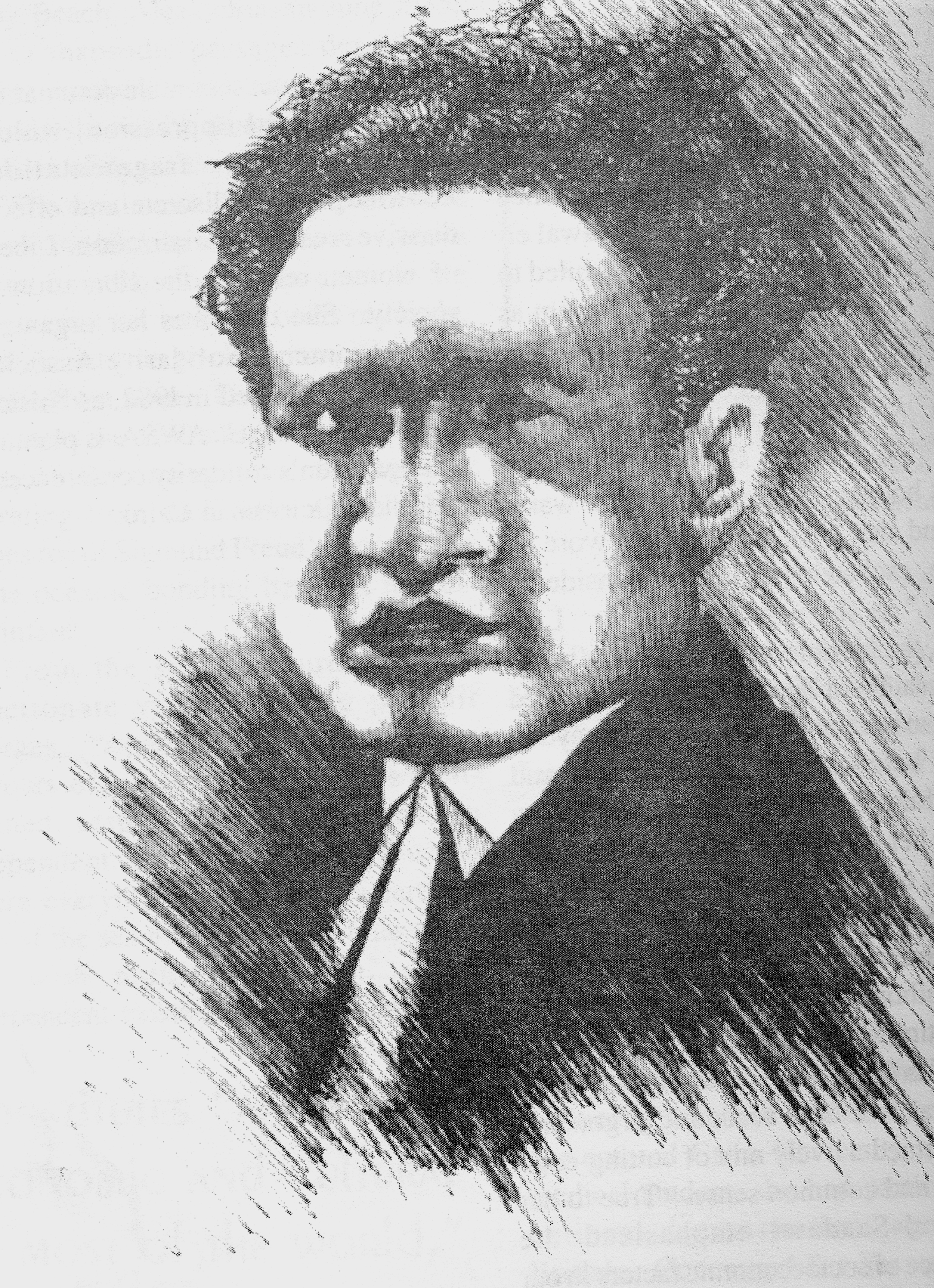

Sayyed Darwish by John Sayre for Al Jadid.

This article was adapted from a chapter on the music of Sayyed Darwish in "Fi al-Musica al-Lubnaniyya al-Arabiyya wa al-Masrah al-Ghina'i al-Rahbani" (About Lebanese Arab Music and the Rahbani Theater Musicals), by the late Nezar Mrouhe, edited by Mohammad Dakroub (Beirut: Dar al-Farabi, 1998). This article is edited and translated from Arabic for Al Jadid by Sami Asmar.

Sayyed Darwish remains unknown, as does his message among the musicians who came after him and those who have wandered from the tradition he established. However, Sayyed will not remain in the abyss of obscurity as long as millions are attracted to "modern music." As they search for modern music, they will realize that there is a void and that the development of new trends in Arab music is necessary. No one has stepped into Sayyed's empty place.

Born in Alexandria in 1892 and died in 1923, the musical legacy of Sayyed merits attention for many reasons, foremost of which is his school and his method. Darwish's career highlighted his modernist attempts in counterpoint composing and his establishment of an operatic landmark. These achievements permeated all his musical traditions.

The goal then is to show the role folk art and the music of Darwish's times played as the origins of this pure art and as an influence on Sayyed Darwish's work. The two best methods for unearthing his musical roots are through an in-depth study of the characteristics of Darwish's art and by rescuing his art from oblivion and liberating his legacy from oppression by presenting his works and plays to large audiences.

Many attempts have been made to suppress Darwish's musical legacy, for reviving his contributions will expose how much some musicians have "borrowed" from him. Thus, bringing the musical legacy of Sayyed into the public domain is a step toward revitalizing Arab music and setting the record straight.

Folk Art

Egyptian folk art constitutes the primary source of Sayyed Darwish's works, and therein lies his genius.

What is folk art? It is the aesthetic representation of a people's feelings and notions of life, in which form and content assume an indigenous nationalistic feature. It is the truthful, sincere, and deep expression of the peculiar features of a certain environment. Folk art collects stories, legends, proverbs, folk tunes, songs, and instruments accumulated by people over time. History contributes to the definition as well, for folk art not only incorporates the people's views of life, women, love, and other matters, but it is part of that group's history, recounting political and economic crises and at times serving as a valve for the release of political pressure, especially if people live under a dictatorship or colonial occupation. In folk art, one finds the glorification of nature, motherhood, the family, and freedom.

Reviving folk art serves several goals: first, revealing an endless beauty; next, achieving artistic and intellectual pleasures through the study of honest and warm human production; third, fulfilling a national mission by facilitating a people's understanding of its truth, discovering its noble traits and how they are consistent with its national wishes; and finally, strengthening its self-confidence and encouraging the leadership to value happiness and culture in the nation.

Egyptian Political and Musical Scene

Life in Egypt during Sayyed's childhood and maturity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was rife with tumultuous events, unrest, and oppression stemming from British colonial rule, which marked the country's day-to-day political life. Fundamental changes in the structure of Egyptian society since the reign of Khedive Ismail — affecting politics, social life, economics, and culture — produced a middle class and the nascence of a working class. This young, new class began struggling against feudalism, the Khedive, and British imperialism and its supporters in Egypt.

These developments culminated in the Urabi nationalist revolution, which ultimately failed. However, the ideas of Urabi and his revolution survived in the conscience of the Egyptian people, paving the way for the emergence of Mustafa Kamel in 1890; he assumed the leadership of the Egyptian national movement from Urabi after the British bombardment of Alexandria. Sayyed Darwish spent his childhood and youth in this inflammatory atmosphere filled with talk of nationalism, revolution, freedom, and fierce opposition to the British.

The literature and arts of that period reflected the decadent social conditions. The prose was mainly rhymed and embellished statements arranged according to a pattern later deemed inferior. The same can be said about poetry and theater, which largely glorified feudalism and the rulers and defamed the Urabi revolution. Music was embedded with Turkish, foreign, or Eastern tunes alien to the popular Egyptian singing traditions. The music was loose: merely embellished rhythms, a form of tarab that lacked any expressionistic value.

Following WWI, thousands of Egyptians suffered at the hands of the British occupation. Ordinary Egyptians were thrown into labor camps, nationalist activists sent to prison, and others into exile. In an atmosphere fraught with resentment against the colonizer, Egyptian singers showed little sympathy for the ordeal of their people, nor did they appear affected by the war that had set the world ablaze. They continued their heedless drinking of alcohol and shameless use of drugs, while singing was only an amusement to kill time. Sayyed, however, was not like these other musicians.

