Reading ‘The Life Before Us’ Across Borders

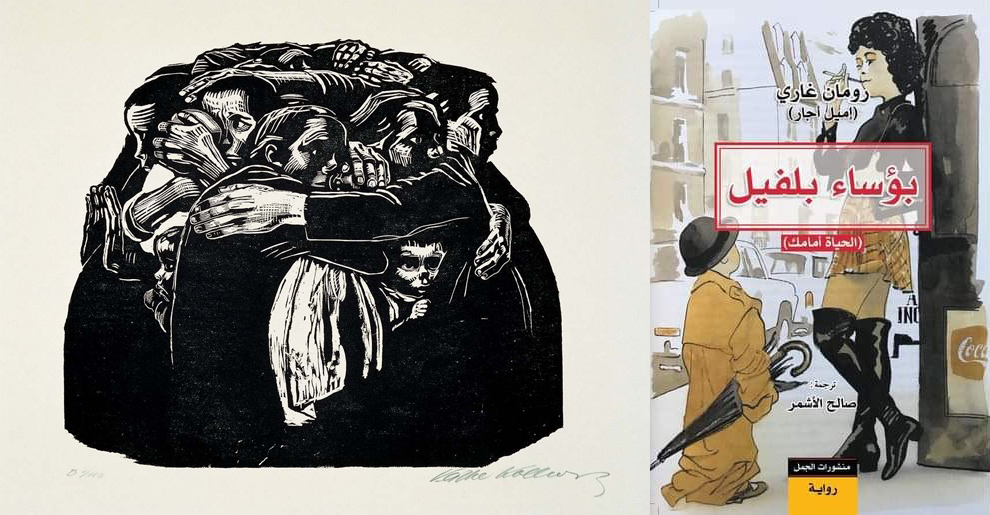

On the left, “The Mothers” (sheet 6 of the series “War,” 1921-1922) by Käthe Kollwitz from the Cologne Kollwitz Collection courtesy of the Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln. On the right, the Arabic cover of “Les Misérables de Belleville” (Dar al-Jamal, 2021).

When an unknown author claimed the Prix Goncourt in 1975 with his novel “The Life Before Us” (La Vie Devant Soi in French), news media scrambled to unravel the mystery behind the bestselling book and its writer. After a man claiming to be its author, Émile Ajar, accepted the prize at the awards ceremony, the matter was thought to be closed — yet the truth surrounding the authorship of the novel would only fully emerge five years later in the will of the late author Romain Gary, in which he confesses he was the real writer behind the pseudonym Émile Ajar and that a relative had posed as Ajar at his behest.

Since then, “The Life Before Us” might be remembered for its mystery writer, or the fact that its author Romain Gary won the Goncourt twice (first in 1956 for “The Roots of Heaven,” originally published as Les racines du ciel, and second with “The Life Before Us” in 1975), spurring controversy as the only writer to have done so. According to his will, Gary published the novel under a pseudonym “to test his own literary merit, to see whether readers would judge the world on its own, free from the influence of fame,” as stated by Said Khatibi.* Muhammad Nasir al-Din suggests in an essay, “Romain Gary: Les Misérables de Belleville,” published in Al-Akhbar, that Gary published under Émile Ajar because of literary battles among French critical circles that questioned the quality of his novels.** Nasir al-Din adds that Gary’s lawyer, Gisèle Halimi, explained that the author refused the prize “for personal reasons related to peace of mind and a desire to escape the limelight and fame. Major newspapers criticized this stance, but the Goncourt committee stood by its decision, arguing that "the prize was awarded to a book before its author."’

For Arab and Algerian readers, the novel stands out for other reasons, remaining a timeless and captivating story that reflects the life of a North African Arab boy and his experience as an immigrant in France. The novel was published in Arabic in 2021 under the title “Les Misérables de Belleville" (Bu’asā’ Balfīl, Dar al-Jamal), translated by Saleh al-Ashmar. In the 1970s, at the time of the novel’s publication, the newspaper Le Monde ranked it 17th among the 100 best novels read by the French. The novel has been adapted to film twice, in 1977 and most recently in 2020.

