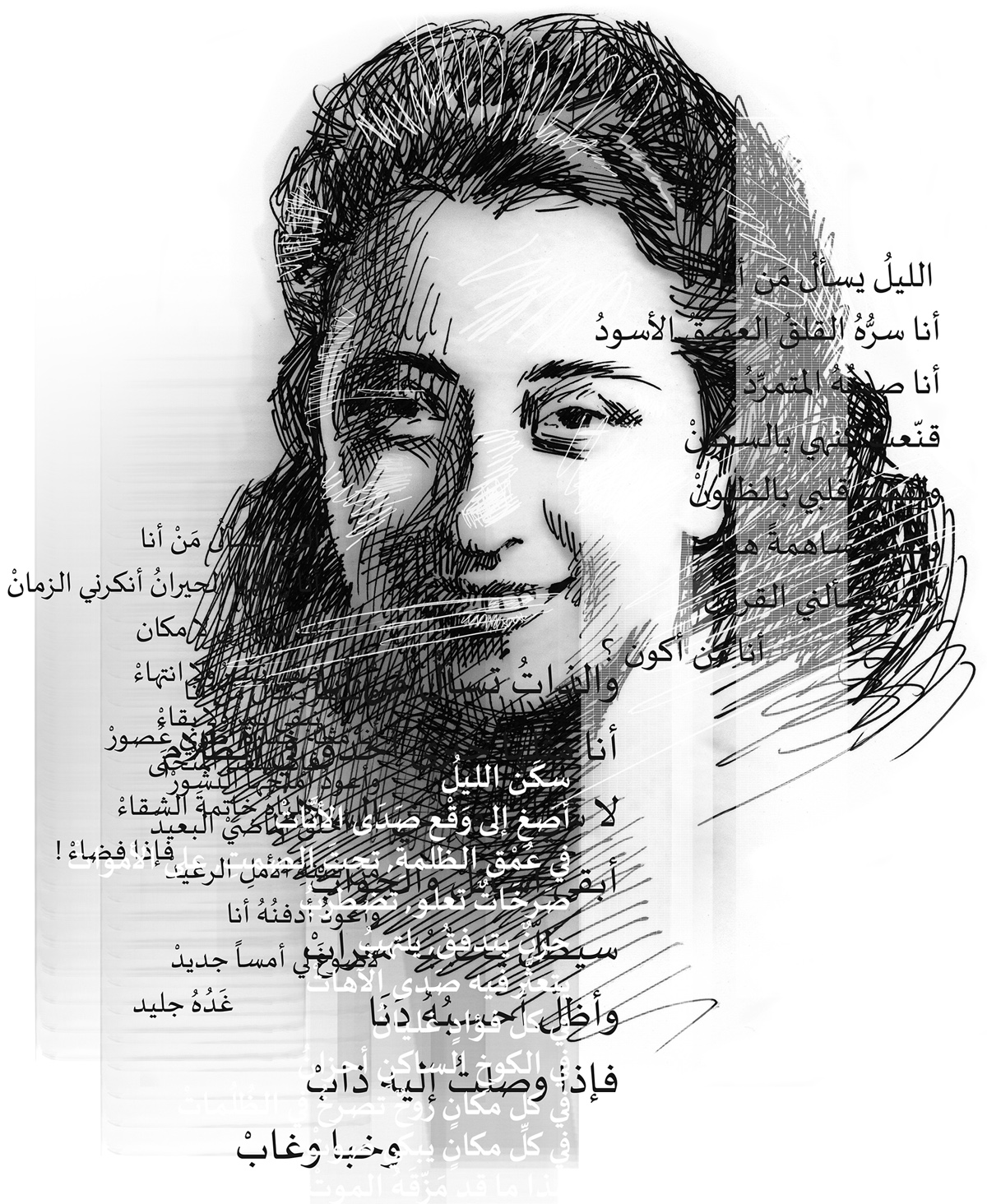

Nazik al-Malaika by Mamoun Sakkal for Al Jadid.

Nazik al-Malaika, one of Iraq’s most famous poets, died June 20, 2007, at the age of 83. Al-Malaika was best known for her role as a pioneer of the free verse movement, making a sharp departure from the classical rhyme form that had dominated Arabic poetry for centuries.

Al-Malaika was an anomaly in her society, and her legacy as a poet resulted from her breaking away from many traditions. The leap from classical poetry to free verse was very controversial, and she faced intense criticism from not only traditionalists, but also her own family. She was highly educated, fluent in four languages, and gave impassioned speeches on women’s role in Arab society – urging them to have more of a voice and challenging the deeply entrenched patriarchal system. She achieved financial independence, which was highly unusual at that time. In her writings and speeches she shared intensely personal revelations, yet preferred to remain physically secluded from the outside world.

Nazik al-Malaika was born in Baghdad on August 23, 1923, the oldest of four children. She was named after Nazik Alabed, a hero who had led a series of revolutions against the French occupying army in Syria in 1923. Her father, a poet and language instructor, encouraged her to read. Her mother, also a poet, had published her own work under the pseudonym Oum Nizar al-Malaika, a common practice at that time for women authors, and a tradition that her daughter would later change. Nazik al-Malaika graduated from Baghdad University in 1944 and later completed her masters in comparative literature at the University of Wisconsin.

With both of her parents as poets, it is no surprise that she wrote her first poem at the age of 10. She later co-wrote a poem with her mother and uncle titled “Between My Soul and the World.” Al-Malaika’s first collection of poems, “Night’s Lover,” was published in 1947. These poems were written in classical form, and were influenced by her love of traditional music and the beauty of her home. Al-Malaika had studied the oud under esteemed musical composers and would often play alone in her garden for hours. “Night’s Lover” seems to revel in quiet reflection and a private relationship to the natural world, a departure from Arab poetry’s more common theme of passion and unbridled ardor. According to Dani Ghali in An Nahar newspaper, critics at the time did not approve of al-Malaika’s difference in tone, saying she lacked her male contemporaries’ emotional electricity.

That same year, al-Malaika published her groundbreaking poem, “Cholera.” Inspired by the devastating radio announcements of the disease’s rising death toll in Egypt, al-Malaika put pen to paper. In her autobiography, excerpts of which were published in the electronic newspaper Elaph, she writes of the poem’s creation: “Within one hour I had finished the poem and ran down to my sister Ihssan’s house. I told her I had written a poem that was very strange in form and that it would cause controversy. As soon as Ihssan read the poem she became very supportive. But my mother received it coldly and asked me, ‘What kind of rhyme is this? It lacks musicality.’” Al-Malaika’s father was also critical; she says he mocked her efforts and predicted its failure, yet she stood by it, stating simply, “Say whatever you wish to say. I am confident that my poem will change the map of Arab poetry.”

Both of al-Malaika’s predictions were correct. Although modern free verse would ultimately become very popular, in large part because of her poem, it wasn’t readily accepted at first. Al-Malaika grew up in a literary world that was tied to the old ways and viewed experimentation as the antithesis of tradition, an unwanted guest. Conservatism was hard to break away from and the beginning of free verse was fraught with understandable trepidation, according to Abd Alqadar Aljanabi, in Elaph. Al-Malaika was faced with a double edged sword – though the intellectual environment opened doors to innovation, the conservative character of society suppressed tendencies toward modernism.

In addition, there is an ongoing debate over whether “Cholera” was really the first Arabic poem to be written in free verse, and thus whether al-Malaika was its creator. Some say the poem was the result of a movement al-Malaika was at the forefront of, but maintain that she was not its sole leader. According to media accounts, there was a battle between Badr Shakir al-Sayyab and al-Malaika. His first free verse poem, “Was There a Love?” (from his collection “When the Flowers Decay”) was published on November 29, 1946, a year before “Cholera.” Later on, al-Malaika herself acknowledged several poetic attempts done in free verse circa 1932 by Ali Ahmad Bakatheer. And in her influential 1962 book, “Issues of Contemporary Poetry,” al-Malaika writes about Mahmoud Matloub, who published a poem called “Free Composition” in 1921.

The debate over the first innovator of free verse is one that remains to this day. However, at the time she perceived the challenge to her accomplishment as an insult, and it ignited in al-Malaika a desire to retreat from public literary life. According to Salah Hassan in An Nahar newspaper, “She closed the door behind her forever after the whole world ignored her and failed to acknowledge her as the true pioneer she was.”

Ironically, 20 years later, al-Malaika “launched a counter- revolution against free verse in 1967, claiming everyone would turn back to the classical form,” according to Saadia Mufrah in Al Hayat newspaper. In doing so, she both disappointed and ostracized herself from certain peers and literary bodies. According to Fakhri Saleh in Al Mustaqbal newspaper, al-Malaika never intended for modernism to go as far as it did, a position which garnered her reprimands from the influential modern poetry magazine Shir. Despite these changes in sentiment, most of her work remains an amalgamation of past and present, of free verse and the classical form.

