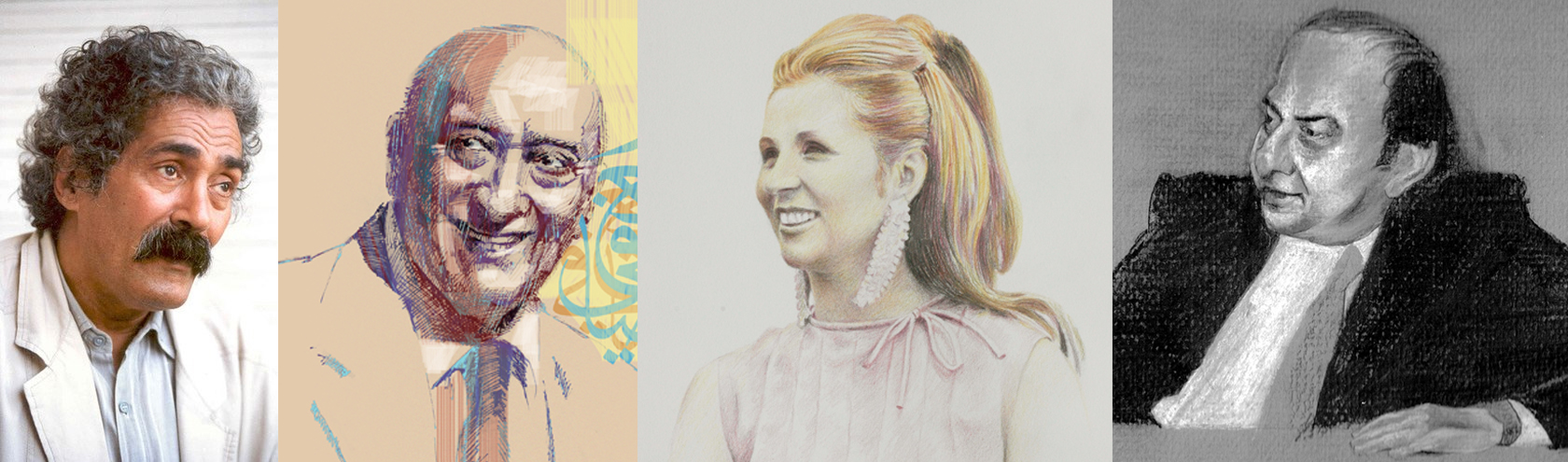

From left to right: A web-based photograph of Ibrahim Aslan; artwork of Wadi El Safi by Mamoun Sakkal for Al Jadid; artwork of Sabah by Zareh for Al Jadid; and artwork of Assi Rahbani by John Sayre for Al Jadid.

I grew up in Hazmièh, a small town east of Beirut, Lebanon's capital, during the early 1960s. Our rented apartment was situated near a modest multi-unit residential building, known as the Wadih El Safi building, named after the celebrated Lebanese singer who owned it. At the time, Wadih El Safi (1921-2013) was renowned for his wealth and fame, a reputation that endured after I immigrated to and settled in the United States. Wadih El Safi's later life is notable for his declaration of bankruptcy just a year before his death. He attributes his financial troubles to a monopoly contract he signed with Rotana, a Saudi Arabian record label and the music division of the Rotana Media Group.

Lebanon's iconic singer Sabah (1927-2014) spent her final years living in a hotel after selling her home and property. Critics attribute this turn of events to her renowned generosity, exploitation by friends and relatives, and her tumultuous romantic life. Her life was marked by instability, with eight failed marriages, each ending in divorce. Her last marriage, to the much younger "Fadi Lebanon," became one of her most tragic chapters, marred by bankruptcy, oppression, and scandal.

Assi Rahbani (1923–1986), along with his brother Mansour, made significant contributions to Lebanese music as a composer, musician, and poet. On September 26, 1972, Assi suffered a severe hemorrhage on the left side of his brain. He was immediately taken to the hospital, where doctors attributed the hemorrhage to potential genetic factors, excessive smoking, or lack of rest. Despite the family's wealth, media coverage highlighted their financial struggles during Assi's illness. Media personality Nidal al-Ahmadiya reported that Hafez al-Assad contacted Fairuz, Assi's wife, offering financial assistance. She declined, saying, “Your people are more deserving than us, and we can secure the money.” Ziad Rahbani, Assi's son, later confirmed that Hafez al-Assad had sent 50,000 Syrian pounds to help with medical expenses. While the family did not deny this, the Lebanese media extensively covered Assad's aid to the Rahbani family.

These three notable cases exemplify the financial struggles faced by many Lebanese and Arab artists in their later careers, particularly as they become vulnerable in old age. While these difficulties may arise from artists' economic mismanagement, they often result from a lack of government-provided insurance. The issue has recently gained attention with the case of prominent Egyptian novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, as numerous Arab literary figures and intellectuals have called for securing funds for his medical treatment in Egypt.

As a regular follower of the Arab cultural and artistic scene, I assert that Ibrahim's case is not an isolated issue, as the deaths of intellectuals and artists in the Arab world often reveal governments' failures in caring for their citizens in old age. As Moroccan writer Said Montassib writes in the New Arab, creative individuals frequently face the fate of anxiously walking into illness and pain, only to die in silence. In the absence of adequate healthcare and amid financial distress, many Arab writers and artists are abandoned — isolated in public hospitals, cold rooms, or immense despair — as if existing cultural institutions are pleased to see them worn down by illness and silenced by pain. Although this is hyperbole, the consequence ultimately leads to isolation on two fronts: the first through illness, followed by marginalization. In truth, providing care for these individuals can transform their desolation into hope.

