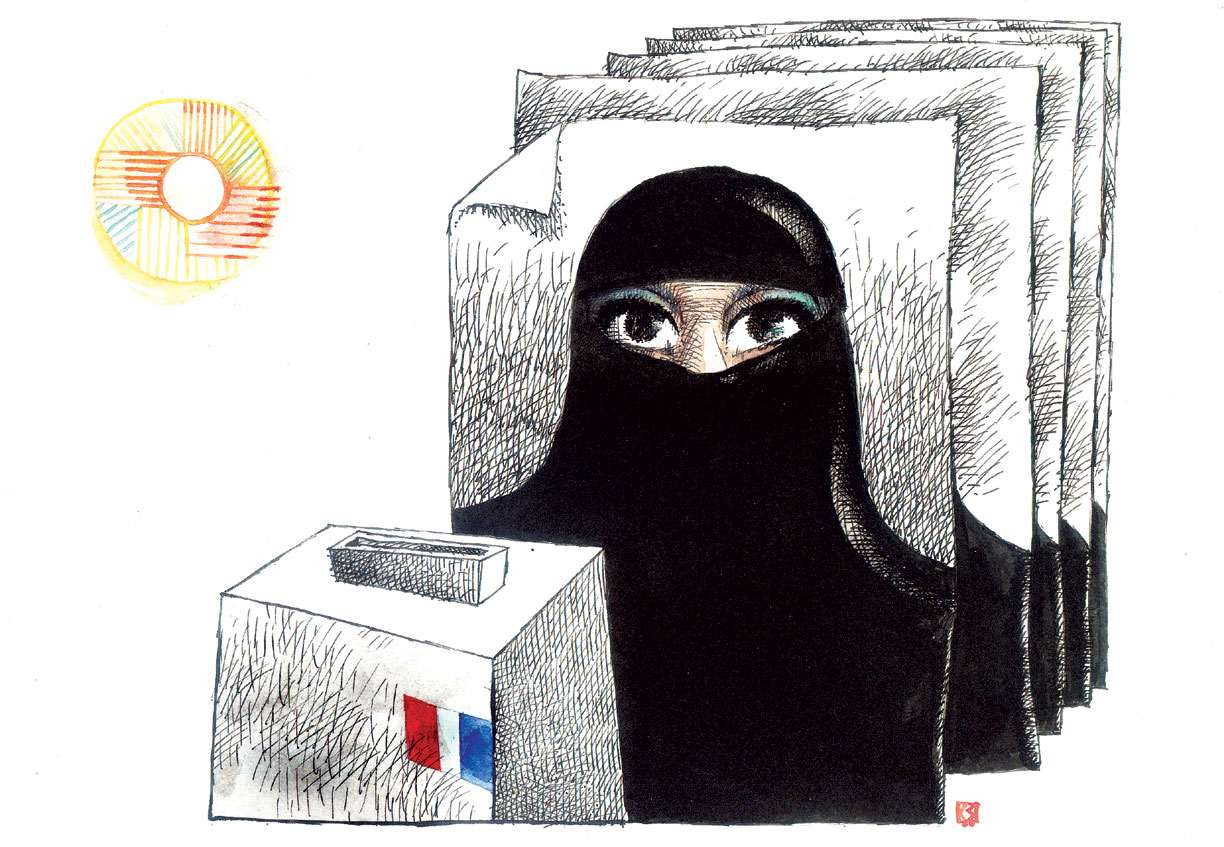

Many visitors to Damascus today are amazed to see how the practice of veiling has become so widespread, especially when compared to twenty or thirty years ago. It is as if the veil has imprinted the Syrian capital with its image. This is the case in the city’s streets and markets, its restaurants and parks, its schools and universities, its public offices and private companies, not to mention the homes that confine women within their walls in the name of the veil.

Indeed, a good many educated and enlightened thinkers in Damascus point to the renewed prevalence of veiling in order to illustrate both their powerlessness and the intensity of the conservative Islamic movement that their city is witnessing.

This article aims to bring to light some forgotten pages in the history of unveiling in Damascus and in the liberation movement of Damascene women. By elucidating some of the intellectual, social, and political factors that contributed to the movement toward unveiling in the first half of the twentieth century, the author hopes to explain some of the conditions that led to the reversal of this pattern from the 1970s onward.

While the forgotten pages in the history of unveiling discussed here are particular to the city of Damascus, they can just as easily be taken from the history books of any number of Eastern cities such as Beirut, Jerusalem, Baghdad, or Cairo.

It has become standard practice to date the launching of the movement in favor of Arab women’s unveiling and education to the publication of Qasim Amin’s book, “The Liberation of Women,” published in Cairo in 1899, and followed a year later by his book, “The New Woman.” Nonetheless, the true movement to unveil Arab women had to await the 1919 revolution and the famous women’s demonstration, led by Huda Shaarawi, to welcome back the exiled nationalist leader, Saad Zaghloul. There, Shaarawi and several other women demonstrators publicly removed their veils in the middle of the square. Zaghloul himself, upon his arrival, removed the veils from the faces of some of those who were there welcoming him.

In her book, “Veiling and Unveiling,” Natheera Zein al-Din quotes the literary writer, May Zeyadeh, who remarked of this incident in the Egyptian newspaper, “Al Ahram”: “Is there a more significant factor affecting women’s unveiling than the actions of the leader [Zaghloul] upon his appearance at the women’s congregation waiting there to welcome him? Indeed, his hand was faster than his mouth in expressing his wish, when, laughing, he reached over and removed the veil from the face of the woman demonstrator who was standing closest to him. His action was received with applause and ululations. The women there followed suit and took off their veils, signaling in that day, the liberation of women.”

By custom, religion, and practice, at that time, veiling was understood to mean the total covering of the woman’s body, including her face. Today, this form of covering is called “niqaab.” The call for unveiling by such as Qasim Amin and Huda Shaarawi at first only referred to removing the veil from women’s faces and allowing them to leave their homes. Nonetheless, their efforts contributed to relaxing the rigid, orthodox view of the veil, and removed social and religious taboos with regard to unveiling. Their actions also exposed the lack of validity in the excuses and religious sayings that were used to perpetuate the practice of veiling up till then. Those actions also paved the way toward the eventual removal of the veil completely from women’s heads. While this latter development took several years to occur, it was nonetheless a natural outcome of the path that had been opened up by Qasim Amin.

Egypt, at the time, was at the forefront [of Arab countries] in the movement toward women’s liberation. Egyptian women made the transition from words to deeds. In an article published in 1928 in “Hillal” magazine, Sheikh Ali Abd al-Razzaq remarked: “I consider Egypt to have made the transition, with God’s blessing, from the conceptual considerations of veiling to the actual implementation of unveiling. Among Egyptians, except for retrogrades, you can no longer find those who question whether unveiling is permissible by religion or not, or whether it is one of the necessities of modern life or not. Rather, even those who are still old-fashioned and veiled believe that unveiling is in accord with religion, reason, and necessity, something that cannot be avoided in a modern city.” Abd al-Razzaq adds, “Our brethren in Syria seem to have a different history to veiling and unveiling than in Egypt. For they seem not to have yet gone beyond the conceptual stage that was begun by the late Qasim Amin twenty years ago. Nonetheless, they seem to walk beside us along this new path, the way of actual, total unveiling.”

Veiling in Damascus

In Damascus, it appears that there were only a handful of scattered writings toward the end of the nineteenth century in favor of women’s unveiling. These were penned by such writers as Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq and Zeinab Fawaz al-Amiliya. In fact, no complete work along the lines written by Qasim Amin appeared in Syria until the publication of a book by Nazira Zain al-Din [published ca. 1928].

|

| "A domestic/servant offering a narghileh" by Jean-Baptiste Charlier, ca 1867 from "Des Phographes a Damas 1840-1918" by Badr El-Hage, Marval 2000. |

In Damascus, the catalyst that encouraged women to lift the veil from their faces in public for the first time was a national event that was equal in significance to the return of the exiled Egyptian nationalist leader Saad Zaghloul. This event, however, was of a different type from the one that occurred in Egypt. It took place when the American ambassador Charles Crane visited Syria in April 1922. Crane was sympathetic to the Syrian demands for independence from France and he was a supporter of the Syrian nationalist leader, Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar. Shahbandar was known for his calls for the liberation and education of women. He, along with other nationalist leaders, was arrested for participating in public demonstrations welcoming Crane and calling for Syrian independence. These arrests led to more demonstrations among the general public. For the first time in the history of the city, women began participating in public demonstrations, and some even took off their veils.

In his book, “Syria and the French Mandate,” the historian Philip Khoury writes: “On April 11th, organizers added a new approach to their demonstrations, positioning forty women at the head of their long march, among them the wife of Shahbandar as well as other wives of imprisoned nationalists.”

Upper class women such as the wife of Shahbandar, Sara al-Mouayed al-Azem, and other wives of nationalist leaders were in the forefront of those who took off their veils in public. However, the matter was much more difficult for less privileged Damascene women. In fact, prevailing custom put pressure on Muslim women to remain fully veiled in public up until the 1920s. For some girls, leaving the home to go to the marketplace was an act that put their lives in danger.

In 1927, a group of Damascene women, foremost among them the feminist pioneer Thuraya al-Hafiz, organized a demonstration at Marja Square, during which they lifted the veils from their faces. The matter of veiling was not so easily settled however. As Nazira Zain al-Din points out in the preface to her book on women’s rights and unveiling, the reason why she felt compelled to write in the first place was the unrelenting pressures that were placed on Damascene women to stay veiled. She notes: “I began to study the position of Eastern women as soon as I began to understand the meaning of justice, liberty, free-will, self-reliance, and the insufficiency, even inadmissibility, of tradition in God’s religion. I found much that was strange and saddening to me. I held back a great deal, but the events in Damascus last month, when Muslim women’s freedom was suppressed and they were forbidden from leaving their homes to enjoy the air and light, drove me to take up the pen to express an abbreviated version of the pain I feel.”

Up until the end of Ottoman rule in the early decades of the twentieth century, veiling in Damascus had remained a social practice that required not only the complete covering of a Muslim woman’s face, but also of her full body. This practice also entailed sequestering women in the home, forbidding them from obtaining an education, and arranging for them to marry at an early age. In his book, “The Damascene Woman,” Abd al-Aziz al-Hithma describes the situation of women at the time. “When women went out of doors, they would wrap themselves in a white veil that reached to their feet and would cover their faces in colorful scarves that prevented others from seeing anything behind them. Enveloped in modesty and respectability, no one dared approach them, even if they were related to them, because for men to talk to women in the marketplace was deemed shameful.”

Women at that time were completely denied the right to education and forbidden from leaving the home alone. Religious men, who controlled the educational system until late in the nineteenth century, taught boys only. Their curriculum consisted of a series of “booklets” that taught the Arabic language and the fundamentals of religion. Up until the beginning of the twentieth century, there was only one high school for boys of elite families in Damascus. Its language of instruction was Turkish and it prepared boys to pursue higher education in Istanbul.

Upon the end of Ottoman rule, however, a series of fast-paced changes overtook the country. Those occurred at the political, economic, and social levels. The ideas of the Arab Renaissance and calls for educational reforms spread among the educated classes through important reformists such as Sheikh Taher al-Jazzairi, Sheikh Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi, and Muhammad Kurd Ali. The changes proposed by these thinkers paved the way toward more modern political, social, and cultural practices in the new neighborhoods of the city. These changes also led to a decrease in the influence of conservative religious figures on social conduct. Little by little, it became possible for girls to be free of veiling and to enter schools and universities, and so to assume their place in the public sphere.

