Khalil al-Neimi Exposes What Tyranny Has Done to His Homeland

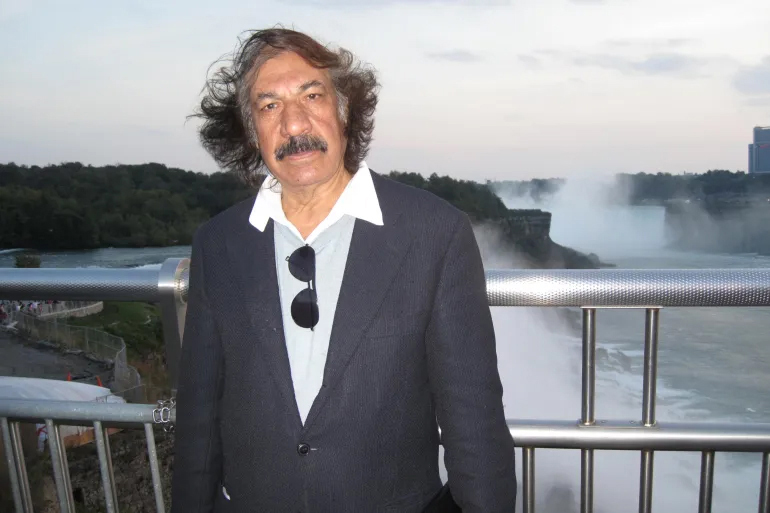

Photograph of Khalil al-Neimi from Al Jazeera.

I feel an affinity with Khalil al-Neimi, the author and novelist. Like him, I left my country, Lebanon, in 1972, and often thought about what I left behind. I gradually lost the desire to return, and later, after making a short visit back, I gave up on the idea altogether after being away for 38 years. Neimi and I differ on why it took us a long time to return (for me, 38 years, and for him, 50 years). It has been 53 years now since I departed Lebanon.

Neimi reflects on his return to Syria in his essay collection, “About a Country Once Called Syria,” published in three parts: Part I, “Disillusionment Once Again”; Part II, “History and Place”; and Part III, “What Tyranny Has Done to the World.”* Based on a theoretical distinction, I consider his time outside Syria an ‘exile,’ and mine a ‘diaspora.’ We have both witnessed our countries enduring brutal and bloody violence, 14 years for Syria and 15 years for Lebanon. In both cases, the human cost and physical destruction brought about by our civil wars were immense — tens of billions in physical and infrastructural carnage and hundreds of thousands in human casualties.

Neimi’s text focuses on memory, and for good reason. Memory plays a crucial role in preserving the essence of life and identity. Reflecting on past experiences, lessons, and knowledge empowers individuals and communities to overcome challenges and thrive. Memory ensures continuity, helping people learn from history; thus, it makes sense that some social scientists claim that memory is a form of survival. From personal experience, I am not hesitant to say that memory helps me recall both the positive and negative aspects of my past. Memory was inspirational; it helped me adapt to challenges and cope with new conditions in diaspora. Both Neimi and I experienced disillusionment upon confronting the harsh realities of our respective homelands. While Neimi's idealized vision of Syria was shattered upon his return, I, despite avoiding idealization, felt a similar sense of loss when I became aware of Lebanon's devastation during its civil war. This parallel underscores how disillusionment can arise regardless of one's initial perspective.

Neimi explores the paradox faced by many immigrants: the tension between leaving their homeland and the longing to return, often rooted in an existential desire for home. Social sciences examine this theme, showing how leaving can either serve as an escape or, unexpectedly, strengthen a person’s connection to their origins. This connection is sometimes reinforced by idealizing the homeland in its absence.

Psychoanalysis emphasizes 'lack,' or what we perceive as a missing element, as a driving force behind our desires. This theory suggests that desire is connected to the subconscious belief that fulfillment lies elsewhere. For many immigrants and refugees, "elsewhere" symbolizes freedom, wholeness, or a sense of harmony. However, neither departure nor return offers ultimate satisfaction, as their interplay sustains our existence.

American mythologist Joseph Campbell popularized the narrative structure used in literature, film, and mythology. This concept involves a protagonist leaving their familiar environment, undergoing a transformative journey, facing challenges, and returning changed or with expanded insights. However, returning is never the same — the place and the person have been altered. Perhaps this longing to return stems from a desire to reconnect with who we once were. Without stretching the comparison and contrast between myself and Neimi, when I returned, I also felt both Lebanon and I had changed.

People migrate from their homelands for countless reasons, driven by cultural, political, economic, and emotional needs and beliefs. Curiosity or dissatisfaction can also play a role, as well as a desire for change. Returning home reflects the lasting impact of one's origins, highlighting roots and their enduring influence on a person.

Memory distorts our perception of the past by romanticizing it and emphasizing its positive aspects. This results in a skewed version of what the past could have been, leading to an idealized view of the past. Consequently, the present seems inadequate in comparison.

The loss of a once-perceived 'captivating brilliance' may stem from a profound disconnect between individuals and their environments, shaped by disappointment and a tragic history. This alienation often occurs when tyranny's physical and emotional destruction erodes the enchantment once felt, leaving behind a lingering sense of irreconcilable misunderstanding.

Returning is a key theme in shaping identity and memory, highlighting the tension between an idealized past and present reality. Memory often romanticizes the past, creating a distorted lens through which the present is judged and found wanting. This idealization fosters a longing to return, not to the actual past, but to a version that never truly existed. This desire for return becomes a quest for identity, offering a sense of belonging or comfort that the present lacks. However, returning is inherently paradoxical — it seeks to reconcile idealized memories with a changing reality, often leading to disappointment or further distortion of the original experience. Ultimately, returning serves as a narrative of self-discovery, where the pursuit of the past reveals more profound truths about the present and the evolving self.

In his second essay, Neimi moves toward theoretical and intellectual analysis. The Damascus café symbolizes Syrian (and Arab) society following the collapse of authoritarian rule. Once defined by enforced silence, it now overflows with uncontrolled, chaotic expressions, pedantry, pretense, and empty discourse. This reflects decades of intellectual and emotional trauma. Its absurdity mirrors existentialist theater, where meaning is unattainable. The café reveals a cultural pathology: what occurs when a long-muzzled society gains its voice without processing its trauma?

The chaotic transition of Syrian society from enforced silence under authoritarian rule to unprocessed trauma is symbolized by the Damascus café. This cultural pathology, characterized by existential absurdity and intellectual dysfunction, reflects decades of emotional and philosophical trauma. The absurdity of the café mirrors existentialist theater, in which meaning remains unattainable, raising a critical question: What happens when a long-muzzled society gains its voice without processing its trauma?

As mentioned earlier, Neimi connects hollow claims to despotism, which suppresses reason and perception after years of tyranny. Unrestrained expression, accumulated fears, and a sense of meaninglessness now dominate the Damascus café, likened to "absurd theater."

The psychological aftermath of liberation, often referred to as post-repression disorientation, reveals a profound rupture between speech and meaning. This disarray stems from the accumulated trauma of repression, distorting communication to the point where truth becomes indistinguishable from falsehood, and sincerity from performance. As values collapse, individuals are left adrift in a world that feels simultaneously familiar and alien. Navigating this existential confusion requires a slow, often painful process of relearning, frequently marked by missteps and misdirection.

Neimi's sadness reflects both physical and psychological effects on people and places. His second essay delves into the irreversible loss of time, regret, and the melancholy of revisiting a place where meaning and memory have faded. Written in an elegiac tone, the essay mourns the undoing of a cherished city and country due to war and years of eroded truth and dignity. It raises the question of whether recovery is possible after such repression.

Neimi critiques those who avoid confronting reality through performance or rhetoric, prioritizing truth over historical context. This perspective advocates genuine engagement and truth-telling, even when it is difficult, as an ethical imperative against distortion and confusion. He firmly supports truth-telling as an ethical stance, regardless of discomfort or incompleteness, promoting sincere engagement and moral clarity.

The Arab World is reflected in Damascus, where Neimi portrays the broader Arab condition as characterized by stagnation, repression, sudden upheaval, and existential dislocation. The Syrian catastrophes, both distinctly local and universally Arab, exemplify structural failures in governance, imagination, and human dignity throughout the region. This gives the essay significant political and philosophical weight, suggesting that Syria's collapse serves as a cautionary tale for other societies.

The author’s idea is that Syrians' prolonged silence under authoritarianism has led to a form of speech that, while abundant, lacks depth, clarity, and meaningful purpose. It questions whether this speech truly reflects the experiences and suffering of the Syrian people. Neimi's analysis explores whether freely expressed speech, which reveals everything, holds any significant meaning. It raises questions about the topics discussed, the standards for judgment, and whether Syrians, after years of repression, are genuinely listening to their suffering. He suggests that their speech, although excessive, may lack clear purpose and sound judgment, thereby challenging its true significance.

The author’s central question, shared by many others, is why he returned to Damascus — a city that now symbolizes the decay of being and place. He refuses to deceive himself or pretend to be someone he is not. Instead, he prioritizes truth over historical narratives, believing it is essential for progress. He wonders whether the words he struggles to understand relate to what has been repressed and expressed in silence. Can he comprehend these words, given their repressed history?

Neimi’s third essay, “What Tyranny Has Done to the World,” is a reflection on the transformation of language and its emotional impact in Damascus, highlighting the broader societal changes during his 50-year absence. He observes that language has become more complex and exhausting, losing its former emotional resonance, which mirrors the shifts in the city itself. "I cannot believe I am now in Damascus," he remarks, "Not only have the faces changed, but the language has also evolved."

According to Neimi, "Language is not one-dimensional. It contains many joints, pathways, emotions, and shifts." He identifies the changes in Syria’s language, noting that “People now speak in a way that exhausts the listener before stirring their emotions like it once did."

Neimi asserts that 50 years of despotism have fundamentally altered both life and its expression. Despotism has reshaped individuals, diminishing their affection and warmth. Essentially, tyranny has stripped Syria of its core identity, leaving behind irreversible changes. This transformation extends metaphorically, as control over physical spaces, like mountain peaks, mirrors the dominance over thought and freedom.

“Damascus today stands as a dusty skeleton devoid of life, drained by a malignant tyranny that has regressed from it by a century,” he writes, stating that his over half a century of exile has developed within him a ‘cosmic vision’ that enables him to blend in with the silent beings around him seamlessly. “These individuals walk endlessly and aimlessly, as if moving itself has become their existential purpose...it seems like they were once even forbidden from moving,” he observes. Damascus, in the 50 years of his absence, has become marked by overwhelming destruction, sorrow, and a sense of alienation. Neimi reflects on the misery of the people and the loss of their old world, with only the sun, land, and distant shadows remaining constant. They question their return and struggle with a sense of disconnection from both the place and themselves. Damascus, as he once knew it has been replaced by a scene of desolation, neglect, indifference, and a “pervasive fear that has severed human connections,” states Neimi.

In attempts to reconcile the reality of the city’s transformation with the memory of what it once was, Neimi blends observation with introspection, reality and imagination with the vivid descriptions of physically and emotionally bleak landscapes. His recollection of "Victoria Bridge" and desire to see Damascus "with my eyes, not my imagination" implies a tension between reality and memory, leaving the reader to question the boundary between the two.

Neimi goes on to describe the silent and dangerous process of "emptying a place" such that the only remnants of Damascus are of tyranny and decay: an oppressive atmosphere, the remnants of a fallen regime, and the devastation that persists. He emphasizes the need to acknowledge and speak out against this human catastrophe. “The generalized decay left by the now-defunct despotism stuns me beneath the oppressive sun as I contemplate the void,” he writes, adding, "Tyranny devoured everything here and erased life's traces, even from life itself." His thoughts linger on the city’s lost charm and how its inhabitants interact with this changed Damascus: “Suddenly, I begin walking — seeing myself as two beings: one who walks, and another who observes the void, murmuring in grief, ‘What has tyranny done to the world?”’

In conclusion, Neimi's writing explores the irreversibility of time and the permanence of loss. He emphasizes that what has passed cannot be restored, whether through words or silence. His essay highlights the emotional weight of unchangeable changes and the futility of trying to reclaim lost opportunities or moments. Focusing on the psychological and emotional toll of repression, he examines confusion, disorientation, and loss. Using the metaphor of a "soul trapped," he illustrates the lasting impact of tyranny and the psychological confinement it imposes. His reflection concludes with a question that underscores despair and futility, offering a philosophical lament on life after tyranny, devoid of nostalgia.

*Khalil al-Neimi’s essays, “About a Country Once Called Syria: Disillusionment Once Again (Part I)”, “About a Country Once Called Syria: History and Place (Part II),” and “About a Country Once Called Syria: What Tyranny Has Done to the World (Part III)” were published in Arabic in Al Quds Al-Arabi.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 123, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE