Essays and Features

While much of the country — and even the world — focused on the last U.S. election and remained engrossed even after its results and consequences, the picture of this historic event in the Arab world was unlike anything that was happening here. Regrettably, the distorted analysis and coverage by Arab media influenced to some extent the attitudes and electoral choices of many Arab immigrants in the U.S.

Nawal El-Saadawi’s ‘Daughter of Isis’ Life and Times via the Plenitude of Her Writings

Rose Antun: Early 20th Century Arab Feminist Journalist

How ‘Shwam’ Migration Contributed to Arab Renaissance Movement

A new biographical book enriches the scarce literature on 19th and 20th century Lebanese and Syrian emigrants (often referred to as Shwam) who settled in Egypt and grew up to be journalists and intellectuals. Many of their contributions to the Nahda reflect the inescapable truths about the role of women in the Arab Renaissance movement.

Did Assad Use Beirut’s Port To Prosecute His War Against The Syrian People?

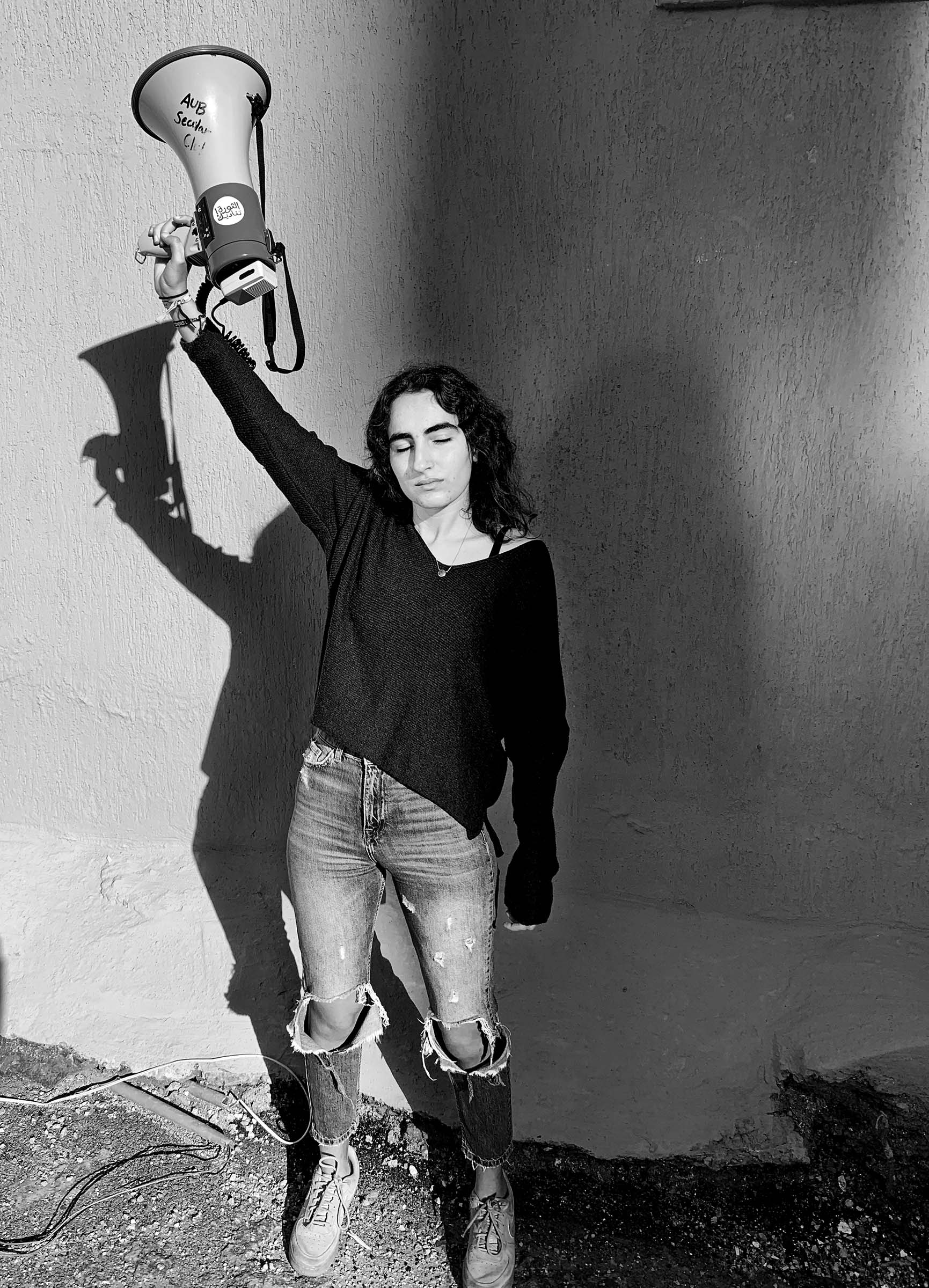

Despite a Bloody Decade of Conflict, ‘Heirs’ of the Arab Spring Are Blossoming!

A Nation in an Expanding Mental Ward: Poet Abdo Wazen Asks if Lebanon Is Now in Chekhov's 'Ward No. Six'

Rose Antun: Recognizing the Contributions of Long Neglected ‘Shwam’ Feminist Journalist to Arab Nahda

ESSAYS & FEATURES IN FORTHCOMING AL JADID, VOL. 24, NO. 79, 2020

Rifat Chadirji (1926-2020): Architect Who Integrated Traditional Iraqi And Modern Architectures, Then Turned to Life of Writer and Scholar

Many Historic Buildings and Cultural Sites Destroyed in Beirut Explosion: Did the Blast Fatally Tear Lebanon’s Cultural Fabric?

The ‘Grand Compromise’ Between Lebanon’s ‘Strong Presidency’ and Iran’s 'Rejectionists' Hastens the Demise of Lebanon’s Economy

In early July, we wrote about two suicides in Lebanon while holding off on a third until we fact-checked it. Subsequently, the Beirut-based Al Modon newspaper wrote about a total of four suicides, including the two reported here. The article’s author deliberately stressed the reasons behind the suicides were not personal, but rather related to deteriorating economic conditions and the loss of dignity.