The revolution of 1919 broke out as a result of increased political awareness, the development of new ideas, and the availability of cultural activities, mainly by collaboration among artists, writers, journalists and the nationalist leaders to foster patriotic feeling in the people. Sayyed contributed chants and songs that were used to incite enthusiasm in the tumultuous demonstrations; especially effective was his call for national unity and for abandoning differences for the sake of fighting the colonizer. One of his lyrics which the crowds chanted stressed the unity among Muslims, Christians and Jews, claiming that those unified by a nation cannot be separated by religions.

The salient feature of singing at the time, which unfortunately remains characteristic of modern Arabic singing, was the absolute sanctification of the human voice. Singing was no more than manipulating the voice and fine-tuning the vocal cords in repetitive and similar tunes, at the expense of artistic expression. The lyrics lost meaning and the music lost its aesthetic ability of comprehensive expression. Anybody who had a good voice and memorized the known tunes was considered a singer. Most tunes were Turkish or of non-Arab origin, and thus alien to Egyptian popular musical traditions. One realizes the crisis which plagued Egyptian musical and singing art.

Abdo al-Hamouli and Mohamad Uthman tried to bring change and variety to the tunes but were unable to break to the circle of tatreeb (reaching the state of ecstasy or tarab through repetition of the musical motifs), because they did not fully realize that the goal of art is expression. The same criticism can be leveled at Salama Hijazi, despite the fact that he broke into the realm of operatic composition.

Childhood and Youth

Sayyed was raised in one of the poorest suburbs of Alexandria, Kom al-Dukka, by his father who worked as a carpenter. He prepared from an early age to become a sheikh, a religious official. With the sudden death of his father, the loss of the family's main supporter, Sayyed went to work to support his mother and sister. He began as a cantor in religious ceremonies, and then moved to singing in clubs with an ensemble under difficult and undignified conditions. The low pay forced him to mingle with customers, to drink alcohol, and to visit brothels; this lifestyle eventually led to alcohol and drug addiction. During this period, however, he learned to compose music, with his early compositions reflecting his feelings and lifestyle at the time.

As he developed, however, his music was characterized by seriousness, energy, and strong features of Egyptian society. His compositions quickly became very popular. He composed his best-known musical roles at the time, along with Andalusian chants. His dawr (a song type) in "Fi Shari'h Min" (In Whose Laws) is considered a breakthrough in Eastern music since it is composed according to a maqam (tonal mode) invented by Sayyed himself and called "Maqam Zanjaran."

He was an artist of conscience, unwilling to produce the type of art that was then prevalent. He believed that his art was holy and should be made available to the millions rather than for the entertainment of a few individuals. Sayyed Darwish's contributions transformed Eastern music from one world to another, where it ceased to be mere amusement or entertainment.

The Art of Sayyed Darwish

The origins of Sayyed Darwish's art are rooted in the pure Egyptian spirit and popular Egyptian artistic traditions. His love of Arab arts expresses itself in one of Sayyed's plays, "Abdul Rahman Nasser." Sayyed's works relive not only the distinguished character of Egypt's different social classes, popular tunes, and literature but also his personality: he was pure, simple, and truthful to himself and others about his feelings. His tunes were consonant, and his lyrics were simple. His music was expressionist and creative, unmatched to this day. He earned his distinction by singing not for the rulers and the feudal lords but the people. He turned his back on the past to live a renaissance, a revolution in the present and the future, which covered music, arts, literature, and all aspects of life.

One appreciates the value of what Sayyed Darwish brought into music only after realizing the difficult conditions of the time. His attempts at renewing the popular focus of the art were the beginning of a chain comprised of Taha Hussein, Haikal, al-Mazeni, Mukhtar, and others.

His music was a revolution against all the uncreative and untruthful art of the time. Even his love songs reflected how people truly viewed love, desire, and sex. His singing was a departure from that presented by singers of the time, who were known for their distasteful lyrics and for cheap, open flirtation.

Zakaria al-Hijawi correctly noted the importance of one aspect in Darwish's art in an article in the magazine Al-Rissala al-Jadidah, pointing out that the so-called Eastern tunes were generally alien to Arab and Egyptian music. Darwish was accused of not knowing the true Eastern methods, while he was laying down the basis of local Egyptian popular art. He drew his art from his Egyptian environment, ignoring the inauthentic Khidevate art.

Because he threatened the establishment that both the people and their artists rejected, the establishment fought Sayyed Darwish in his lifetime and continues to fight him in our time. The people did not appreciate much of what was called modern music.

Sayyed Darwish is a master of musical expression not only of his personal emotions and his heritage, but also of the poor Egyptian classes, hard working people with rich values. They fought colonialism and the ruling classes by singing songs that expressed their true feelings and liberated their deepest sense of oppression. In his music, Darwish also represented the image of the very poor, like water-sellers, porters, cobblers, waiters, shopkeepers and lottery vendors. No one has done this since Sayyed. Those who tried failed; their attempts amounted to insulting the dignity of the poor classes.

Musical Plays

When Sayyed left Alexandria for Cairo in 1917, he was 25 years old. Although young, Sayyed had accumulated an impressive resume of artistic experiments as well as an acclaimed reputation, experience that prepared him to establish a singing-musical theater, a shrine for a great new art. Stage acting was not new but fell short of meeting high artistic standards. It consisted of light singing, comedy, and shallow topics that were removed from the concerns of Egyptian society.

His first composition was "Fairuz Shah" for the George Abyyad Troupe, a work which made significant contributions to the musical theater. Sayyed followed this with many compositions for several Egyptian groups, including Naguib el-Rihani, Ali al-Kassar, Munira al-Mahdiyya, and Awlad Akasha. He composed for his own troupe the tales of "Shahrazad'' and "Al-Barouka."

Sayyed Darwish never reproduced the same tunes despite his prolificacy. His compositions did not necessarily need great voices to be performed, as if he wanted to challenge those with beautiful but limited voice capabilities. That is how the likes of Aziz Eid, Mahmoud Reda and Estephan Rosty were able to sing and give their audiences strong feelings and plenty of laughter. The audience laughed even when the scene or acting was not meant to be comedic because of the way the music made them feel. Thus, his music for theater was different from the music prevalent at the time.

His plays were full of situations that depicted the different faces of society, often playing with stereotypical characters. Hussein Fawzi wrote after watching one act of a Darwish play, "I had the opportunity to attend a commemoration of Sayyed Darwish and listen to a piece on a particular subject. The scene was of a bunch of public writers (scribes) on the side of the road and a number of peasants who had hired them to write letters to public officials. I have listened to world music for 30 years and am not easily moved, but I assure you that I had to hold my tears at this sad yet funny scene. It was musically moving to the utmost level. I was suddenly sad that Sayyed Darwish died young, but I am happy that he is alive through his music. His music is worthy of living."

Mohamad Mahmoud notes in his book, "The Story of Sayyed Darwish," the story of the birth of one of Darwish's compositions. The story reflects Sayyed's fidelity to the art and the honesty of expression. When Sayyed read the script of Rihani's play "Wa Laww," he took note of the words of the song of the water-sellers but could not come up with the appropriate melody, and almost turned down the work because of it. He then noted that the tune was to be performed by a group of water-sellers complaining about the water company competing with them and ruining their ability to make a living. Their song started with the traditional call of street water vendors, namely, "Allah will compensate, Allah will make it easier." Hence, he concluded that he must hear the real water-sellers before he composed the music. The next morning, as we sat at a coffee shop in the neighborhood of water sellers, it was not long until one of them called the traditional call. Sayyed repeated the call after him, and then the tune naturally flowed out of that inspired yet realistic situation."

Many of his melodies were adopted from the calls of vendors and the characters that are heard and seen daily on the streets. After Darwish recreated the calls in an artistic way, the people felt that they were hearing their own voices. In the same correct artistic manner, Darwish composed melodies expressing the Arab spirit. This was clearly illustrated, for example, in the play "Abdul Rahman Nasser." He also wrote Sudanese and Greek tunes, full of Sudanese or Greek spirit. In reality, it was great new theme music and a shrine for creative Egyptian music.

There were unique innovations by Sayyed that were invaluable and reflected his genius, most prominently his composition of two different melodies that were sung at the same time. He never knocked on the same doors but explored new methods. He felt that the listener would not appreciate the beauty unless the ear combined two different elements in one framework. He did this without studying this complex subject in Western music. At the end of the opera "Shahrazad," the hero was facing enemies at one corner of the stage as they told him "You would never be any good," and his followers on another side singing "You will be victorious," at the same time in two different, but united, melodies. Hussein Fawzi called this a true counterpoint composition.

Translated from the Arabic by Sami Asmar

This essay appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 29, Fall 1999.

Copyright © 2024 AL JADID MAGAZINE