Sonallah Ibrahim is not alone, but one of many who face these conditions. In a region plagued by widespread corruption, government attention is focused on the privileged few who have built careers as sycophants by aligning themselves with those in power. Those who refuse to conform quickly realize that their intellectual or literary contributions carry little weight when faced with illness or challenging social circumstances.

Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous (1941-1997) wrote his final masterpiece, “The Drunken Days,” from his sickbed while battling cancer. Another notable Syrian poet, Muhammad al-Maghut (1934-2006), quietly withdrew into near-total isolation as illness overtook him. Both experienced immense suffering in their later years, reflecting the struggles of artists in neighboring countries like Lebanon and Egypt.

Maghut passed away on April 3, 2006, at 72, following a prolonged illness. Known for his scathing sarcasm and profound reflections, he once remarked, "I want nothing; I've spent my whole life running, and all I've reached is old age... Oh, weavers, I want a shroud wide enough for my dreams!" Despite his physical decline, confined to a wheelchair and relying on a cane, he continued to find small pleasures in life. Maghut's legacy includes numerous poetry collections and plays, such as “Joy Is Not My Profession” and “Here's To Your Homeland, I Will Betray My Country,” as well as the film “The Border.”

Known for their defiant natures, these writers often conceal their pain rather than begging or surrendering to authorities. Such was the fate of many, like the Egyptian Ibrahim Aslan (1935-2012), who lived with dignity and passed away without adequate health coverage. Other literary figures faced the same fate.

The state should not require citizens to finance their healthcare. A social welfare approach or a more comprehensive state policy that is committed to equal opportunities, fair wealth distribution, and public responsibility for those who cannot afford medical treatment is essential. As Said Montassib points out, some Arab countries, including Morocco, have begun adopting health coverage systems for artists. He writes, "This solution has long been awaited by many Arab intellectuals, writers, and artists who have endured embarrassment."

The Arab press frequently highlights columns and media discussions following the deaths of prominent figures, showcasing posthumous tributes such as elegies, awards, and street namings. Critics argue that these gestures often come too late, neglecting to honor individuals during their lifetimes. More meaningful recognition could take the form of initiatives like supporting cultural institutions, providing publishing opportunities, hosting literary events, and fostering reader engagement. Establishing a dedicated health and cultural support fund, alongside ensuring access to health and social care, could offer security in old age. This might also be a more impactful way to celebrate their contributions.

Arab writers and intellectuals often face abandonment during illness, a recurring tragedy that highlights systemic neglect. Many individuals endure physical and social isolation, lacking access to proper healthcare or social protection. This is especially true as they frequently pursue careers independent of state institutions. This double isolation — both physical and institutional — leaves them unsupported by cultural bodies that should uphold their contributions.

A key factor in the Arab author's dilemma is how to maintain independence while avoiding excessive flattery, which can resemble authoritarian tendencies. However, independence comes at a cost: the risk of being unsupported when ill. Intellectuals and artists often resent government policies toward writers, especially when they are honored posthumously rather than during their lifetimes.

Intellectuals and artists often experience financial hardship due to their non-profit careers and government discrimination. Loyalist intellectuals, who are favored by the state, take priority over dissenters. The literature of Arab intellectuals highlights numerous cases of dissidents who suffered or died alone or without adequate medical care.

Montassib cites Nietzsche and Sartre in his article, framing writing as a moral and existential choice rather than a socially privileged career. This perspective aligns with certain governments' justifications for inadequate medical care for writers. It portrays their struggles as inherent to their chosen path, rather than systemic issues that require remedies. Those who utilize these two philosophers engage in ideological whitewashing.

Writers, often regarded as the moral conscience of the nation, are frequently overlooked, a neglect that exposes significant cultural and ethical deficiencies. Montassib's article passionately advocates for a shift in perspective. It urges societies to honor and protect their writers while they are alive, recognizing their invaluable contributions to the nation's intellectual and moral fabric.

Renowned Egyptian author Sonallah Ibrahim, a prominent figure in Arabic literature, has recently been hospitalized at Cairo's Nasser Institute Hospital, reigniting discussions about the poor health conditions faced by Arab writers. The 90-year-old writer, known for his groundbreaking works such as "That Smell" (1966), "The Star of August" (1974), "The Committee" (1981), and "Zaat" (1992), is being treated for a broken pelvis, a stomach hemorrhage, and related complications. Ibrahim's influence extends beyond his literary achievements; he gained widespread attention when he famously declined a prestigious literary award in Egypt, citing political reasons — a decision that resonated throughout the Arab world. His novels remain the cornerstone of modern Arabic literature, reflecting a lifelong commitment to creative and intellectual exploration.

Al-Mahfouz Fudayli, in an article in Al Jazeera*, highlights Ibrahim's simple routines, from his modest home and clothing to his daily activities in public spaces, including buses and the market. Egyptian journalist Khayri Hassan, recalling a 2007 interview at Ibrahim's small flat on the outskirts of Heliopolis, emphasized the writer's rejection of material wealth. Despite his fame, Ibrahim chose to live in a modest 80-square-meter apartment, refusing lavish comforts to remain connected to the Egypt he cherished and served through his work.

*Al-Mahfouz Fudayli’s essay, ‘“The Human Writer”: What’s Behind the Widespread Sympathy for Sonallah Ibrahim in His Illness?” was published in Arabic in Al Jazeera.

Further reading on Lebanese singers Wadi El Safi and Sabah can be found in the articles “Wadi al-Safi: Lebanon’s Eternal Voice” and “Sabah: The Curtain Descends Upon a Great Lebanese Singer & Cultural Icon” by Sami Asmar, which appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 66, 2012-2013 and Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 68, 2015. To read the articles, click on the links below:

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 125, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE