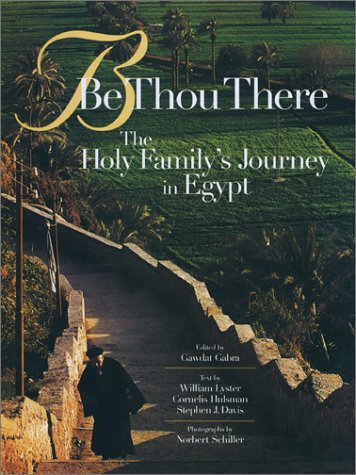

Be Thou There: The Holy Family’s Journey in Egypt

Edited and Introduced by Gawdat Gabra, William Lyster, Cornelis Hulsman, Stephen J. Davis

Photographs by Norbert Schiller

The American University of Cairo Press, 2001

According to the Gospel of Matthew, after Jesus was born, God appeared to Joseph in a dream and said to him, “Arise and take the young child and his mother and flee into Egypt, and be thou there until I bring thee word: for Herod will seek the young child to destroy him” (Matthew 2:23).

This was a defining moment in the history of the Coptic Christians, for Egypt became a second Holy Land when their own land was blessed by the presence of the Holy Family. Today, the sites where tradition teaches the Holy Family stopped, and the route they are believed to have taken forms a trail of holiness. This book is about that sacred geography.

Although the Holy Family’s stay in Egypt is central to the Coptic religious imagination, neither the length of the Holy Family’s stay in Egypt, nor the route they followed, is mentioned in the Gospels. This information first appears in the writings of second century church bishops, who spoke of the flight of the Holy Family as a fulfillment of Isaiah. Later, medieval texts with intriguing titles such as “The Vision of Theophilus” and “The Arabic Infancy Gospels” added more details, all of which were rounded out by oral traditions, apparitions, and miracles.

“Be Thou There” takes us on all of these journeys: the textual, the oral, and the miraculous. Through the lens of four scholars and one sensitive photographer, the reader travels with the Holy Family as they enter Egypt from Gaza, work their way through the Delta and along the Nile to Upper Egypt, and then return. It is a journey with many stopping points; the following merely describes two of the sites on this armchair journey.

TEL BASTA

According to tradition, the Holy Family entered Egypt by crossing the Wadi al-Arish, also known as the River of Egypt, although it is actually a small stream that forms a natural boundary with Palestine. From there, their first official stopping place was Tel Basta, or Bubastis. The names “Tel Basta” and “Bubastis” come from “Pi-Beseth” or “Per-Bastet,” meaning the domain of Bastet the cat goddess. Thus it was once a holy city, although today it is merely a field of stones with a cat cemetery.

The famous scholar of the sacred, Mircea Eliade, taught that in all cultures, sacred spaces are often marked by nature, with cooling springs, shade-giving trees, secret caves, or majestic mountains; and that these are recognized as holy through visions or signs that connect them, through religious belief, to the divine.

The mark of holiness at Tel Basta is a well over a spring that is said to have been created by the Christ child. One story of the well’s creation comes from “The Visions of Theophilus,” another comes from the local bishop, and additional information has been added by recent archaeologists.

Theophilus, an early Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria, held his office from 385 to 412 CE. Many of his sermons and letters, written in Coptic, have been preserved, albeit in 14th century translations into Arabic, Syriac, and Ethiopian. From these we learn that when the Holy Family reached Tel Basta, they were attacked by robbers. In the end, the thieves only took Jesus’ silver sandals. However, Mary was so upset that the baby Jesus made a sign of the cross on the ground, and a spring of water appeared for her comfort. According to Theophilus’ vision, Jesus then said, “Let this water help make whole and heal the souls and bodies of all those who shall drink of it – with the exception of the inhabitants of this town, of whom none shall be healed by it.” (This vengeful remark may be Theophilus’ special touch, as he was known for condemning and persecuting Christian monks who did not agree with him.)

In the 20th century, the local bishop Yaqobus had a different explanation for the well. In his rendition, the Holy Family arrived in Tel Basta and asked for food and water. Their request was refused by all the residents except one farmer who brought the family home. There, the baby Jesus healed the farmer’s paralyzed wife. The next day, the farmer took the family to a festival in honor of the cat goddess Bastet, but as soon as Mary and the Child entered the temple, the cat goddess statues fell and shattered, fulfilling the prophecy of Isaiah 19:1. Jesus then created a well in the temple, and although the town refused to convert, the well became a source of healing for all who did not reject him.

Until recently, there was no well to mark this sacred place, but in 1991, archaeologists found a well inside the temple ruins, and dated it to the first century. By 1997, they had connected it to works such as Theophilus’, at which time it was publicly associated with the Well of Jesus. Father Daniel, the parish priest in Tel Basta, believes this well is built on the top of the sacred spring of Jesus, but other archaeologists suggest that it is, in fact, only one of many first century wells in the same area.

An additional story that takes place at Tel Basta comes from “The Ethiopian Narrative of The Virgin Mary.” Although from the 18th century, it, like “The Vision,” preserves an earlier text that was originally in Coptic. In this text, at Tel Basta Jesus asked Joseph to carry him for a while because Jesus wanted to lay his hand on Joseph’s breast and thus cure him of his fatigue. It is probably because of this story that so many Egyptian icons show Joseph carrying Jesus.

MATARIYA

A sacred well and a sacred tree mark the holy stopping place at Matariya. Between the Delta and Upper Egypt, the Holy Family stopped at several places that are now inside modern Cairo. One of these is Matariya, where they are said to have found shelter under a sycamore tree, and where Jesus created a well, blessed it, and drank from it, and in which Mary later bathed.

There are many early Christian and medieval references to Matariya, including “The Arabic Synaxarium” (martyrs of the Coptic church), “The Difnar” (a collection of Coptic hymns), and “The Arabic Infancy Gospels” (one of many apocryphal Gospels relating the childhood of Jesus).

In fact, “The Arabic Infancy Gospels” say that the sacred tree emerged from a drop of Jesus’ sweat (the tradition of holy sweat is shared with stories in Islam). Local lore today suggests that this tree was a sweet smelling balsam tree, and that it emerged from the spot where Mary poured out the water she had used to bathe Jesus. This belief has been alive since at least the 13th century, when a medieval pilgrim, en route to Jerusalem, reported that he had bathed in the spring, believing it was the same water in which Mary had dipped Jesus. He also reported that he took a piece of the tree with him as a souvenir. Two hundred years later, another pilgrim suggested that perhaps this “pious pruning” had gone too far; he reported that no one was allowed to even clip a leaf from the holy tree. In any event, the tree that stands today (a sycamore fig) is said to have grown from an offshoot of a tree that grew there in 1672, and that it, in turn, was from offshoots that could be traced back to the original tree.

Matariya, like other Holy Family sites, is revered by both Christians and Muslims, as Mary and Jesus are also holy in Islam. In fact, Muslims and Christians share many ritual places and celebrations, such as the Mulid festivals that commemorate the death of local saints. Thus, Matariya, besides being designated as a site on the Coptic itinerary, has a Catholic church (St. Mary’s) and the Mosque of the Tree of Mary.

Clearly, the “Baraka,” or “blessing” that emanates from the divine to these earthly gateways is one that can be shared. In fact, Muslims, Christians, and even Jews celebrate holy places generously, forming a net of sanctity over the whole of Egypt. It is only the Copts, however, blessed by their tradition of the Holy Family, who have organized this holiness onto a road map with an itinerary, allowing pilgrims to move with purpose, expectation, and satisfaction through Egypt’s sacred landscape.

This review appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 38, Winter 2002.

Copyright © 2024 AL JADID MAGAZINE