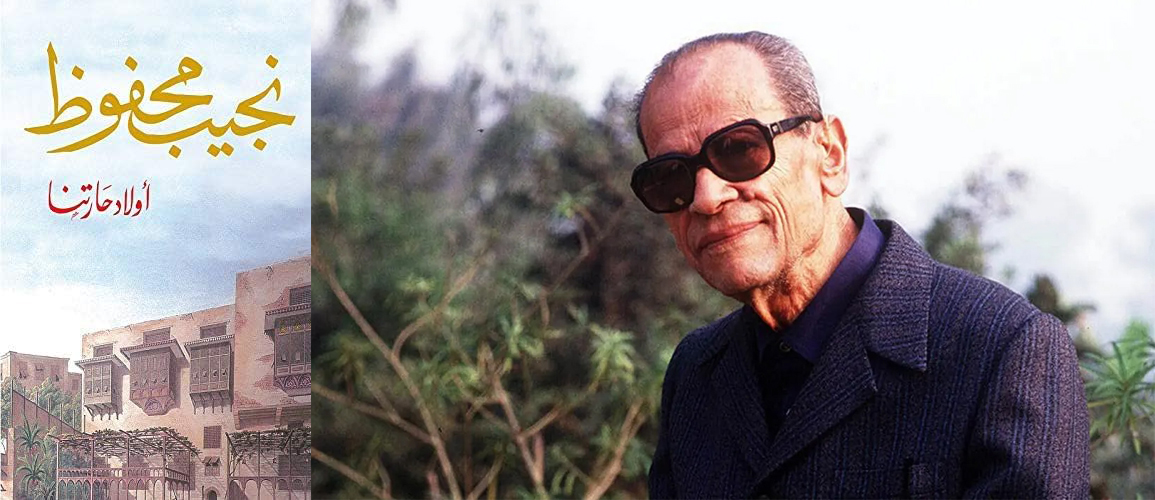

On the left, Naguib Mahfouz’s “Awlat Haritna” (1960). On the right, Naguib Mahfouz, pictured in 1989, photograph credit Sipa Press/Rex.

Since before “The Trilogy,” that is, since “New Cairo” (1945), “Khan al-Khalili” (1946), “Ziqaq al-Midaqq” (Midaq Alley, 1947), and others, Naguib Mahfouz has been the most influential fiction author that I have read. I was astonished by the questions he raised, the possibilities he presented in his characters, and the profound events they lived through. I was also amazed at the changes in his characters’ worlds throughout the different periods of his novelistic journey.

“The Trilogy” and the preceding novels constitute what some have labeled his “Realist Period” (1945-1957). They can be classified together in terms of place, style, type of characters, and use of language. The issues of revolution and social change make up the deep currents of this period in Mahfouz’s novels, in which avant-garde personalities and political activists were looking toward a new future.

Was the revolution in 1952 the future that Mahfouz was waiting for? A long silence between the completion of “The Trilogy” in 1952 and its publication in 1956 answered that question. Mahfouz abstained from writing. Did “The Trilogy” — “Bayn al-Kasrayyin” (Palace Walk), “Kasr al-Shaouk” (Palace of Desire), and “Al-Sukariyya” (Sugar Street) — so exhaust his creative capacities that he needed to recharge his batteries? Or were the ambiguities in the aftermath of the revolution the most crucial factor behind his silence?

After years of strange — yet somehow not strange — silence, “Awlad Haritna” (The Children of Geblawi) appeared in 1960 and, with its questions and problems, made a substantial impact on its metaphysical world. Then, “Al-Liss wa al-Kilaab” (The Thief and the Dogs), published in 1961 — its taut style and gripping events all expressed through sharp criticism — was followed by “As Saman wa al-Kharif” (Autumn Quail, 1962), which distinguished itself by eulogizing the sad end of ancient liberalism and its vague dream of something new, remote and outside the norm. The strange and worried “Al-Shahad” (The Beggar), published in 1965, with its tenuous philosophical vision, is astonishing.

