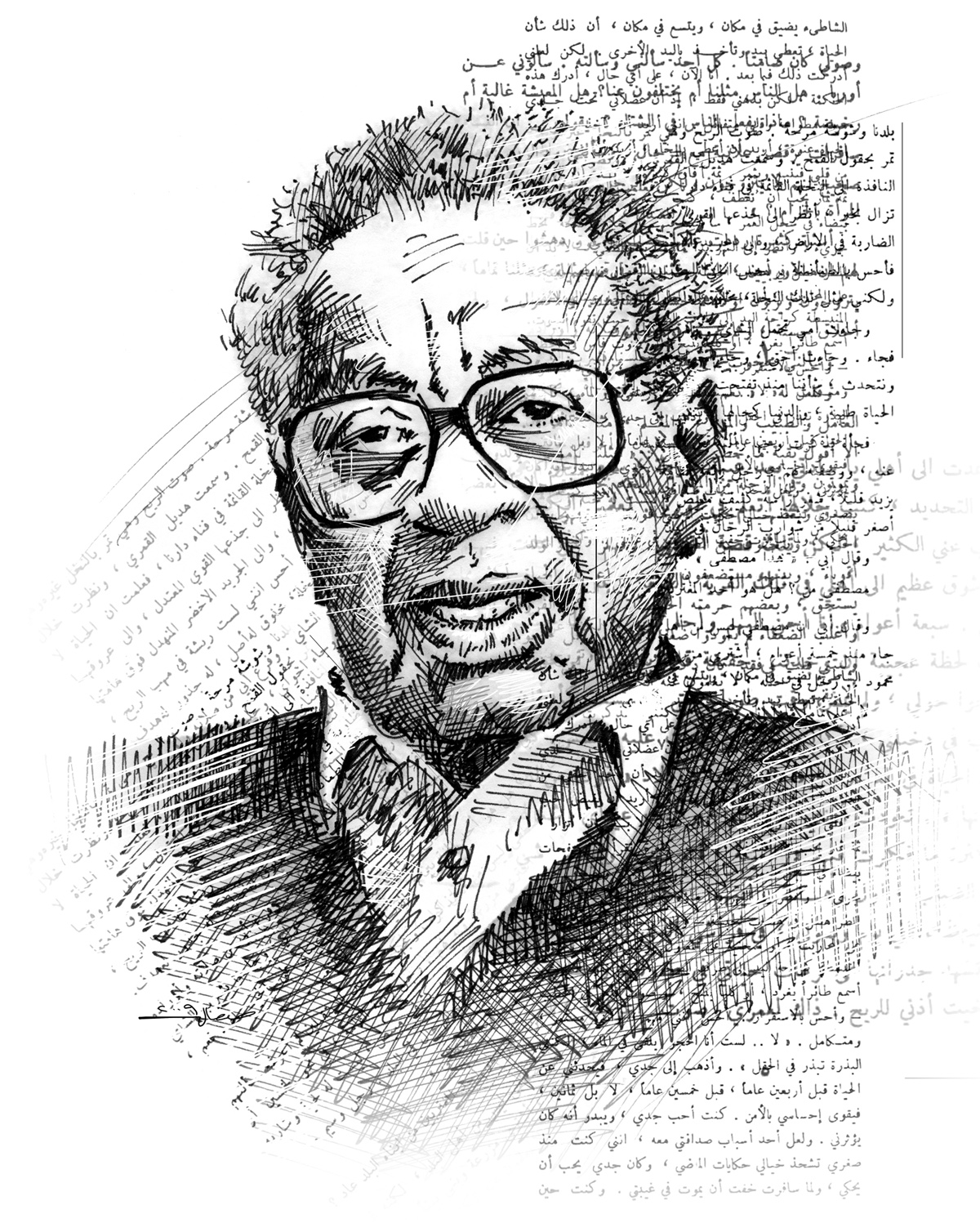

Tayeb Salih by Mamoun Sakkkal for Al Jadid.

While some immediately think of the violent crisis in Darfur at the mention of Sudan, others will remember Tayeb Salih, the legendary Sudanese writer who passed away in London at the age of 80. His monumental novel, “Season of Migration to the North,” first published in English in 1969, is considered by many critics to be the work that launched contemporary Arab literature onto the world stage and into the modern canon.

Born in a northern Sudanese village in 1928, he studied at Khartoum University. Four years before Sudan’s independence in1956, Salih left for England to study international affairs at the University of London and to work for the BBC drama department. Later he worked at Qatar’s Ministry of Information and for the UNESCO office in Paris. More recently, he wrote for the London-based Arabic magazine Al Majalla.

A benevolent supporter of Arab literature, he lamented the lack of translations of Arab writers to English and observed that “When there is a political crisis, people jump to the wrong conclusions because they have no terms of reference,” he told Al Jazeera. A champion of human rights, he was a vocal opponent to the previous Islamic regime in Sudan and the political misappropriation of the Koran. An émigré like the Irish James Joyce, Salih’s fiction continually looked home towards the Sudanese village for his inspiration. Like the English Thomas Hardy and the American Nobel-prize winning novelistWilliam Faulkner, Tayeb Salih’s universal and human dramas are set in the imaginary and unpretentious village, Wad Hamid.

In his first collection of short stories in 1960, the story “Doum Tree of Wad Hamid,” a dramatic monologue, began Salih’s literary exploration of the outsider and modernity intruding on village life. His characters also had to wrestle with the indigenous oppression and corruption rooted in either the village or within the family. In the story “A Handful of Dates,” a young boy perceives the cunning ruthlessness in his beloved grandfather. The grandfather figure, as carrier of culture who passes on both the diseases and beauty of the Sudanese village and burdens the grandson with responsibility, is a constant motif for Salih. In his “Tayeb Salih, Ideology and the Craft of Fiction,” the Arab-American critic Wail Hassan writes “In the Wad Hamid Cycle,” the recurrent theme of the grandfather-grandson relationship often frames concerns about the old and the new, tradition and modernity, conformity and dissent.”

The famous novella published in 1967, “The Wedding of Zein,” typifies Salih’s dexterous mingling of both Sudanese oral culture and the classic Western canon. As a character reminiscent of Shakespeare’s wise fools, Zein, the androgynous animal-like fool, is also endowed with spiritual sensibility and an appreciative eye for beauty. When he returns from a hospital visit, now more handsome than grotesque, he marries his lovely and willful cousin and stands “like a mast of a ship.” Later, “Wedding of Zein” was dramatized in Libya and made into a Cannes Festival prize-winning film by the Kuwaiti filmmaker Khalid Siddiq.

A second contiguous novel of politics in the village, “Bandashar,” also published in 1967, delves into Salih’s staple themes of myth formation, the seduction of surrender, the life force of the Nile and a maternal love slightly tinged with adolescent sexuality. In the depiction of village life, Salih’s narratives remain rooted to his landscape in the diverse social groups, the corruption, problems of irrigation, the celebration and the unhealthy restraint of tradition. Salih turned to these universal and symbolic motifs once again in his seminal novel, “Season of Migration to the North.”

A few years after its publication in Beirut, the translated “Season” had an auspicious publication in the literary magazine, Encounter. Later the publication was found to be financed by the CIA through the “Conference for Cultural Freedom.” Although “Season” has become a Penguin Classic, a rarity for a contemporary Arab literary work, its explicit sexuality and frank discussion of Islam, even touching on female circumcision, caused it to be banned in Egypt and today it is still banned in the Sudan and the Gulf.

In a now familiar scene that juxtaposes Eastern and Western culture, the novel opens with the return of a poetry student who discovers a stranger ensconced in the village. When the student hears the stranger, Mustafa, drunkenly recite a poem by Ford Maddox Ford, the student is drawn into the violent past of Mustafa’s sojourn to England. Critics have compared the sophisticated novel to Joseph Conrad for its condemnation of colonialism and double-frame narrative which blurs the boundaries between the narrator and the tale. For critic Issa Boullata, Salih’s novel “emphasizes the political side of the East/West confrontation as internalized by Mustafa Said and perverted into a vengeful feeling expressed in sexual conquests…” The author himself pointed out , “I have re-defined the so-called East/West relationship as essentially one of conflict, while it had been previously treated in romantic terms.” While in London, the character Mustafa identifies himself to his female conquests as “African-Arab,” highlighting the political complications that move beyond the East/West paradigm and foreshadowing the tensions in the Sudan.

Yet the crux of the novel rests in Salih’s response to the Great Bard illustrating the depth and longevity of cultural preconceptions. During his trial for murder, while the lawyers duel for the winning narrative, the novel’s protagonist thinks to himself, wants to lash out, “I am no Othello. I am a lie.” Still he remains silent. Almost 50 years later, when the literary device of a response to a traditional canon narrative has become mainstream, “Season” retains the power to shock readers out of their complacency. With the literary references to both Arab and British cultures, the narrative displays an intellectual depth and awareness of performance as a political posture as “sharp” as Mustafa’s innate intelligence. David Pryce-Jones’ review for the New York Times aptly praised the translation: “Swift and astonishing in its prose, this novel is more instructive than any number of academic books.” Celebrated critic Roger Allen describes the novel’s construction as “brilliant” as the narrative crosses cultural boundaries. Allen writes that “A major device that the author uses to convey these misunderstandings at the broadest cultural level is that of place, and, specifically, two rooms.” The double place is mirrored in the two dead wives, Jean Morris in England and Husnah Bint Mahmudin in Wad Hamid. In “The Experimental Arab Novel,” critic Stefan Meyer writes, “The book is significant in many respects, but perhaps in no greater respect than the way in which it explores the intertwined relations between gender and power relations.”

Within the umbrella of East/West, the novel weaves a plethora of dialectics: male/female, Christian/Muslim, Eros/Thantos, North/South, Tradition/Modernity, Urban/Rural – enough to keep generations of academics writing about the undiscovered nuances in the novel. Critics have yet to agree on the novel’s final image. Issa Boullata reads the ending as an affirmation of life when the narrator “chooses and makes a decision for the first time in his life,” while others debate the futility of the narrator’s final cry. Salih’s legacy will continue to inspire Arab intellectuals and Western humanists.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 60, 2009.

Copyright © 2009 AL JADID MAGAZINE