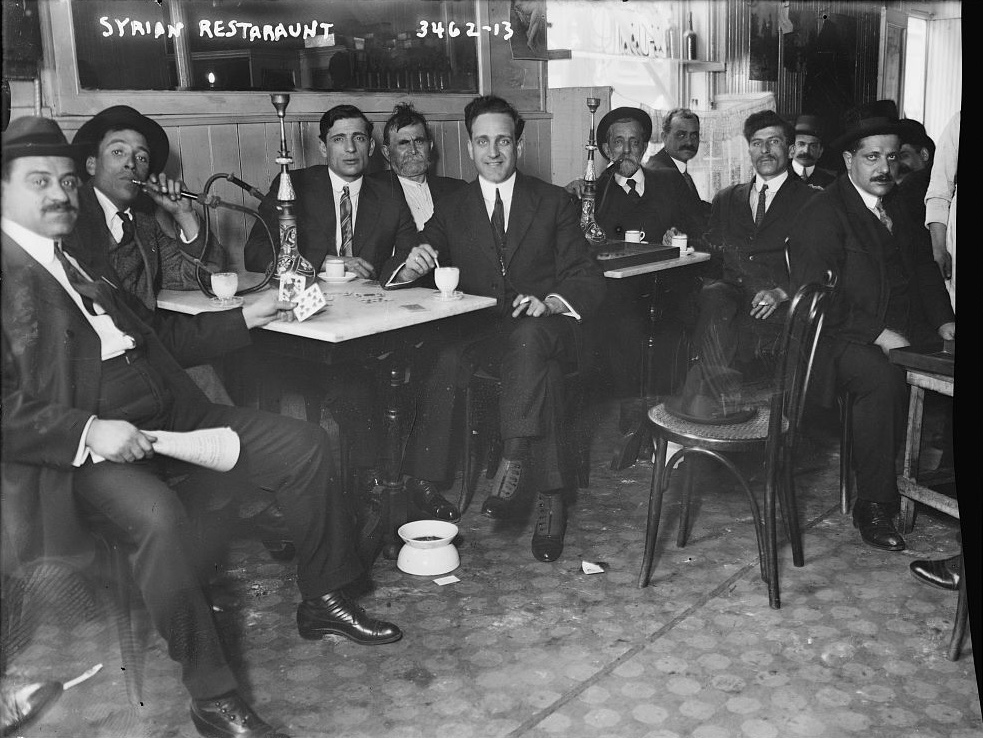

Between the Tunnel and the Tower:

The Afterlife of Little Syria in American Urban Memory

Pockets, though sparse, of Manhattan’s Little Syria have withstood the test of time, though just barely. The community was once considered the “mother colony” to the thousands of Arab immigrants coming from the then-Ottoman-controlled Greater Syria (which today encompasses Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and Jordan) during the Great Migration from 1880 to 1924.

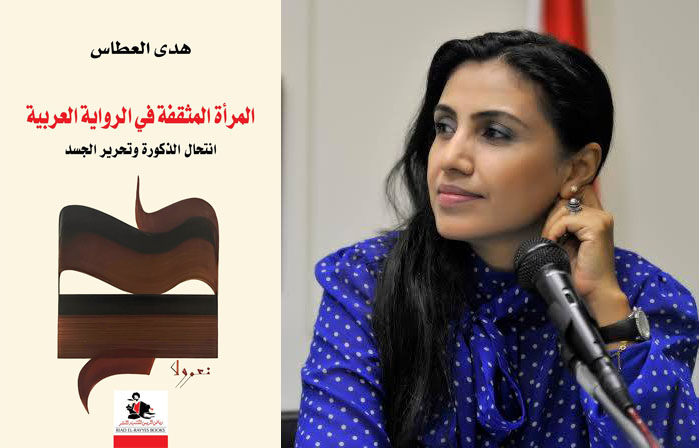

Hind, or the Myth of Beauty:

Hoda Barakat and the Mythology of Loss in Lebanon

Between living in the memory of beauty, deliberately blind to its flaws, and living in beauty’s shadow, perpetually weighed down by the past, Hanadi’s story is a portrait of more than a woman disregarded by both family and society, but an encapsulation of all the problems plaguing Lebanon, in fiction and reality.

A ‘Narcissistic Wound’:

Betrayal and the Politics of Survival in Syria

Syrians have nursed a wound that has never been given the chance to heal, just barely scabbing over before it is reopened once more — so much so that the Syrian experience has become synonymous with pain and suffering. In the aftermath of the coastal massacres in March, Samar Yazbek found herself feeling empty, searching for answers only to be met with silence.

Mourning the Swallows of Ghouta:

Twelve Years of Grief, Silence, and Betrayal

Twelve years have passed since the horrifying attack on the people of Damascus’ Ghouta district, but the nightmares of that day are just as vivid today as they were over a decade ago to the survivors. Shortly after midnight on August 21, 2013, Bashar al-Assad’s regime launched a sarin gas attack on the towns of Zamalka, Ein Tarma, and Irbin.

The Minimalistic Words of Sonallah Ibrahim:

A Hemingway Legacy Exposes the Rot Hidden Within Egypt’s Shadows

One of the Arab world’s most unyielding literary dissidents, Sonallah Ibrahim (1937-2025) devoted his life’s work to social justice and national liberation. Known for his stubborn integrity, Ibrahim refused to “enter the pen,” a phrase he used in reference to submission to the cultural establishment, and equally refused prizes, honors, and official recognition. He paved the way as the pioneer of the Arab documentary novel, his writing both a witness and a staunch refusal to submit to corruption and tyranny.

The End of Innocence:

Fear, Violence, and Lebanon’s Collapse of Moral Order

As an academic and editor who regularly follows news and interviews from the Arab world, I am often struck by a recurring line of reasoning in discussions of the Arab-Israeli conflict: Israel, some argue, does not need a reason to attack, because aggression is inherent to its nature.

This memory came back to me while reading Marwan Harb’s recent article in Al Modon, “Preventive Killing: No One Is Innocent.”* Harb reflects on the erosion of “innocence” a

Broken Branches:

Lebanon’s Empty Institutions and the Architecture of Collapse

Many debates on Arab politics revolve around the absence of institutionalization as a root cause of underdevelopment, corruption, and authoritarianism. This absence is often contrasted with the prevalence of personal rule — the dominant form of governance in much of the Arab world. Leading scholars and analysts have long emphasized the urgent need to shift Arab politics away from personalism and toward institutionalism, where laws, not individuals, determine the course of governance.