The novels of this new period were tense, terse, substantive, yet brief, and filled with clashing characters in hostile environments amid the murmur of despair and bitter cynicism. The biting criticism of “Awama Fawq al-Nil” (Raft over the Nile, 1966) and the dialogues of “Marimar” (1967), with its ideological trials, affected everyone. The profound plunge into the depths of human anxiety through essential and decisive events characterizes the works of Mahfouz.

Opinions vary over the significance of the novels of the new period due to differences in the novels’ narrative structure. Mahfouz’s stories explore the issue of freedom of expression in the wake of the 1952 July Revolution and cover that crisis by looking at different types of characters during the Trilogy period: the party characters, including the Wafdi (from the Wafd Party), Socialist, Communist, the Brotherhood, the religious and the Islamist extremists. New characters with new descriptions were introduced: the Revolution’s opportunists, its enthusiasts, police, and intelligence services.

His characters' crises, development, environment, and provocations created an explosion in Mahfouz’s narrative output. What’s noticeable here is the proliferation of novels and the variety of their atmospheres, visions, and forms.

A different philosophical approach marks the novel “Al-Shahad” (The Beggar), and Mahfouz imbued the writing with poetry and deep psychological analysis. It differs in form and environment from “Al-is wa al-Kilab” (The Thief and Dogs), in which language and tone are characterized by tension and suspense. “As Samman wa al-Kharif” (Autumn Quail) is distinguished by its condensed style, its calmness, and also by its intense internal conflict, differentiating it from the debates of the desperate, grave, and ambivalent characters in “Whispers over the Nile.”

With each new novel Mahfouz wrote, we divine new developments, changes in the mood, differences in narrative methods, and the nature of subject, form, and style. It’s as if the governing force of these novels is development and progress: in their vision, in the formulation of language, in the choice of words, in the interplay between narrative and events, and the level of tension. We could conclude that the process through which his new works were created was Mahfouz’s way of improving all areas of his craft.

I find myself drawn to the period after “The Trilogy.” The novels following “The Trilogy” were characterized by constant renewal. I tried to examine the changes in their characters and how they differed from those of the characters before “The Trilogy.” I, like others, feel that “The Trilogy” serves as a line of demarcation between two great epochs in Mahfouz’s career.

As I started to look more into the characters of the first period, I found that the “law of internal development” of the characters governs their transformations. The main characters within the novel are in constant change, development, and transformation, which takes place through conflict and interaction between internal and external forces. Although the narrative techniques vary, the storytelling methods all approximate a unified style.

This diversity, change, and unity not only expresses the development of social life but precisely the agreement between Mahfouz’s progressive view of life and people and his ability to view progress and interaction in life, people, and art.

Does the novelist remain the same throughout different creative processes? Does he stay the same while his novels and characters grow in number and character? Hence, if the novelist portrays his characters as they develop, to what extent do these characters influence Mahfouz himself? Don’t the changes and the developments in the characters carry over to the mood, vision, and style of the author himself, namely in his transformation, his development, and especially in his diversity?

The characters’ development has transformed into permanent evolution and development in the method of narration and structure inside Mahfouz’s novels during the new period. The result is that each novel differs from its predecessor in all the elements that constitute narration as if each novel by Mahfouz is a novel by a new and different author.

These changes were not spontaneous but rather had become part of Mahfouz’s artistic and intellectual consciousness. Mahfouz was developing his narrative world with its social and political causes, characters, and styles.

Mahfouz created many characters who, in turn, influenced him, continuously remaking him. The development by which these characters were governed is the same developmental process that governed Mahfouz and his artistic consciousness. As much as his novels and forms were varied, so he was varied — that is, continuously renewed and different, even into his 90s, when, in 2005, he completed his excellent book, “Dreams of the Recuperation Period.”

Translated from the Arabic by Elie Chalala.

The Arabic version of this article appeared in the Beirut-based As Safir newspaper on September 1, 2006. The author has granted the right to Al Jadid to translate and publish this article.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 12, Nos. 54/55, Winter/Spring 2006.

Copyright © 2006 AL JADID MAGAZINE