The Unveiling of the City

The issue of women’s liberation became one of the principal points of social controversy during this new phase of social openness, becoming one of the main topics of public debate in newspaper articles. This debate was accompanied by noticeable changes in the position and role that women came to occupy in the public sphere.

The practices of unveiling, mixing of the genders, and the imitation of European lifestyles were at first limited to the privileged classes of Damascene [Muslim] society (in particular the family clans of al-Azem and al-Abid) and a few Christian women. This phenomenon, however, soon began to spread among large segments of the educated and the professionals of the middle class. While this new lifestyle was no longer limited to a particular class, its adoption was still somewhat circumscribed, remaining most prevalent among the young girls and students in the newer neighborhoods and a few upper class women. An article titled “The Syrian Girl Today,” published in the newspaper “Al-Sabah” on January 22, 1934, clearly describes the changes taking place: “The new spirit of modernism has arisen in the Syrian capital to such a point that you can walk in the streets of Damascus and witness many young women wearing Western clothes in bright colors, eschewing their old clothes, and walking on the street with male friends. This is something that was simply unheard of before our time.”

|

"A woman smoking the narghileh" by Jean-Baptiste Charlier, ca 1867 from "Des Phographes a Damas 1840-1918" by Badr El-Hage, Marval 2000. |

As this new lifestyle began to spread to wider segments of society, it met resistance and even violent rejection by religious authorities and notable personalities in certain populist areas such as Hay al-Meydan. In his book, “Syria and the French Mandate,” the historian Philip Khoury points out that the religious organizations that were formed in the period between the two world wars made it a point to urge the general public to focus on two controversial matters: women’s place in society and the educational curriculum. As Khoury also points out, this time period was witnessing great changes in lifestyles and social conduct. Greater opportunities for travel between the Middle East and Europe as well as the gradual spread of modern, secular education during the mandate period provided new opportunities for women from the upper and upper-middle classes. Women began to adopt new forms of dress and came to hold new aspirations that distinguished them not only from women among the general masses but also from their mothers and grandmothers. According to Khoury, the changes that were occurring in the period between the two world wars helped women to venture into the public sphere more than before. The wives and daughters of nationalists, in particular, took on more active roles in the political arena, participating in demonstrations and working with charity organizations. Little by little, these greater levels of participation pushed the question of women’s rights to the surface.

Syria’s former prime minister, Khaled al-Azem (1903-1965), remarks in his memoirs on the changes that occurred in women’s clothing in Damascus during the twentieth century. He says: “The main difference between the past and today is to be seen in women’s dress. Women, the poor things, had to wrap themselves in a full-length black veil that completely hid the form of their bodies. Their faces were so covered that they could barely see the light. I am inclined to erect a statue to that Arab Muslim woman who could walk in the street and see her way through that type of veil.” Al-Azem, who received the highest proportion of votes in the parliamentary elections that occurred during the democratic phase [of Syrian history], describes the progress that women had made in their manner of dress. He situates this change in the context of historical progress and the change in the social status of women, regardless of where they lived, whether in the newer or the more traditional neighborhoods of the city. He notes: “Even though women in the city’s old sectors continue to wear traditional clothing, the social status of residents in the newer sections have changed. There, the full wrap was first exchanged for a shorter one that barely reached the knees and exposed arms and hands. The face veil became thinner and thinner until it became so transparent that it only covered some blemishes, thereby enhancing the beauty of the face rather than concealing it. Women took an even braver step when they exchanged the wrap with a thin head covering, the “yashmak,” and wore regular clothes covered by a coat. In the end, modern women eschewed all signs of outdoor dress that would distinguish them from non-Muslims.”

Inevitably, the fast-paced changes in women’s dress were met, from time to time, with resistance and public demonstrations by religious organizations that viewed them as signs of the undermining and decline of traditional Muslim customs in society. As Philip Khoury points out, in May 1942, religious organizations led demonstrations “denouncing women who would venture unveiled to public spaces, take walks while hanging on to their husbands’ arms, or go to the movie theaters. They demanded that the government dedicate special tramway cars during rush hour in order to segregate the sexes and that it close down all taverns and nightclubs located near religious or cultural centers. They also demanded that a new morality police division be created with the express purpose of eradicating vice.” As Khoury also notes, however, the government of Husni al-Barazi, along with a few other religious authorities, paid no heed to these demonstrations. Furthermore, Khoury points out that students from “Tahjir” school, who were active politically in the city, took a position that strongly opposed such demands, ultimately leading to the failure of the [conservative] movement.

In May 1944, major clashes took place between conservative religious groups and prominent figures such as the prime minister Saad-allah al-Jabiri in the nationalist movement. The clashes came in the wake of an incident that came to be known as the “Drop of Milk” (“niqtat al-haleeb”), the name of a women’s charity organization that was headed by the wife of the minister of education, Nusooh al-Bukhari, and that included a number of wives of prominent nationalist politicians. The Drop of Milk organization had planned a charity dance event. What upset the religious conservatives was the news that Muslim women would be attending this event unveiled. Consequently, they organized angry protests and set upon certain cinemas, forcing women to leave the theaters. Four people were killed in the ensuing violence that erupted in Hay al-Meydan.

It is important to note that in Arab countries at the beginning of the twentieth century, intellectual debates regarding women’s dress separated the question of veiling from religion. Unveiling was not accompanied by a repudiation of Islamic principles. On the contrary, changes in women’s dress were taking place at the hands of Muslim women who were proud of their identity as open-minded Muslim believers. The question of the veil was regarded among the educated classes as an issue that was tied to individual freedom and women’s personal choice as well as with progress. It was seen as having no relationship at all to religious commands and obligations.

Muhammad Kurd Ali, one of the leaders of the “Arab Awakening” movement, commented in his memoirs, published in 1951: “We are wary of resorting to force in doing away with the veil lest we create an opportunity that the conservatives can exploit. As far as I see, the practice of veiling is weakening of itself. Its use is limited in the countryside, and it is being used less and less with each year in the city. Many female students now leave the house unveiled and do not wish to return to veiling after finally being rid of such a practice. They are even encouraging their mothers and families to follow their example and bare their faces.”

It is thus impossible to look at the phenomenon of women’s unveiling in Damascus as something separate from the intellectual, political, and social atmosphere that was current at the time. This was an environment that was essentially concerned with freedom. It is true that the 1940s and 1950s were afflicted by a series of military coups and the temporary suspension of political freedom. Nonetheless, there were no attempts to infringe upon the social framework, to choke social freedoms, or to take hold of civil institutions. The efforts to modernize and the understanding of modernity were concomitant to a social dynamic that championed development, openness, and hope in the future.

The Backlash

Damascus was a city that took the Arab nationalist cause to its ultimate conclusion. Its populace, both men and women, took to the streets in 1958, calling for unification with Gamal Abd al-Nasser’s Egypt. Yet this same city witnessed its nationalist dreams dissipate in the wake of the military coups that were linked to Arab nationalism. Damascus soon saw its political and cultural diversity dissolve into the confines of single party rule. It witnessed its burgeoning social openness close off in response to the failed efforts at modernization. While the city had been in the process of lifting the veil from itself, it returned to shrouding itself in a political veil, abandoning the movement toward intellectual awakening. In the process, Damascus transformed itself from a city full of promise to a small town untouched by progress.

In trying to account for this reversal, some blame the resounding Arab defeat in the 1967 war with Israel along with the failure of the state’s modernizing agenda. Others point to Islamic revivalism and the Iranian Revolution. Yet others fault the oil boom and Wahhabist thinking.

In truth, I do not know the reason, but it seems that nothing explains how broken and humiliated the city had become with regard to the question of veiling as much as the tragic events that took place on its streets in 1981. At that time, Rifaat al-Assad [head of special forces, Saraya al-Difaa, or “Defense Companies”] had decided, without prior warning, to send certain undercover women in the company of the armed members of Saraya al-Difaa to the streets of Damascus in order to force all women, regardless of their age, to publicly remove their veils, imposing a ban on veiling in the streets.

This order was rescinded on the following day by authorities representing the Syrian president Hafez al-Assad, restricting the ban on veiling to students within the confines of their schools. Later, this ban too was lifted at the beginning of Bashar al-Assad’s rule [in 2001].

Nonetheless, the momentous events of 1981 removed the question of veiling entirely from the realm of personal freedom and placed it squarely into the realm of politics and political identity.

The state’s authority was strengthened in the aftermath of its devastating clashes with the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1980s. The price of armed confrontation with militant Islam was the dismantling of civic freedom. At the same time, some religious teachers whose families were descendants of Sufis … were allowed to become active in Damascus, to expand their circle of followers, and to form associations and institutes. These religious figures advocated a particular understanding of Islam, which outwardly appeared far removed from politics but which was nonetheless extremist and regressive in its social and cultural outlook.

In Damascus today there are thousands of mosques that are overseen by the office of the mufti (dar al-ifta’), and there are numerous schools for memorizing the Quran. Moreover, there are about fifty thousand university students in Damascus. Of those, about nine thousand attend a sharia college.

The Syrian government has chosen to look the other way with regard to these religious institutes, neither banning nor recognizing them. With time, these institutes have developed into colleges, and those colleges into universities that grant degrees, even doctorates. This is all happening at a time when the government still refuses to grant permission not only for the formation of political organizations but also for any intellectual or cultural activities that do not fall under its direct supervision.

In addition to the flourishing of religious schools, the city of Damascus has also witnessed the phenomenal rise of “al-Qubaysiat,” an old, women-only Sufi order that was founded by the Damascene lady, Munira al-Qubaysi. This movement originally spread among the more socially and economically privileged classes. Initially, it undertook to mold the character of urban women and to encourage them to wear the veil. Religious instruction was provided in the homes, and, on occasion, the lessons were accompanied by celebrations of religious occasions. Ibrahim Hamidi, a reporter to the Damascus newspaper, “Al-Hayat,” estimates that this movement has a following of about seventy-five thousand girls. He also estimates that about forty religious schools revolve around the teachings of Sheikha Munira al-Qubaysi. These schools offer the official curriculum of Syrian schools in addition to providing religious instruction. (“Al-Hayat” 5-3-2006).

What is shocking about all this is that the religious figures today have surpassed their predecessors in their conservatism and closed-mindedness, succeeding in areas where their forefathers had failed in the 1920s and 1930s. This is especially true with regard to their opposition to women’s unveiling, education, and freedom to leave their homes. Religious figures today not only receive protection and financing from the state in their efforts to spread their conservative views (as is their right), but they also incite the government to strike with an iron fist anyone who dares open a window to let intellectual enlightenment shine upon Damascus.

Suffice it to say that a century after the publication of Qasim Amin’s book, “The Liberation of Women,” in Cairo, two figures who are ever present on the airwaves of Radio Damascus and on Syrian television, Sheikh Muhammad Said Ramadan al-Bouti and Sheikh Muhammad Ratib al-Nabulsi, still declare fatwas declaring that the most becoming, prudent and safe way for Muslim women to conduct themselves is to hide their faces and remain veiled. This is all taking place at the same time as the incarceration of the opposition leader [and democracy advocate], Dr. Fida al-Hourani, who remains unveiled but jailed in the women’s prison in Douma.

The reason why Dr. al-Hourani was put in prison is simple and can be found in the fatwas of both Sheikh al-Bouti and Sheikh al-Nabulsi. With regard to democracy, al-Bouty says: “If you mean by democracy that there should be consultation between those in authority and members of the general population, then this is a principal aspect of state government in Islam. However, if you mean that the people should rule themselves, then this is contrary to the rule of Islam, because the ruler in Islamic Sharia is God.” Al-Bouti, on the other hand, voices his opinion in a frank but harsh simplicity, “Democracy is foreign to Islam.”

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 16, No. 62, 2010.

Copyright © 2010 AL JADID MAGAZINE