Set during the 1970s, the story follows the life of Momo (a nickname derived from his full name, Mohammed), a young boy of about 10 years living in the Belleville neighborhood of Paris. Knowing neither his origins nor his family, the boy grows up under the care of Madame Rosa, a retired Jewish prostitute and survivor of Auschwitz who settled in France and converted her top-floor flat into a secret daycare center for unwanted or abandoned children, often the children of other prostitutes. Momo’s parents — his mother likely Algerian — entrusted the boy to Madame Rosa when he was three years old. Through Momo’s eyes, readers witness aspects of the immigrant experience that may seem too dark or mature for a child’s eyes, yet Momo takes it all in stride.

Madame Rosa may not be a perfect caretaker, but she undoubtedly brings an earnest, human quality to the narrative. Momo describes how she differs from other women who run similar daycare services in their neighborhood; unlike others who would sedate unruly children, she did nothing to harm the children, choosing instead to use tranquilizers on herself. He explains in the novel: “When we were agitated, or when we had seriously unruly children during the day — and such things existed — she was the one who would sedate herself. Then we could shout or fight, and it wouldn't even reach her ankles. I was the one who had to enforce order, and I liked it very much because it made me feel superior. Meanwhile, Madame Rosa was sitting on her sofa, her tummy covered in a woolly frog that contained a hot water bottle, her head slightly tilted, looking at us with a lovely smile. Sometimes she would even wave her hand at us as if we were a passing train. At those moments, there was nothing we could learn, and I was the one in charge of preventing the curtains from burning, which was the first thing we burned when we were young.”

Despite its rather comical tone, the novel does not shy away from serious or darker topics, offering insight into Madame Rosa’s experience as a survivor of the Holocaust as well. As Momo explains in the novel, “The only thing that could rouse Madame Rosa while she was under the influence of sedatives was the ringing of a bell. She had a terrible fear of the Germans. It’s an old story, mentioned in every newspaper, and I don't want to go into details, but Madame Rosa still lived with it. Sometimes she thought it was still happening, especially in the middle of the night. She was someone who lived on memories,” as cited by Nasir al-Din.

Not just a guardian to the other children, Momo eventually becomes a guardian even to Madame Rosa, as she begins to forget herself with age. He poses as a 14-year-old boy to qualify as Madame Rosa’s caretaker, allowing her to remain in her home instead of being sent to the hospital. As her closest companion, the boy stays by her side as she grows older and begins to forget the details of her own life, sharing stories about his days wandering the streets, trying to survive, and about her life as well. In the words of Saleh al-Ashmar, the translator of the Arabic edition, “He also talks about the neighborhood’s residents, the unhappy immigrants who came from Africa, Algeria, Morocco, and elsewhere to sweep the streets of France…and also the anguish of mothers who would come to check on their children and then disappear without a trace.”***

Though a French novel, “The Life Before Us” resonates especially closely with the Algerian and immigrant experience. As Khatibi writes in his essay “A French Novel That Tells an Algerian Story,” the novel “perfectly mirrors the Algerian condition today. It is a French story that could easily be read in Algeria as a local tale — one that describes our reality better than we might tell ourselves.” He adds that Algerian readers might feel a sense of familiarity with the story through its narrator Momo, who witnesses life in France as a North African Arab, from the resurgence of racism to the suffering of migrants, all through “the gaze of an outsider who himself is seen as the ‘Other.”’ Khatibi continues, “The crises it explores are the same that preoccupy readers in Algeria today: poverty, orphanhood, social conflict, the coexistence of difference, the struggles of women, and the lives of abandoned children.” A memorable story for more than just its mysterious origins, “The Life Before Us” remains a scathing critique of France’s treatment of immigrants and those living at the lower end of society, from the poor to the elderly.

*Said Khatibi’s essay, “A French Novel That Tells an Algerian Story,” was published in Arabic in Al-Quds Al-Arabi.

**Muhammad Nasir al-Din’s essay, “Romain Gary: Les Misérables de Belleville,” was published in Arabic in Al-Akhbar.

***Saleh al-Ashmar’s essay, “Les Misérables de Belleville,” was published in Arabic in Al Mayadeen.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 144, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE