The Afterlife of Little Syria in American Urban Memory

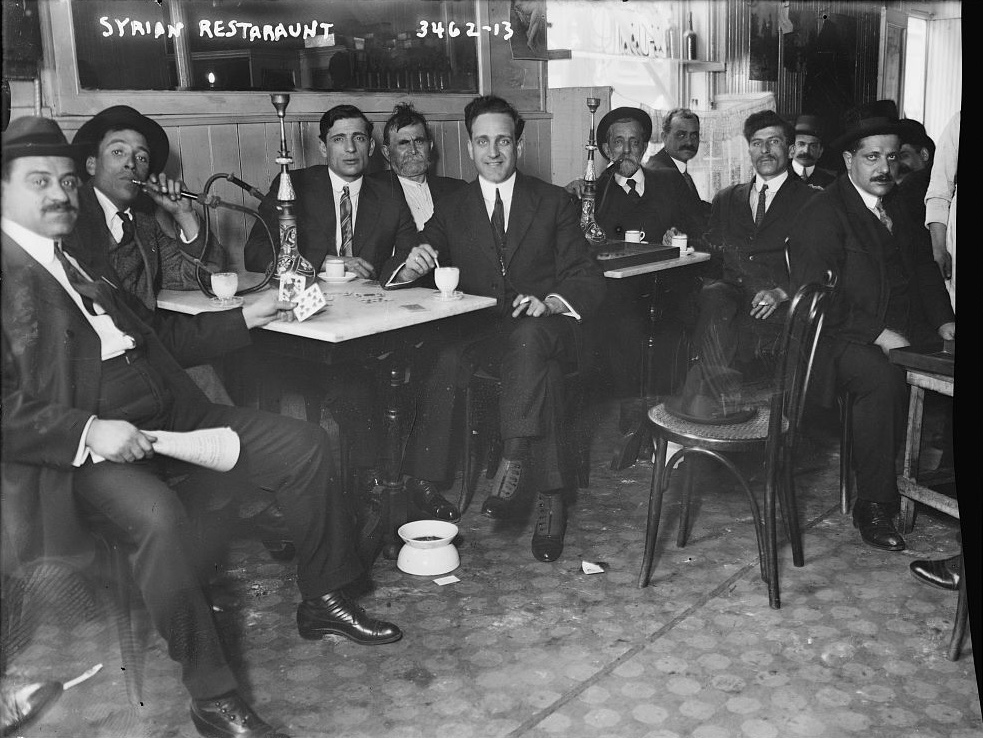

A Syrian restaurant in Little Syria, photograph from the Bain Collection/Library of Congress.

Pockets, though sparse, of Manhattan’s Little Syria have withstood the test of time, though just barely. The community was once considered the “mother colony” to the thousands of Arab immigrants coming from the then-Ottoman-controlled Greater Syria (which today encompasses Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and Jordan) during the Great Migration from 1880 to 1924. Though the neighborhood would come to be known as the “heart of New York’s Arab world,” as the New York Times described it in 1946, this legacy would come close to being completely erased in the decades after Little Syria and its residents were pushed off the map.

Little Syria’s story begins in the 1880s with the arrival of 95,000 Arabs to the United States. These immigrants settled in Lower Manhattan due to its proximity to the docks and its income opportunities. The neighborhood, located on the west side of Lower Manhattan on Washington Street and Rector Street, was home to the first Arab community in America. Syrian immigrants also established a community on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, which would eventually outlast Manhattan’s Little Syria.

According to historian Asad Dandia, Arab migration to the States was brought about by a decline in the silk industry, farming challenges, ethnic and religious tensions with Ottoman rulers, and recruitment from U.S. missionary schools, writes Jonathan Custodio in The City Scoop newsletter.* Writer and editor Gregory Orfalea, who authored “The Arab Americans” (Olive Branch Press, 2005), attributes the migration of Syrians, Lebanese, and Palestinians to “starvation, lawlessness, conscription, taxation, and religious intolerance at home; to proselytizing by American missionaries; and to economic troubles that led them to a new world where cultures existed, sometimes bruisingly, cheek by jowl,” as quoted by David Dunlap in the New York Times.** While outsiders referred to the neighborhood as Little Syria, its residents knew it as the Syrian Colony (as it was referred to in local newspapers) or the Syrian Quarter.

These newly arrived Syrians and Lebanese immigrants were mostly Christian, with 5% of the population made up of Muslims hailing primarily from Palestine. Historian Linda Jacobs writes in “New York’s Best-Kept Secret: Manhattan’s Syrian Quarter” that due to demands by the four religious congregations (primarily Maronite, Melkite, Orthodox, and Protestant) for Arabic-speaking priests to be sent to New York, each had their own priest by 1900 and opened a chapel in one of Washington Street’s tenement buildings.*** She states, “Several sect-based benevolent associations were founded to help their fellow congregants in need, but possibly as an antidote to this sectarianism, in 1909, immigrants founded the first and only Syrian Masonic lodge, where men of all faiths could and did mingle.”

Syrians, Lebanese, and Palestinians brought with them their trade, culture, and cuisine, setting up storefronts and living in settlements along Washington Street, where they also coexisted with the Irish, German, and Eastern European immigrants. The location was ideal for its proximity to the city’s docks, where most commerce and trade centered.

Upon stepping into Little Syria, one can only imagine the scents of shisha, baklava, figs, and strong coffee that once filled the air but vanished once the neighborhood was vacated. Syrian immigrants began as peddlers, selling a variety of wares and pastries that evoked memories of their childhoods in Damascus and Beirut. As Gregory Orfalea writes in “The Arab Americans,” Washington Street and Rector Street became “an enclave in the New World where Arabs first peddled goods, worked in sweatshops, lived in tenements, and hung their own signs on stores.” With their meat markets, silk traders, and textile shops, the district became a thriving commercial hub and was even referred to as the “lingerie capital” of New York, according to Queenie Shaikh in Independent Arabia.**** Women made up a major part of the community’s economic fabric.

The renowned Lebanese grocery store, Sahadi’s, was established in 1895 on Washington Street. Known then as A. Sahadi and Co., the business was run by its founder, Lebanese merchant Abraham Sahadi, his wife, Zakia, and other family members. The company sold groceries as well as brass lamps, arak, and other Middle Eastern goods. When most other Middle Eastern establishments in the neighborhood were forced to relocate in 1948 due to construction, the family-run grocery store settled down on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn.

Little Syria’s rich history is also tied to several iconic Arab American intellectuals and cultural, literary writing circles, among them Gibran Khalil Gibran, Ameen Rihani, and the Pen League, founded in 1920. Several Arabic newspapers and books were published in the 19th century, all “laboriously typeset by hand,” as the linotype machine was not yet adapted to Arabic until 1912, notes Jacobs. The first Arabic language newspapers in North America were printed in New York; Kawkab America (Star of America) was established on April 15, 1892 by two brothers, Nageeb and Abraham Arbeely, members of the first Syrian immigrant family to settle in the United States. Syrian and Lebanese writers and poets began to publish their works in newspapers and eventually produced poetry books, novels, and the literary magazine Al-Funoon, founded in 1913 by Nasib Arida. Little Syria became the neighborhood in which the linotype machine was finally converted to Arabic characters, revolutionizing Arabic-language journalism on a global scale, according to the New York Public Library.

Some journals, like Kawkab America, played vital roles in combating widespread misconceptions about Arabs, particularly Syrians. As Taissier Khalaf writes in “Welcome to ‘Little Syria’: A Missing Historical Piece of New York’s Ethnic Mosaic,” published in Al Majalla, common Western orientalist perspectives of the time depicted Arabs as “barbaric and culturally backwards.”***** In the words of Khalaf, “Arbeely — alongside other editors of the paper — would frequently publish articles that defended the dignity of Syrian and Arab communities, firing back against reports in the New York Times that described Syrian street vendors as 'dirty Arabs' or 'Arab thieves' who 'intend to invade the United States."

Little Syria began to fade with the imposition of strict quotas on immigrants through the Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act), which harshly limited both Asians and Arabs from entering the country. Syrian immigration was reduced to a mere 100 per year.

Meanwhile, many families chose not to settle permanently on Washington Street and set their sights elsewhere. From the mid-1980s through the 1920s, those who had prospered enough and could afford it relocated to Brooklyn instead, where more space, light, clean air, and access to good schools welcomed them, states Jacobs, who adds that while newly arrived immigrants still flocked to Washington Street, “these stayed for ever-shorter periods before leaving.”

Prospects for the district’s future took a definitive turn by the 1940s. New York urban planner and public official Robert Moses used eminent domain to demolish the buildings on Washington Street for the construction of the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel (better known as the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel). By this point, New York’s Arab American communities were primarily based in Brooklyn. Little Syria’s remaining residents received eviction notices in 1946, and “some residents clinging to the neighborhood were given just 24-hour notices to vacate their homes,” according to historian Asad Dandia, as quoted by Custodio. After the district’s demolition, new waves of Syrian, Lebanese, and other Arab immigrants resumed after the quotas enforced by the 1924 Immigration Act were lifted following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, settling in Brooklyn.

One writer recalls her family’s ties to the historic neighborhood. Alice Lesperance’s essay, “Manhattan’s Vanished Little Syria, and the Work of Preserving My Family’s History,” published in Catapult Magazine, shares her family’s roots in Little Syria beginning with her great-grandfather’s arrival from Syria in 1899.****** She describes an 1899 article published by the New York Times that painted the Syrian Quarter as the “tousled, unwashed section of New York.” In her words, “I learn a lot: that the vast majority of Syrian immigrants came to the United States from Zahlé or tiny villages nearby in Syria, as did my great-grandfather. I learned that, like my family, many of the larger Syrian families with money began to move out to Brooklyn, though many still worked in Manhattan.”

What remains of Little Syria is merely an echo. Three solitary buildings — the St. George Syrian Catholic Church, the Downtown Community House, and a tenement building — remain, having survived almost 80 years of urban planning projects and construction, though barely. In 2016, the Downtown Community House was practically beleaguered by buildings under construction, writes Lesperance. Built in 1926, the building served as lodging for newly arrived immigrants and was a vital center for community programs and providing food for malnourished children.

109 Washington Street, a famous tenement building built in 1885, is the singular remainder of around 50 other tenements that once lined the streets of Little Syria. Following the events of September 11, the building’s proximity to the World Trade Center garnered it attention online and in radio broadcasts.

The last building, St. George’s Chapel, once served as the main house of worship for Little Syria’s predominantly Christian community before it fell out of use. It then operated as a pub for 30 years and later as a Chinese restaurant. Both businesses have since closed. The church was built in 1812, converted into immigrant housing around the 1860s, and used as a place of worship between the 1920s and 1940s until residents were forced to leave the neighborhood. Though Little Syria was primarily known for its Christian population, the neighborhood also had ties to Muslim communities. A mosque once sat near St. George’s Chapel and was active during the district’s peak years before being demolished in the 1950s.

“These are places that had stood the test of time — testaments to where early Syrian immigrants lived, worked, and prayed,” writes Lesperance. “But most painfully, I think about all of the little buildings and shops that never made it to the 21st century, or even beyond the latter half of the 20th. I feel a sense of heaviness walking by where they used to be. I called my mom, who hasn’t lived in New York in decades, to tell her that the buildings were all gone, and she said nothing but, “Oh wow. Oh wow.”

Today, efforts to preserve the memory of this culturally rich neighborhood continue. Of the three remaining buildings, only the church is protected as a city landmark. Public officials, activists, and preservationists continue to fight for the preservation of both the community house and residential building as landmarks. Some have even taken matters beyond advocacy and directly to the streets; historian Asad Dandia frequently leads tours around the historic quarter, rekindling the image of Manhattan’s once-bustling Little Syria through stories and education. Despite the fragility of memory, extensive care has been taken in trying to preserve Arab American history, refusing to let it fade away in silence.

*Jonathan Custodio’s essay, “The Little Syria Tour Guide Bridging NYC’s First Muslim Settler and Mayoral Hopeful Zohran Mamdani,” was published in The City Scoop Newsletter.

**David W. Dunlap’s essay, “When an Arab Enclave Thrived Downtown,” was published in the New York Times.

***Linda Jacobs’ essay, “New York’s Best-Kept Secret: Manhattan’s Syrian Quarter,” was published on the Tenement Museum’s website.

****Queenie Shaikh’s essay, “How Little Syria Disappeared from Manhattan, New York,” was published in Arabic and English in Independent Arabia.

*****Taissier Khalaf’s essay, “Welcome to ‘Little Syria’: A Missing Historical Piece of New York’s Ethnic Mosaic,” was published in Al Majalla.

******Alice Lesperance’s essay, “Manhattan’s Vanished Little Syria, and the Work of Preserving My Family’s History,” was published in Catapult Magazine.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 142, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE