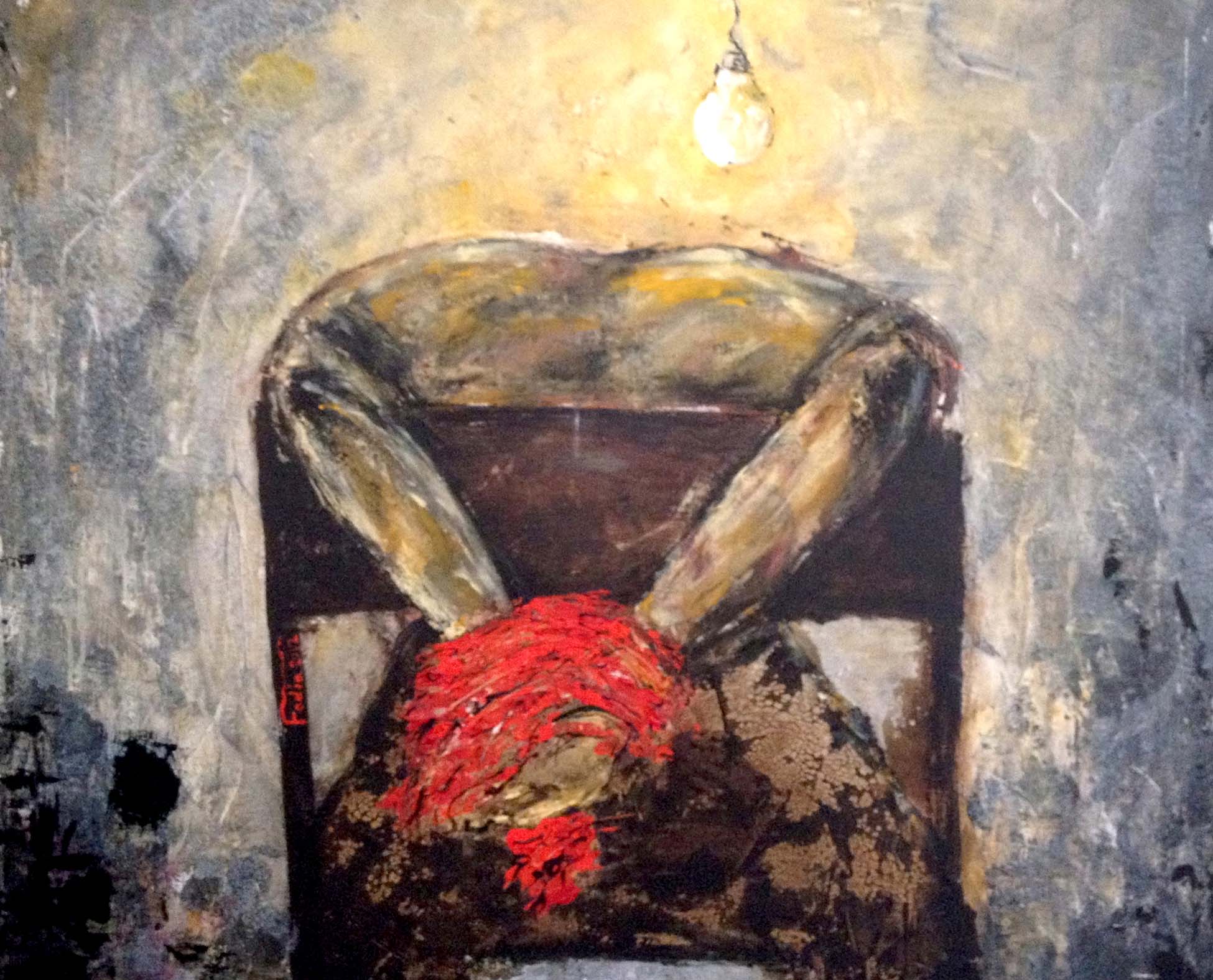

“The Interrogation” by Fadia Afashe. This image also appeared as the cover artwork for Al Jadid Vol. 17, No. 64, 2011.

Arabic literature is perhaps one of very few literary traditions that have a distinct literary genre known as the "prison novel." This is not only because a great majority of writers have themselves lived the experience of arrest, imprisonment, and even torture, but also because the history of the contemporary Arab intellectual is one of constant struggle with the authorities. The colonial authorities and their local cronies were succeeded after independence by national authorities who in many regions of the Arab world have surpassed their predecessors in the various methods of tyranny and oppression. Thus, imprisonment and torture and even political assassination became important topics in the Arab novel. Even a writer like Naguib Mahfouz, who was one of the few Arab writers who did not experience imprisonment and political persecution, includes such topics in many of his novels. However, Mahfouz's novel that most directly addresses the tragedy of the absence of freedom and the devastating effects that the deprivation of the Egyptian individual's basic rights had on the entire nation is the novel "Al-Karnak" (1974). This novel demonstrates the ghastliness of the political prison camps and the torture and devastation that befalls the simple, ordinary individuals, and the deep and bloody scars that these leave not only on the body of the victim but also on the souls of both the victim and the custodian. The novel is a direct outcry against the imprisonment of those who cared for their country – a strong protest against the torture of those who are innocent of any crime except for love of their country and the courage to defend its aspirations and to dream of a just and better future.

Some of the most prominent and bitter experiences of political imprisonment in the Arab novel include "Al-Sijn" (The Prison, 1972) by the Syrian writer Nabil Suleyman, and "Thuna'iyyat al-Sijn wa al-Ghurba" (The Duet of Prison and Alienation, 1995) by the Egyptian writer Fathi Abdul Fattah. The latter links the bitter and difficult experience of political imprisonment to the experience of exile and the atmosphere of persecution that dominated Egypt in the 1970s. This persecution forced many to migrate by making it difficult for them to live a decent life in their own country; most of their rights had been violated and destroyed. "Al-Aqdam al-'Aariya" (Bare Feet, 1980) by Taher Abdul Hamkim recounts his bloody ordeal that lasted five years (1959-1964) in Al-Wahat (Oases) prison camp. Mustafa Teeba's "Rasa'il Sajeen Siyasi Ila Habibatihi" (Letters from a Political Prisoner to His Beloved, 1977) recounts a similar experience through the medium of letters, revealing the political prisoner's isolation and the ugliness of the prison experience. Its effects not only enervate the body and soul of the prisoner himself, who suffers because of his political views, but also devastates the life of his family and friends on the outside where human freedom is being violated. Teeba explores the implications this has for his own inner prison. Fu'ad Hijazi's novel, "Sujanaa' Li Kul el-'Usour" (Prisoners for All Ages, 1987), documents his bitter imprisonment and persecution in his hometown of al-Mansoura because of his political beliefs. He was imprisoned and deprived of his human rights for his political views, and his writing was also subjected to censorship and confiscation.

Accounts/Testimonies

One should not overlook Ilham Sayf al-Nasr's significant experience "Mu'taqal Abou Za'bal" (Abou Za'bal Prison Camp, 1978) which documents the horrible events that took place there in 1959. Many political detainees died as a result of gruesome torture after their basic human rights had been violated both physically, psychologically, and mentally. These incidents are among the most terrible examples of imprisonment, torture, and human rights violations in Egypt's recent history. They also inspired one of the most important prison novels in Arabic literature, for one of those killed in this horrible prison was Shahdi Atiyya al-Shafi. Fathi Ghanem documents the ordeal of this famous leftist revolutionary and historian, and his subsequent death in this prison, in his beautiful novel "Hikayat Tu" (The Story of Tu, 1987). The structure of this novel deserves mention for it recounts the events through a series of recollections, reminiscences, and cross-references. It makes the events in this notorious prison appear as an experience that had been engraved in the recent history of Egypt and that had left its mark upon its conscience. In "Mudhakkarat Fi Sijn el-Nisaa" (Memoirs in a Women's Prison, 1986) Nawal al-Saadawi recounts the story of her imprisonment with more than 1,600 writers and politicians, a round-up ordered by Sadat one month before his assassination. The same events were also captured in a more artistic and sensitive manner by the great writer Latifa al-Zayyat in her remarkable book, "Hamlat Tafteesh: Awraq Shakhsiyyah" (An Inspection Campaign: Personal Papers, 1992). In the tradition of Zayyat, Salwa Bakr's novel, "Al-'Arabah al-Dhahabiyyah la Tas'ad ila al-Sama" (The Golden Chariot does not Ascend to Heaven, 1991), elevated the experience to the level of potent metaphor for the condition of women in society. Several other contemporary works appeared in the 1990s, such as Shareef Hattata's "Al-Nawafidh al-Maftouha" (Open Windows, 1995) and Fathi Fadhl's testimony, "Al-Zanzana" (The Cell, 1993). The latter recounts experiences that took place in the 1990s following Fadhl's arrest on the false charge that he had published the book entitled "Masafa Fi Aql Rajul: Aw Muhakamat Ilah" (Distance in a Man's Mind: or A God's Trial). The mistaken book, written by Alaa' Hamed, created an outburst of controversy and legal action following its confiscation on the charges of tastelessness and offensiveness towards religious believers. "Al-Zanzana" presents the events in a mixture of narrative and documentary styles describing what takes place in the arrests and corrupt prison system of the 1990s. Finally, there is the most recent and perhaps the most important novel of this genre, namely Sunallah Ibrahim's "Sharaf" (1997).

The Colonial Period and Political Assassination

The prison novel, however, has its roots long ago during the colonial period. Ihsan Abdul Quddous' novel "Fi Baytina Rajul" (A Man in Our House, 1957) takes place in the 1940s and tells the story of Ibrahim Hamdi, a nationalist fighter who escapes from the hospital following his brutal torture in prison. The novel is darkened by a backdrop of political assassinations of British agents and the torture and arrest of nationalists, such as Ismail Sidqi and Ibrahim Abdulhadi, in the prisons of puppet governments. The protagonist of the novel is accused of assassinating Abdulfattah Pasha Shukri, who is a politician and an agent of the British. Hence, the family hiding the protagonist does not look upon him as a criminal, but rather as a simple patriot who wanted to defend his country against colonialism. Prior to independence, political assassination was associated with the struggle for national independence and freedom. The clear separation between the patriotic self and the colonial other made it easier for the writer to establish the character's stance towards these horrible occurrences that would justify killing an individual. Similarly, Yusuf Idris' "Qissat Hubb" (Love Story, 1956) raises the same issue of the predicament of those who fight to liberate their country from colonial rule at the hands of puppet and corrupt governments. The people, en masse, see these governments as illegitimate and part of the oppressive apparatus of hegemony and colonialism, and their attackers as national heroes worthy of support and protection.

In many works of fiction the prison theme is closely linked to that of political assassination, which in turn is linked on many levels to the issues of freedom, and national and human rights. Many Arab writers became preoccupied with these complex issues in the early years following independence. The two novels "Jeel al-Qadar" (Destiny's Generation, 1961) and "Tha'ir Muhtarif" (A Professional Revolutionary, 1962) by Syrian writer Muta Safadi address the issues of political freedom and assassination although his approach is more existential than purely political and social, unlike other Arab writers. "Jeel el-Qadar" presents the question of freedom and the human rights that ensue from it by intertwining the protagonist's existential freedom and his desire for individual growth, although this personal quest is challenged by the state of affairs in the Arab world. For example, when their organization fails to assassinate the dictator, the characters in the novel believe that their failure was due to an absurd coincidence that saved the dictator's life. Their enthusiasm to assassinate the dictator does not seem to spring from their rejection of his tyranny and their wish to eliminate his non-democratic policies, but rather emerges from a lustful desire for self-fulfillment. The characters are unaware of the underlying contradictions, which become apparent in the way the story evolves and leads to the unsuccessful assassination attempt. They land in the throes of terrible confusion which rises primarily from a violent sense of personal failure. One character leaves for Aleppo while another goes to Algeria, retaining the same problematic understanding of freedom and the desire to fight for it, using the same approach as before. Thus, while in a land whose sons are dying to liberate it from a vicious colonial occupation, he screams: "I hate for any one of us to die for the sake of the peoples of Algeria, Iraq, or Syria. Arabs die today because it is their destiny." This existential view of freedom, although it differs from the social or political ones, still emphasizes the importance of freedom as an essential human right, and this work demonstrates the bloody consequences of its absence in the Arab world.

Safadi's novel is not unique in this regard. Many Arab novels opted to address the question of freedom and its absence in the Arab world more from an existential standpoint than a social or political one. One of these novels is Suhail Idriss' "Asabi'una Allati Tahtariq" (Our Burning Fingers, 1962), which presents this issue through the agonizing struggle of the two protagonists, Sami and Karim al-Hadi, who waffle between the certainty of their commitment from an intellectual standpoint and their aversion to this commitment from a political standpoint. Hence, their excessive confidence in the power of their words and in the spontaneous commitment they made thanks to a turn of events is not sufficient to explore all aspects of the issue of freedom. The novel attempts to present the issue of freedom on a scope larger than that of contemporary Arab affairs. Abdulsalam Ujayli's "Bassima Bayn al-Domou" (Bassima Amid the Tears, 1959) also explores freedom by portraying the intense life that the protagonist Suleyman experiences and his severe conflict between his physical relationship with Bassima and his platonic love for Ilham. He convinces himself that he has earned the right to pursue his personal relationships by performing his duties to his country, writing his passionate newspaper editorials on freedom and making many speeches in his political party meetings. He neglects to take into account the continuous interaction between the lack of social freedom and the freedom of each individual in that society, and personally encounters the ramifications of this interaction throughout the novel while thinking that he is practicing his individual freedom in love.

The attitude towards the subject of freedom in the Syrian novel changed with the generation of novelists that followed. Noteworthy is the evolution that the works of two important Syrian novelists, Khayri al-Dhahabi and Nabil Suleyman, produced as each addressed the issues of freedom, prison, and political oppression in his own way. Both link these issues with the social and political history of Syria and with the many cultural changes that took place over half a century through the fight for independence and the contradictory tribulations following independence. Al-Dhahabi's important trilogy, "Al-Tahawwulat: Haseeba, Fayyad, and Hisham" (Changes: Haseebaa, 1987, Fayyad, 1990, and Hisham, 1995) is an ambitious epic novel that attempts to address the issue of freedom in its broad sense as it had evolved through the human rights movements both on the liberal and socialist levels. The novels open with the great Syrian rebellion against the French occupation and proceed to describe how the merchant class disarmed the rebels and emptied the slogans for independence from their significant content before recognizing them. They elaborate the different facets of the rich social reality of the old city in a very intelligent manner, intertwining the private aspects with the public ones, the merchant class and the dynamic of its development with the historical, and the day-to-day with the eternal. The story takes place over three generations, representing the lives of the three characters for whom the different parts of the trilogy were named, also paralleling the progress of Syrian history which in turn represents the struggle for human rights in various Arab countries. The epic also tries to capture the collective memory in the folds of its text, coloring this with the painful quest of the Syrian individual for his freedom and the high price he pays for this by imprisonment, torture, and exile.

It is more difficult to cover Nabil Suleyman's work, even his most important works, in this study because of the magnitude of his writings. One must, however, mention at least his epic quartet, "Madarat al-Sharq" (Eastern Tropics, 1990-1993) because this novel uses Syrian history as its backdrop (or sphere) and documents the social, historical, and political changes that took place in Syrian society over a period of a century. It spans the turbulent times from the departure of the Turks to the advent of the French to the present. It is an epic novel in every sense, for its narrative covers extensively all aspects of human rights that ensue from the question of freedom: social, economic, political, and individual. This novel is not a documentation of history but rather a means to encourage contemporary awareness of the tribulation suffered by the Syrians, and by extension all Arabs, in this long historical process. The novel also uses history as a vehicle for plot development, as characters continually change and become minor tyrants themselves while innocent people suffer the harassment and manipulation of the opportunists. The prison doors, from the Qal'a prison to al-Qamishly and from the Aleppo prison to Salkhad, open their doors to seize the freedom of individuals while at the same time intensifying the struggle for their rights. The novel mixes reality with fantasy and history with fiction to create an epic of man's continuous and arduous struggle for his basic and legitimate rights.

Other Important Novels

Before ending this discussion – which could go on at length – about the experiences of oppression, imprisonment, and the deprivation of man's basic rights and freedom, one needs to mention four important novels. These are Fathi Ghanem's "Hikayat Tu," Sunallah Ibrahim's "Sharaf," Yusuf al-Sayegh's "Al-Sirdab Raqm 2" (Tunnel Number 2, 1997), and Turki al-Hamad's trilogy "Atyaf al-Aziqqa al-Mahjura" (Shadows of Deserted Alleys: 'Addama, 1994, Shimaisi, 1995 and Karadeeb, 1996). The first novel depicts in beautiful and skillful narrative the experience of prison in 1950s Egypt, while the second presents the same experience in 1990s Egypt with a unique and captivating mix of fictional and documentary styles. From these two novels we observe that the Arab individual has not learned from his mistakes and that the deprivation of his rights in the 50s was much easier than his prison experiences – horrible prisons filled with brutality and corruption – in the 90s. Yusuf al-Sayegh's novel describes the political prison experience in Iraq, something we hear much about although no one has before written about it in such frightening detail. He gives us new insight into the horrible experience of political detainees and the inner life of the prison wing devoted to them.

Al-Hamad's epic takes us to Saudi Arabia and devotes the last part of the trilogy to the political prison that gives the novel its name, "Al-Karadeeb." Following in the tradition of Naguib Mahfouz, who called the three parts of his monumental Cairo Trilogy after street names in heart of Cairo, Hamad chooses names of three places for his. The first, "Al-Addama," is a name of a popular quarter of Dammam in the eastern part of the country. The second, "Al-Shimaisi," is named after a similar quarter in Riyadh, while the third, "Al-Karadeeb," takes its name from the dreaded political prison outside Jeddah. The third novel's 300 pages are an account of the protagonist's years in this notorious place and the torture, physical and psychological, that he endured. Although the experience it depicts has many common features with those narrated in other novels, the structure of the trilogy gives it added significance. The trilogy devotes its first novel to the cultural and political formation of its heroes, and the second part to the protagonist's discovery of the sexual world and his interaction with love, women, and sex. The complete devotion of the third novel to the political prison and its cruel remolding and reconditioning of the individual makes a profound statement about the Saudi establishment and its country. If education and sexuality are two essential parts of the formation of the individual in this country, the servitude, humiliation, and subjugation are also essential for shaping the conformist individual and preserving the regressive continuity of the Saudi establishment. The third novel also makes a vital link between the ostensible, but empty, modernization of the country and the suppression of human rights, as if one is dependent on the other, or even necessary for its manifestation.

Translated from the Arabic by Basil Samara.

This essay appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 38, Winter 2002.

Copyright © 2024 AL JADID MAGAZINE