concerning the Levant, as seen in her “The Levant Trilogy” contrasts with and reveals a transition from those views found in “The Balkan Trilogy,” which she wrote at a much earlier age. As Hoffman points out, “When, in the opening pages of the trilogy, an earnest young soldier enthuses to Harriet about everything the English have done for the Egyptians, she laughs at him: ‘What have we done for them?…I suppose a few rich Egyptians have got richer by supporting us, but the real people of the country, the peasants and the backstreet poor, are just as diseased, underfed and wretched as they ever were.’” This clearly contrasts with what the author wrote when a young novelist of 36 years of age.

-3-

The meaning of the Levant becomes clearer when the Nation article reaches the discussion of “Mongrels or Marvels: The Levantine Writings of Jacqueline Kahanoff (1917–1979), edited by Deborah A. Starr and Sasson Somekh. For those interested in the historical and political context of the term, Ms. Kahanoff, an Egyptian Jew, offers greater clarity and a more consistent view of the meaning of the term Levant.

Born in Egypt of Tunisian and Iraqi Jewish extraction, Kahanoff left the country of her birth in 1940 for the U.S. where she studied at New York's Columbia University. Afterwards, in 1954, she spent a brief period in Paris, and then left for Israel in the same year. There, she lived in a working class neighborhood, although it still maintained some aristocratic traditions and attitudes. Despite her strong familial links to the Levant, her command of both Hebrew and Arabic proved weak.

While still in Egypt, Kahanoff developed a great appreciation for the “civilizing powers” of Europeans, a position with which she gradually became disenchanted while in the United States, Paris, and Israel. Upon returning to Israel, she developed a realist appreciation of the idea of the Levantine as something beyond the binary extremes of Zionism and Islamism. Her own idealism led her to call for the Levant in which minorities historically played an important role. Thus her conception of the Levant “seems more important now than ever to,” imagining the region as a place “not exclusively Western or Eastern, Christian, Jewish, or Moslem.” In describing Levantines, she observed that whether Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, or Jews, though they speak different languages, they understand each other.

Kahanoff’s writing revives an important discourse either accidentally buried or deliberately overlooked in contemporary Arab and perhaps Israeli writings. She recalls Ben Gurion's warning of Israel becoming “Levantinized,” this from a man famous for his axiom of “us or them,” which carried clear political implications for the Palestinians. Some of the reverberations of his positions become evident in the bigoted, anti-Arab attitudes among the Israeli descendants of Eastern and Oriental Jews. What did Ben Gurion fear in Levantinization?

According to Kahanoff, “Levantinization” presented something positive to Eastern Jews, as the concept could bring them closer to their Arab neighbors and achieve what she described as “dynamically integrated relations with their surroundings.” In her idealism, she predicted that "Levantinization" would allocate power more equitably within Israel and integrate the country with its surroundings, meaning her Arab and non-Arab Levantine neighbors. Contrary to the Zionist ideal, Kahanoff attempted to reclaim that Levantine spirit, making Levantine a label to be proud of. She saw “no shame in mixing, crossing over, or in being in-between.” She believed this hybridization to be “Israel’s only hope.” She also added that “the Ashkenazi elite must stop projecting Israel as a bastion of Western enlightenment at the expense of wider Mideast expanse.”

Even as the world witnesses the flight of Assyrians, Kurds, Muslims, and Yazidis, Ms. Hoffman rehabilitates or glorifies Kahanoff’s predictions of the character of the region as neither Jewish nor Muslim, neither Zionist nor Arab, but rather Levantine.

Considering herself as an Eastern or Oriental Jew, Kahanoff believed Eastern Jews could serve as a bridge or model for natives of the region and the heirs to an older tradition of cultural symbiosis. While she articulated this idea in 1959, her ideas underwent subsequent development, something that became evident when she argued that “Oriental Jews suffered from internal colonialism, referring to domination and discrimination by Ashkenazi Jews.”

As time passed, Kahanoff's ideas devolved, becoming hopeless, especially in light of the deepening conflict between Israel and its neighbors. As Hoffman notes, “After 1967, she put forth disorienting and unsettling patronizing notions — for instance, about how Israel’s presence in the West Bank and Gaza might benefit Arab farmers by teaching them “new techniques of agricultural production.’” This idea closely echoes early Zionist ideas, which believed that while the Zionists busily converted the desert into a Garden of Eden, the land of Palestine remained agriculturally underdeveloped because of its population. Further, “she was not critical enough of Israel's control of the West Bank.” Although not a “card-carrying Zionist,” her views and those of the Israeli establishment appeared to come increasingly into alignment.

The article ends on a pessimistic note concerning the Levant and Kahanoff’s early vision of it: “The idea of Israel’s integration into a kind of open Middle Eastern union seems less likely now than ever.” This appears true for many reasons, not the least being the latest spate of clashes between Palestinian youth and Israeli soldiers and settlers, clashes which point to a potential third intifada.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 69, 2015.

Copyright © 2015 AL JADID MAGAZINE