Despite her change of heart, al-Malaika’s fame in the modernist movement gave her a unique opportunity: it allowed her to become a true inspiration for women. She was an independent thinker, a respected scholar and a prolific writer who expressed herself eloquently. She managed to excel in a world that was male-dominated, and it was especially significant that she excelled in the literary arena. What women experienced in Arab society at the time was the impulse to suppress, not express, their emotions and inner life. In a way, she became a voice for those who felt unable, or not allowed, to use their own voice. Shawqi Bzai wrote in Al Mustaqbal newspaper, “She contributed significantly to Arab women proving they have a role in language. She came to feminize modernism, breaking the barriers between male and female writers, and she paved the way for future poets.”

In 1953, al-Malaika delivered a lecture in the Women’s Union Club with the title “Women between Two Poles: Negativity and Morals,” in which she called for women to be emancipated from the stagnation and negativity found in Arab society. In her essay, “Women Between the Extremes of Passivity and Choice,” she challenged the patriarchal system of her native land and became a formidable voice capable of constructively dissecting social structure. One of her most famous poems, “To Wash Disgrace,” tackled a daring topic at the time – honor killings – and caught the attention of the international media. Al-Malaika also formed an association for women who opposed marriage, offering a safe haven to those who refused to embrace the traditional role of wife and mother. The association disbanded eventually; in the assessment of Karim Mreuh in Al Hayyat, they opted for the traditional role in the end, al-Malaika included. In 1961, she married a colleague, Abd Alhadi Mahouba.

Although al-Malaika opted for a traditional role as wife, she continued her writing about non-traditional subject matter. She began to write more and more about the Self. Her work was infused with the romance of individualism. Akl al-Awit, in An Nahar Cultural Supplement, describes her as a “pioneer through her romantic courage and individualism, which elevated the self over the tribal, religious, collective.” However, it wasn’t just the Self that she celebrated in its liberation from cultural or spiritual confines.

The makeup of al-Malaika’s mind has been a major topic of discussion in the literary world. The poet was highly self-aware of her personal psychology, and did not shy away from attempting to explore all of its dark recesses. Arab women rarely made such an attempt at the time. She wrote of her well-known struggle with depression in her autobiography: “In my memoir, I delved into deep psychological analysis. I discovered I was not expressing my own ideas and emotions like other people around me were doing. I used to withdraw and be shy. I made the decision to move away from this negative way of living. My memoir witnessed this great struggle with myself in the hope of accomplishing this goal. Whenever I made one step forward, I took ten steps backward, which meant a complete change took me many long years. Today I realize that changing psychological habits are the most difficult.”

Some sources say she suffered from a depression so deep she eventually would no longer even see family members, much less a stranger. Her husband, and later her son, protected her and acted as a barrier to the outside world. According to a longtime friend, Hyat Sharara, as cited by Karim Mreuh, sadness did not just suddenly appear as an adult, but had been her companion since childhood. In her autobiography, al-Malaika attributes the origin of her melancholy to the death of her mother, who had been a close friend and fellow poet throughout her life. After the 1953 death of her mother, al-Malaika recalls that she cried night and day, until sadness became an illness that overtook her.

It is hard to imagine such an unconventional woman retreating from the world she challenged and understood so well. She had left Iraq for Kuwait in 1970, two years after Saddam Hussein came to power, and left Kuwait for Cairo after the invasion in 1990. As the years passed, she became more and more solitary. Perhaps as a defense mechanism against speculations of her surrender to depression, Samer Abu Hawash, in Al Mustaqbal newspaper, observed that al-Malaika romanticized isolation as something to be cherished, and that she felt she had lost many years while attempting to be social. But according to Khayri Mansour in the London-based Al Quds Al Arabi, “Her isolation had a tragic impact on the amount of work she produced. If illness and exile had not befallen her, we would have a lot more to remember her by.”

Nevertheless, al-Malaika leaves behind some of Iraq’s most cherished poetry, including such collections as “Night’s Lover” (1947), “Sparks and Ashes” (1949), “Bottom of the Wave” (1957), “For Prayer and Revolution” (1973) and “When the Sea Changes Colors” (1974). Short stories include “Jasmine” and “The Sun Beyond the Mountain Top.” In 1970 she wrote a long poem titled “The Tragedy of Life and a Song for Man,” building on her 1952 “Lament of a Worthless Woman.” Her last poem, “I Am Alone,” was written as a eulogy to her husband. Her role as one of the innovators of free verse changed the face of Arabic poetry, and her outspoken comments on traditional, and particularly male-dominated, society have secured her a genuine legacy as a pioneering woman.

Al Jadid editors contributed research, translation and editing to this article.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 13/14, Nos. 58/59, 2007/2008.

Copyright © 2008 AL JADID MAGAZINE