Would you please introduce yourself, and give us some idea of your background?

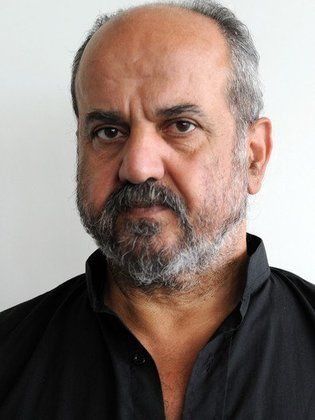

My name is Usama Muhammad. I was born in 1954 and am from Latakia, Syria. I graduated in 1979 from Moscow University as a film director. I wrote and directed some short films and worked in Syrian cinema with my friends and colleagues either as a scriptwriter, or in what is called in Syria an "artistic cooperation practice" in which two directors cooperate to make the film of one of them. I wrote and directed one feature-length film, "Nujum al-Nahar" [Stars In Mid-Day], which I consider my most important film. The film was made in 1988, and it was shown for the first time at the Cannes Film Festival in a special event called "Fifteen Days for Directors." The film then toured the Arab, European, and international film festival circuits. It won some important prizes, probably the most important is the "Golden Palm" prize in 1988 in Valencia, Spain. It also won some critics' prizes, which are very significant for me, especially the International Critics Award. Despite all this, it is very painful and unfortunate that the film has not reached its audience yet, the Syrian public. I frankly consider that eventual moment to be the most important moment for my film and perhaps for any film. Now, I am trying to make another film.

Would you please tell us something about your film "Nujum al-Nahar." What is the story of the film?

I think this is a very hard question to ask of any director. The visual presentation is much richer than any narration of a film's plot. As you know, there is more than one perspective or point-of-view on every scene, and any scene can be felt and interpreted profoundly in two, three or four different ways, in addition to the different social, political, and historical interpretations. Telling the story of a film is like mixing eight tapes of sound effects in one tape, and I do not think this would be fair to the film. But sometimes I like to say that my film is about illusions in general, and in particular the illusion of belonging to a power or an authority. It is a demonstration of a boiling point, a crucial moment in some people's lives - average people who detached themselves from their natural environment thinking they would be better off and grow stronger by following a different path in their life. Let me read you something which was written about the film. "The film has a sarcastic style; it is full of violence, full of the harshness of love. It is a black comedy - a wedding smells of the aroma of a funeral; a family sets up festivals and rituals for its union and strength, but it turns into a divided swollen mass of words, slogans, and high flying emotions ignited by the light of freedom, which is hidden behind the ribs of the most marginal and spontaneous characters in the film. Those who were forced to enter the pen to glorify the dream of the group are not allowed to exercise their right to a personal dream. They are the ones who demolish the pillars of the festival. The sister escapes on her wedding night. The deaf brother slips away from the emotional walls which imprisoned him, fleeing to Damascus, rushing towards his illusion of freedom and his personal dream. Deaf, he is lost amidst the noise of the capital and disappears in the fog of the snow-white insecticide."

Talking about authority, you and other directors in Syria have the opportunity to make films which are considered from the opposition school. What kind of a relationship exists between intellectuals and artists and the authorities which make it possible to produce such films, although some of these films are not shown in Syria?

I think here we have to talk about the process in which culture and art are, or are not, produced. This process is very complicated and I do not think it can be described or explained in a few words or in a simple way. As a matter of fact, we literally do not have any laws or rules which regulate the artistic or cultural process. Cinema is administered by the government, and there are laws that allow only the government to import films. But there are no laws which restrict the production process either privately or publicly. For many reasons private production these days is almost dead, maybe because it found in television an easy and lucrative outlet. We have a structure which allows us to produce films, although this production is not enough to satisfy the needs of the local market. My colleagues and I work through the available channels, and as I said earlier there are no rules to restrict our work. In principle, everything is allowed and possible until the moment of censorship, when permissions are given or withheld, either partially or completely, for a film. In general, I can say that what is allowed is much more than what is prohibited, and I personally think it is not necessary for cinema to always tackle the government in its high profile as a subject. I think the most important issues for art are society and the human being, the human structure of society. I do not want to theorize about art and what it should or should not say, but this is my own opinion. I think it does not matter how many governments come and go, the human structure of a society, from a backward society to a developed one, cannot be changed overnight following a change in government. The traditions of society and their legacy on existing social, psychological and economic problems, and their effects on the human being provide a substantial field for art to explore deeply and to engage with profoundly, regardless of any existing authority.

As filmmakers, we work according to a system which is basically very similar to the one which was followed in the Soviet Union, whereby there is governmental cultural administration of artistic and cultural production. There are specialized committees, "Intellectual Committees" or "Creative Committees" who accept or reject scripts. These committees have been, throughout our historical experience with them, very receptive to accepting scripts which contain high critical vision. The production of most of the important Syrian films was possible because these "Intellectual Committees" gave them the necessary go-ahead. But we have to admit that at the same time that we have the opportunity to produce our films and to express our own critical vision in these films, we might sometimes have interference coming from outside this artistic mechanism, which bridles the creative process.

Syrian films are well known for their uncompromising critical vision and this has become a very respected feature of Syrian cinema. Therefore superficial or bad films are disrespected and are outcasts in our cinema; these works are usually shunted off to television. I think Syrian filmmakers have drawn the initial distinguishing features of their cinema - a respected and serious cinema.

"Nujum al-Nahar" was seen by foreign, Arab, and local audiences, and no doubt you received different comments about the film. Which ones interest you the most?

What attracts my attention are the different readings and interpretations of the film, especially when these interpretations emerge out of small details to reach the general public. In Europe, for example, in France, Italy and Spain, and even in Canada, people are inclined to understand the film through the lens of city-country dichotomies and tensions.

In the Maghrib, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, the film was interpreted as a discourse about Arab unity. Therefore, it was received with great enthusiasm. The Maghrebi spectator did not see the film as a Syrian film, instead he or she considered it his special film. The differences in interpretations of the film is what I consider most important, and I see in this difference some compliment to the film. The film has garnered very interesting critical reviews.

The French magazine Liberation considered it "miraculous." Some people, such as Tawfiq Saleh (the well-known director), considered it the best film for 1988, for example, and others have considered it a disaster.

In "Nujum al-Nahar" there are some scenes and images that do not reach the average spectator, or even the educated one; they seem to be directed to film professionals. Should we sacrifice the average spectator for the professional one?

There is a language which brings the average spectator, the educated one, and the professional one all together. It is the language of feelings and emotions, and I trust this language and trust the spectator. This question has a long historical precedent, and I know that neither Imru al-Qays, nor al-Muttanabbi, ever accepted to substitute their words for ones that were understood by everybody. Of course we are talking here about masters in literature. But we all know that there is something called "the unattainable simple language," and please allow me to fancy that I have that language in my film until I meet the average spectator, and, by the way, I still miss that average spectator a lot.

You depended on diversity in choosing your actors; some of them were acting for the first time, others were new graduates from The High Institute of Theatrical Arts, and the rest were professional actors. Why did you choose this diversity and did you encounter any problems?

Basically I was not looking for diversity; I was looking for the film's characters, for their sounds and pulses. There was some resonance coming out from a special intuition telling me to stick with this actor with all my strength and patience, or to pass by another one in spite of the admiration I may have for him or her. That was my criteria for choosing the actors, and as a result the harmonious carpet was created by professionals, new graduates, and those who were involved in acting for the first time.

Now, after the film has been made, I can say that all of them created a very special and admirable flavor in that film. They broke through the traditional and the frozen in their understanding and performance of their characters.

It has been said that short films are very good practice for filmmakers, and you had successful experiences in that area after your graduation. When do you think a filmmaker can benefit from his work in short films, especially if he does not have the chance to work in a feature film?

A filmmaker can benefit even from his daily walk on the street. He can benefit from short films, or even from his daydreams. But working professionally in film has more potential to develop the filmmaker because it intensifies his relationship to reality, his profession, and himself. It also raises many questions about the relationship between these three factors. Talent and quality take first place, of course. One time Eisenstein, who was the Dean for the Cinema Institute in Moscow, was asked, "How can you determine who can be a director and who cannot?" He answered, "Every one can be a director, with a little difference; some people need five years and others need five thousand years."

In Arab and International cinema there are many names and schools. What are the names or the titles that attract you, and what kind of a relationship do you have with cinema?

In the past I used to say that Italian cinema, then Georgian cinema attracted me. I like Fellini and Escola. I love their films because they are full of life, philosophy, and beautiful sarcasm. I love sarcasm in general, and in particular the tragicomedy. I think the sarcasm in Fellini's work is the maturest and it is always mixed with fascinating romanticism.

But I do not know why I am not, any more, very enthusiastic about Italian cinema or any other cinema. Today I am fond of films from everywhere. I think these days we are in the era of directors and films as individuals. I do not think that Italian cinema is offering today the same quality or quantity as it did in the past.

Today, when you see a film from the former Yugoslavia directed by Emir Kostarica, for example, his films contain Fellini and Escola, beside encompassing elements from both American and Yugoslav cinema. But then I see a film from a director who presents his own vision and this goes to the top of my list. In the next festival or event this film might be Chinese or Arab, etc.

There is better understanding and appreciation for cinema these days, and now the director who has a real and profound subject, in addition to talent, is taking the lead.

Therefore I look forward to Syrian cinema and to what it can present with a lot of confidence and faith. I think my international tour with my film "Nujum al-Nahar" made me shake off any illusion or inferiority complex, and I can say that Arab and Syrian film directors, I mean our friends who drink coffee in the coffee shops of our Arab capitals, have all the potential to make the world hear their voices, our voices, our concerns, and our tones.

I am clearly inclined to believe emotionally and intellectually in my friends and in their experiences, because I always learn something from them. They have all the talent, the interest, and the depth, in spite of all the problems: gas, tires, and small budgets.

As for my relationship with cinema, it is a love relationship in all respects.

When we talk about the qualities of a film we mean the technical, intellectual, and artistic qualities. In many cases technical and financial capabilities cannot rescue a bad film. To what extent can we ignore the technical and the financial factors in the process of making a good film?

High technical capabilities are very important in making a good film, and I do not think that film technology is secondary any more. Without this technology you cannot compete with others and reach international screens. Nobody is interested, these days, in a film with bad colors or poor sound effects. I think ignoring technological developments will lead to decline. It is based on a crude understanding of cinema and the relationship between the outward and the substance.

The face of a beautiful girl lit-up and filmed according to certain conditions is an integral part of the main idea and not a fantasy to be imagined by the spectator. There is a big difference between talking about heaven and going to heaven.

The cinema of content or the cinema of struggle and propaganda is over; nobody sees it or makes it anymore. That period had ended. I consider the call for a cinema without well planned budgets or without good actors a stupid call.

You belong to the second generation in Syrian cinema; the first generation started in the 1970s. What do you think about the accomplishments of these two generations, although the number of accomplished films is considered small in comparison with the number of filmmakers?

Syrian film is very rare in the Syrian film market, due to several factors. First, the number of films produced annually is very small, it ranges between one or two films per year. Second, we do not have a real film market. We have around eight movie theaters in Damascus, poorly equipped except for one or two in a five star hotel, meanwhile there are seventy or eighty theaters in Tehran, although we might have a different idea about Tehran. Distribution and marketing is another problem; until now we do not have an organized distribution process for Syrian film.

Therefore, Syrian cinema has not been able to build and accumulate a relationship with its spectator. It cannot stay in the audience's memory, which is occupied, most of the time, by American, Egyptian, or Indian films.

But if we talk about the quality of Syrian film, I think that we have a very important achievement. Even though the number of Syrian films was and is still very small, these few Syrian films have resulted in very special recognition and respect for Syria cinema, and made critics in Arab and international film festivals await new Syrian films and the work of Syrian film directors. The difference between our achievement in the international film world and our achievement in our own country is striking.

The director was interviewed while in the United States to attend "The Centennial of Arab Cinema" where his film, "Nujum al-Nahar," was shown.

The interview, conducted in Arabic, was translated into English by Gabriel Kartouch, a Syrian-American translator, and member of the American Translators Association. (Alia Arasoughly also contributed to this interview.)

This interview appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 14, January 1997.

Copyright © 1997 AL JADID MAGAZINE