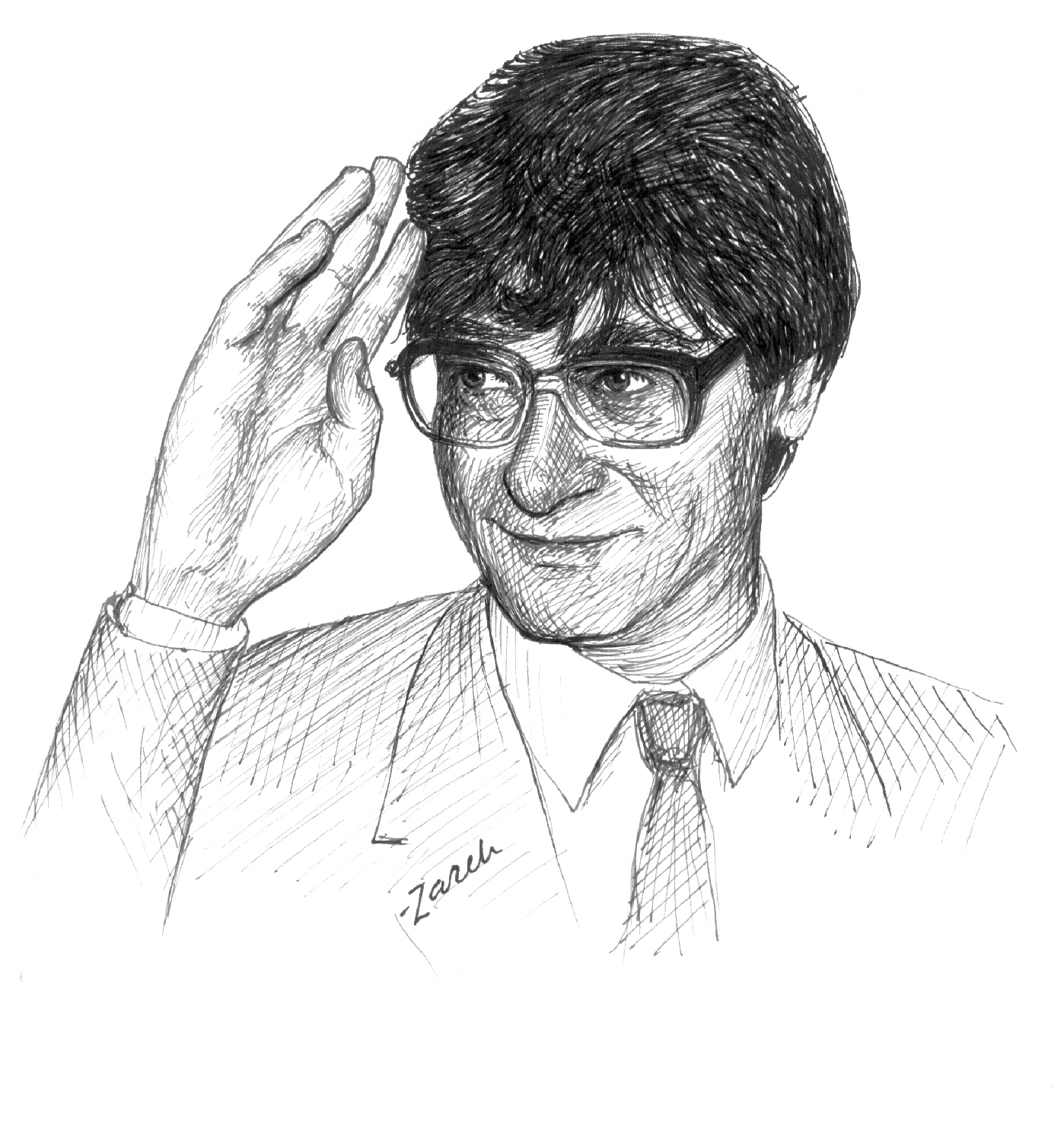

Mahmoud Darwish by Zareh for Al Jadid.

Celebrated Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish has served as a symbol of the Palestinian struggle and a model of near perfection among contemporary Arab poets for several decades. After constant harassment, including imprisonment by Israeli authorities, Darwish had to leave his homeland in 1971, moving from one country to another in the Arab world and abroad. Throughout his many moves, Darwish increased his readership and became known as a herald of “resistance poetry” or shi’r al-muqawamah. Darwish’s resistance poems can be found throughout his earlier volumes, which include “Bird Without Wings” (1961), “Lover From Palestine” (1964) and “Olive Leaves” (1964).

Darwish quickly became famous throughout the Arab world and abroad as he began and continued writing poems that allowed readers to feel with Darwish the pain of losing a home. His classic poems, which are rich in metaphor and symbolism, are favorites of the masses. Many of his poems have become immortalized and some have even been set to music by the noted Lebanese composer Marcel Khalife. Darwish is a timeless figure and, at the age of 63, is the author of more than 20 books.

Recently, several critics and scholars have noticed a change in Darwish’s poetry, straying from the political and broaching the personal and introspective. This change dates back to 1992 with the publication of “Eleven Planets.” Other volumes of poetry include “Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone?” (1995), “The Bed of the Stranger” (1999), “The Mural” (2000) and “Do Not Apologize For What You Have Done” (2004). “The Mural” has gained much acclaim and is indicative of the new elements of Darwish’s poetry. It is “intensely and painfully personal…a definite move away from the circumstantial and the quotidian to the more universal and existential issues of life and death,” according to Ferial J. Ghazoul’s review in Al Ahram weekly.

Despite his popularity, Darwish has been subject to criticism and has doled out some of his own, becoming involved in two literary battles in particular. In the first, he assailed political poetry that blatantly preached political propaganda. In a way, he himself belonged to this school of poetry since he was political; however, Darwish’s poetry always remained metaphoric, never preaching explicit incitement of the masses.

His second battle was and continues to be against modern Arab poetry. He first launched his attack in the 1980s in the Palestinian magazine Al Karmel, asking for rescue from what he considered a barrage of low-quality poetry. He renewed his criticism with a second campaign against current trends of modern Arab poetry in August 2005 at the 41st annual Carthage International Festival (July 9 – August 15). Once again Darwish finds himself in a unique role as he criticizes a poetry movement of which he is a part.

This summer, Darwish returned for the first time in five years to Tunisia on August 11 to speak about his poetry. Tunisia had been Darwish’s home after he was forced to leave Beirut along with the P.L.O. during the Israeli invasion of 1982. Recognizing Tunisia’s warm welcome, which was rare at a time when Palestinians faced many closed doors, Darwish said in opening remarks, “I am here to renew my special love for Tunis. This is the only country from which we, the Palestinians, did not leave [because we were] expelled, but rather [to return] to a part of our nation.”

These heartfelt words were met with warmth and gratitude by the more than 3,000 audience members who gathered at the Acropolium in the northern suburb of Tunisia’s capital to hear the poet speak. The director of the festival, Raouf ben Omar, returned the kind words, saying that the festival had invited Mahmoud Darwish to “restore to poetry its authority, lantern and scepter.” Tunisia also honored Darwish with the publication of a booklet titled “Mahmoud Darwish in Tunis,” in which Darwish writes glowingly of Tunisia. Also in attendance were Tunisian Minister of Culture Mohammad Aziz ben Ashour and Palestinian Ambassador to Tunisia, Mohammad Ghanam.

While Darwish showed only affection for the country hosting this festival, he offered sharp criticism of modern Arab poets. Noting an irony in modern poetry, he stated, “[this poetry] is marked by patterns despite the fact that [it] constitutes a revolution against patterns in Arab poetry.” He continued passionately, saying that poems today seem to be authorless; they blend together as little more than imitations of one another, as poets contribute nothing original in content and form.

These criticisms are notable because they were not uttered by a classicist or traditionalist, but by a modern poet. Historically, modern poetry, a movement that began in the 1950s, has been the subject of attacks by those favoring classical poetry. Darwish himself, a herald of this movement, was subject to much criticism in the past and is now one of the first prominent, modern Arab poets to criticize others within the same movement, creating a new debate within the world of Arab poetry.

Continuing with his critiques, Darwish also faulted poets for writing poems to which their readers cannot relate. There is, he asserted, dissociation between the text and the reader. Darwish added, “Poetry without a reader is nothing more than a dead text.” He blames not the poetry movement for this failure to reach its audience, but the poets themselves.

Drawing a distinction between himself and his modernist contemporaries, Darwish briefly discussed his methodology for writing his poems, emphasizing his mindfulness about his audience’s expectations and how he works to shake them. He said, “I do not accept…having my former poems act as the guarantee of the success of my subsequent poems…I prefer a creative failure to a repeated success.”

Darwish also made some controversial statements about one of the greatest Arab classical poets, Abu al-Tayeb al-Mutanabi (915-965AD) in relation to modern poetry, as reported by Pierre Abisaab in Al Hayat. Calling al-Mutanabi “the most modern of all modern poets,” Darwish ignited a debate that was intensified by what he later called a misquote by Al Hayat. Shortly after Darwish’s public statements, Abisaab’s article appeared, carrying the title “Mahmoud Darwish Opened Fire on His Contemporaries in Carthage: Al-Mutanabi is More Modern than All of You,” a mistaken representation of what was said, according to Darwish.

While we do not know whether Darwish would have written a public correction had there not been such an overwhelmingly negative reaction to his statements, we do know that Darwish waited about a week and a half before issuing his correction. In it he writes that he admired and liked al-Mutanabi’s poetry and adds that what he actually said was: “I find in [al-Mutanabi’s] poetry an excellent, skillful summary of the history of Arab poetry.”

Darwish admits that he dislikes what he considers al-Mutanabi’s blind, enthusiastic support for the state and his ambition to strengthen his poetic authority through something outside of poetry. However, despite these misgivings, he adds, “When we search for a diagnosis of our current situation, we resort to citing excerpts from the poetry of al-Mutanabi, which makes me feel that this great poet remains more lively and modern and contemporary than we are.” In this correction, it is clear that Darwish does not exclude himself from the category of modern Arab poets by saying “you”; rather, he clearly includes himself.

Regardless of this correction, Darwish’s criticism of modernist poetry is clear. Abisaab reports that Darwish’s comments were marked with bitterness, condescension and combativeness, an observation apparently not lost on other poets and critics.

Reactions to Darwish

Darwish’s words drove many poets and literary critics to respond quickly and emphatically to what some considered inflammatory remarks. Some accused Darwish of longing for the Nobel Prize in Literature, writing with this goal in mind rather than writing for poetry’s sake. Darwish denied this accusation at the press conference, saying, “Why is a poet accused of yearning for the Nobel Prize every time he attempts, through his writings, to develop his poetry and renew the effort to not repeat himself in his creative works? I do not dream of the Nobel Prize because I know that I don’t deserve it,” according to a report in Reuters by Tarek Ammara.

One poet who was disappointed with Darwish’s statements is Akl al-Awit. In an article appearing in the Beirut-based An Nahar, Awit takes issue with Darwish’s claim that modern poetry has fallen into “premature patterns,” devoid of any variety and originality. He continues that it is impossible to compare al-Mutanabi with contemporary poets, though he does agree that al-Mutanabi has modernist elements in his writings.

Taking on a sarcastic tone, Awit writes that he, too, finds al-Mutanabi preferable to some modern poets, just as he finds other modern poets preferable to al-Mutanabi. Awit concedes that there are thousands of mediocre poems written today, but warns against Darwish’s dangerous generalizations. He asserts, “There is no reason to make critical, untruthful, arbitrary generalizations, which could nullify, via their comprehensive logic, the essence of modern poetry…and its creative and enlightening possibilities.” This generalizing, he continues, is like calling an entire group of people terrorists simply because some of the group’s members have committed terrorist acts.

Awit concludes by expressing agreement with Darwish’s statements that some modern poets fall into patterns and lack creativity, but sharply criticizes the careless manner in which Darwish applied this criticism to all modern poets and poetry.

Soon after, Ahmad Bezzoun continued Awit’s argument in an article published in the Beirut-based As Safir newspaper. Though less negative in his response to Darwish’s speech at the festival, Bezzoun still offers some criticisms: “The problem with Darwish’s protest is that it falls into generalities, thus it becomes subject to different interpretations…generalization is the opposite of critical examination.”

One misinterpretation Bezzoun notes is that by some Egyptian poets, who perceived Darwish’s statements as an insult and offense to Egyptian poetry. Bezzoun then suggests that generalizations are a sign of praise or respect by the authority uttering them, calling attention to what he sees as Darwish’s quickness to label others’ poetry without inviting self-criticism.

Bezzoun also reminds readers of the cry that Darwish launched in the 1980s in Al Karmel: “Rescue us from this flood of poetry.” Originally used by supporters of classical poetry as a testimony against all modern poetry, now modern poets are using it against one another. Poets of metered verse are taking up this cry to level criticism at prose poets who viewed Darwish’s statements at Carthage as renewed criticism against them and their poetry, Bezzoun writes.

In another article appearing in As Safir, cultural editor Abbas Beydoun takes issue with what he calls Darwish’s “obvious” statements about modern poetry. Beydoun considers Darwish’s outburst nothing more than a venting of emotion. Because of this lack of an intellectual dimension, Beydoun writes, there should be no debate over Darwish’s commentary. What concerns Beydoun more than Darwish’s outcry itself are the responses to it.

Like Bezzoun, Beydoun notes inherent problems in Darwish’s generalizations and resulting interpretations. Beydoun points out that those who advocate classical poetry and dislike any form of modern poetry find vindication in Darwish’s criticisms. On the other hand, those modern poets like Egyptian Mohammad Afifi Mattar who feel the critiques were directed against them personally, are too easily offended by Darwish and have misinterpreted the Palestinian poet as having insulted Egypt. Other modern poets feel they were excluded from Darwish’s outpouring and so remain silent on the issue.

Still other poets in the Arab world greet Darwish’s words as valid criticisms that they, too, share. Majid al-Samarai, for example, sees them in a more positive light. In an essay appearing in Al Hayat, al-Samarai writes that he believes Darwish’s comments to be the remarks of a great poet who does not want to see true poetry lost amidst the “flood” of poor poetry being produced today. Continuing his support for Darwish and his critical comments on modern poetry, al-Samarai states that Darwish inspires readers to re-evaluate what constitutes “great” poetry and to help end this “flood” that has obstructed the reader’s creative outlet.

A Few Words Go A Long Way

Perhaps critics like Beydoun, Bezzoun and Awit are correct in accusing Darwish of being too general and not providing a critical examination of modern poetry; however, we cannot forget that a weak tradition of poetry criticism exists in the cultural pages of Arab newspapers and magazines. “Here we find critics, authors and editors forming shilaliyya (cliques) and praising one another rather than offering insightful, critical analyses. In light of this weak literary tradition, demanding that Darwish be detailed and specific is a bit unreasonable, especially as this demand is not made of others,” said one editor who is familiar with the Arab cultural world.

Despite the criticism of Darwish’s statements, his words are likely to do more good than harm for Arab literature. Perhaps we need as strong a voice as Darwish’s to break the silence and infuse life into the tradition of literary criticism of modern Arab poetry.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 11, Nos. 50/51, Winter/Spring 2005.

Copyright © 2013 AL JADID MAGAZINE