Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran

By Saeb Eigner

Merrell, 2010

Amid so much hubbub and controversy surrounding the politics of the Middle East, one might think that the region’s visual arts are uncultivated, and the role that Middle Eastern artists play in the broader world negligible. But a new book, “Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran” by Saeb Eigner, rectifies any such misconception and brings the significant contributions of contemporary Arab and Iranian artists to the forefront.

Focused on the artists and their work, this exquisite book of images takes the reader on a journey that frames the richness of Arab and Iranian art as a continuity of styles from the ancient world to modern times. The author notes that, unlike contemporary Western art with the avant-garde movements in the late 19th century and the evolution of modern art movements after WWII, contemporary Middle Eastern art is not easily defined by key turning points. Therefore, the images displayed integrate a ubiquitous mix of the old and the new.

The point of departure is the uniquely Arabic and Iranian art forms of calligraphy and stylized scripture, the various expressions of which both amuse and astonish the reader. Where the book clearly succeeds – and what separates “Art of the Middle East” from so many others – is that, while the familiar traditional script and even the far Eastern styles with broad sweeping brush strokes are ever-present, much of the work is bold and futuristic, and presented in surprisingly unorthodox ways. In the mixed medium sculpture “The Giver of Peace” by Shezad Dawood, dry tumbleweed symbolizing the expanse of the American West is illuminated by a pink neon light that spells Al Mu’min in Arabic, one of the 99 names of God. In contrast, Iranian artist Ali Ajali’s painting “Allah” takes the reader in a completely new direction with a dense, interlocking style of Arabic script known as Gol Gasht that is at once mesmerizing and chaotic.

Politics, war and conflict naturally play a central role in the artwork featured in “Art of the Middle East.” These themes are some of the most compelling and fascinating because of the passion with which they are rendered and the emotion they evoke from the viewer. Not to be out done, the book tackles these subjects with powerful pieces that span an emotional spectrum from rage to indignation to despair. In one of the most memorable works, Algerian artist Kamel Yahiaoui laments the death of poet Taher Djaout by replacing the keys of an old typewriter with various sized bullet cartridges. In another piece, “As If Yesterday...” by Lebanese painter Oussama Baalbaki, a hovering sense of doom is clearly evident in a dying, decrepit Mercedes sedan.

It must be said that many of the images presented in “Art of the Middle East” exhibit a dark, almost foreboding tone. Perhaps it is a testament to the fact that so much conflict and strife has descended upon the region, and that the diversity and unity of the Arab nation, has been displaced by ethnic and religious factionalism which, sadly, seems to have become more important than the whole.

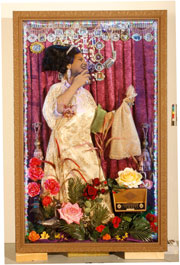

A strong sense of longing for a brighter past is present in the portraits of stars of song and the silver screen. Umm Kulthum, the cultural voice of Arab nationalism, and Omar Sharif, the most famous Arab star outside the Middle East, are immortalized in various forms, but ultimately give way to the larger-than-life political images of Nasser and Sadat. Tributes are paid to beautiful and sensuous Middle Eastern performers in portraits by Youseff Nabil and the eclectic mixed media work of Khosrow Hassanzadeh, but later dissolve into the strangely disturbing work of Ahmed Alsoudani, whose distorted faces look toward the misery of the Gulf War, and Gazan artist Laila Shawa’s bewilderment of a rifle-wielding child in “Boy Soldiers.”

In this regard, “Art of the Middle East” follows an interesting progression from light to dark. Whether done intentionally or subconsciously, the book takes on an overall more introverted, contemplative tone as the images unfold; and the high spirit of calligraphy, pattern art and personality cult morphs into the sullenness of dispossession and identity crisis. A troubled history and confused identity become metaphors for the modern Middle East, its imagery often defocused, almost aimless and abstract – a stark contrast to the crisp orderly lines and the jubilant glowing colors exhibited in the beginning of the book. To some extent one has to wonder if the psychology of conflict has really taken such a deep hold of the Middle Eastern people.

However, some of the most gripping and original images appear toward the end. Hossein Khosrojerdi’s digitally manipulated photographs of isolated figures are creepy and haunting. In “Railway” and “Man with the Rocks” mummy-like forms appear ghostlike amid magically minimalist backgrounds, reminiscent of the surrealist works of Yves Tanguy. “Paysage Pleurant” by Abdallah Benanteur also stands out as a strangely conflicted landscape that appears to question human existence. Meanwhile, “Cedar Tree” by Nabil Nahas instills a sense of rebirth into the mix, perfectly capturing the horizontal form of the cedar tree with a strangely oriental sweep of the brush.

In many ways, “Art of the Middle East” is a triumph. Thorough and complete, the book captures the emotional highs and lows of a diverse collection of artists and their work in a world where anything Arab or Iranian is too often overlooked. Without a doubt, the strength of the book is the care with which the images were chosen. Visually stunning, “Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran” is sure to leave the reader wanting more.

This review appeared in Al Jadid, Vol. 16, No. 62 (2010).

Copyright © 2010 by AL JADID MAGAZINE