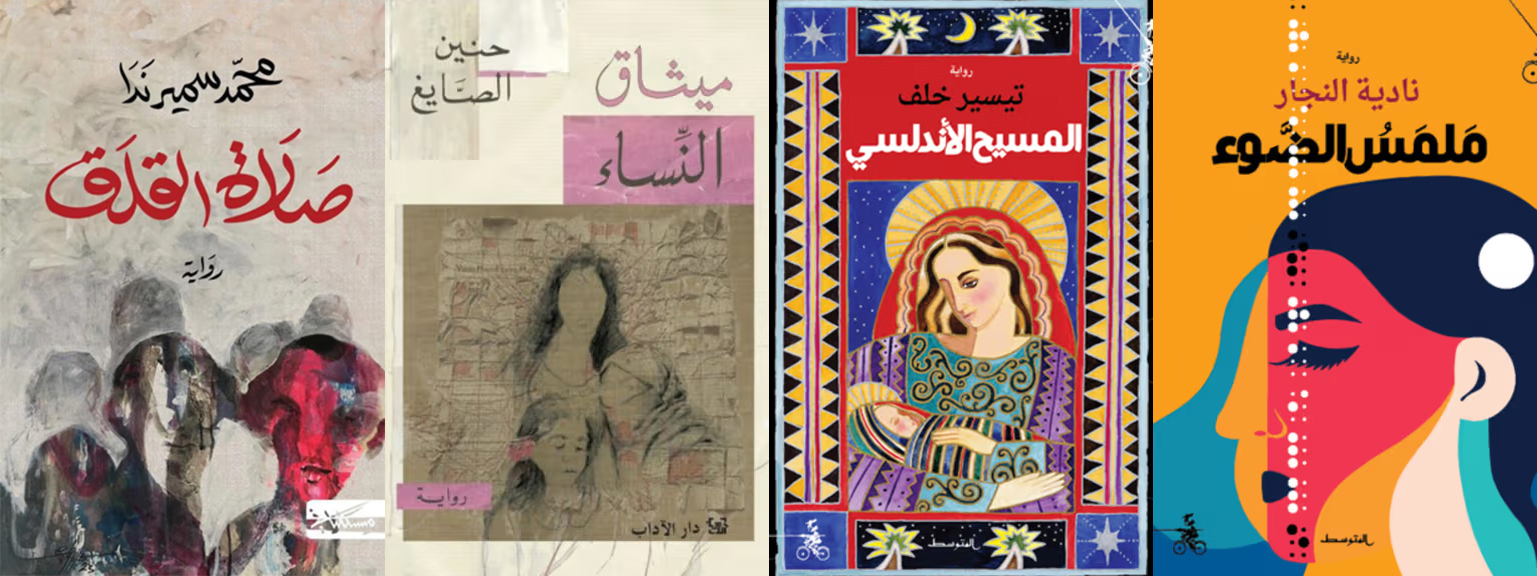

The winning and shortlisted novels of the 2025 Booker Prize. From left to right: “The Prayer of Anxiety” by Mohamed Samir Nada; “The Women’s Covenant” by Haneen Al-Sayegh; “The Andalusian Messiah” by Taissier Khalaf; “The Touch of Light” by Nadia Najar.

Not a year goes by without the same discussions questioning the authenticity of literary prize culture in the Arab world. Since its inception in 2007, the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF), often referred to as the Arabic Booker Prize, has been the subject of scrutiny among literary critics and authors. Ghazlan Touati's article "The 'Booker' and Arab Women Writers... Why the Marginalization?”* in Al Modon takes a gendered approach to a burning question facing not only the Booker Prize, but also the literary awarding institutions across the Arab world: why do women writers rarely win prizes compared to their male colleagues?

The Booker Prize has long suffered criticisms for its lack of transparency in determining its winning candidates, which has done no favors in the ongoing struggles to break the glass ceiling of literary prizes. In the past 16 years, only two women have received the award, once in 2011 (jointly with a Moroccan male writer) and again in 2018. By contrast, 14 male writers have won during that time. In attempts to identify the cause behind the marginalization of women writers in Arab countries, Touati examines whether the issue stems from a lack of women’s participation, publishers’ biases, or the underestimation of women’s literary contributions in the field. According to her observations, the amount of longlisted works authored by women indicates “a decent level of participation and a volume of female literary production that sometimes equals or surpasses that of men,” yet their novels are rarely or disproportionately shortlisted in comparison to books written by men.

However, numbers alone do not adequately explain quality. Touati also considers the potential biases introduced by the gender composition of the judging panels, but surmises that the problem is not likely a result of either the lack of women on judging panels or the lack of participation from women writers. Instead, women disproportionately win literary prizes due to the complex interplay of societal influences, literary tastes, and jury members' subjective backgrounds.

The overarching obstacle for women writers remains societal perception, which she emphasizes cannot be resolved simply by including more women on judging committees, because, as she states, “the fear of being perceived as biased leads them to exclude women first. They share the same mindset as the society around them…They fear being seen as favoring women, which would threaten their credibility and position within these exclusive circles." Women’s issues, mainly women’s literature focused on women’s topics, are dismissed as weak, contributing to the silencing and sidelining of women writers, historically and to the present day. As Touati notes, today’s literary environment operates under a bias that marginalizes themes involving love, sexuality, and domestic life as “less serious” and “personal” topics, and as a result, reinforces a “hierarchy that aligns male experience with universality and female experience with particularity.” Touati argues that social prejudice, not literary merit, is the main culprit behind the dismissal of works written by women within the literary prize industry.

Beyond gender, however, the Booker Prize faces glaring questions about its negative influence on literary production. Though widely considered a crowning achievement for established and aspiring writers, some critics attack the prize as an institution, particularly its Gulf funding sources.

According to Jaber Mohammed Mdkhili in “The Arabic Booker: The Last Literary Supper or the Beginning of the Story,”** published in Al Majalla, the prize offers several benefits to its winning authors, among them prestige and international recognition, guaranteeing financial success to the author’s work. However, the prize can also be a double-edged sword. Mdkhili points out that intense scrutiny and pressure can overwhelm some authors, potentially impacting their creative process and public image, and leading to the tension between the prize's potential to elevate authors' careers and the risk of their work being overshadowed by stereotypes or misinterpretations in the global market. He states that authors may self-impose censorship, stifling creativity in favor of tailoring their writing to what prestigious prize committees seek.

Mdkhili also notes that the Prize inadvertently encourages creative stagnancy, observing that some Booker winners did “not demonstrate a clear desire to sustain their upward creative trajectory after their moment of recognition.” He said, “Winning was an end rather than the beginning of a broader, bolder literary path.” As a result, writers have a diminished desire to experiment or confront creative challenges, begging the question of whether literary prizes motivate writers or temporarily freeze them.

Alaa Farghaly echoes these sentiments in his article “Arab Literary Prizes and the Standardization of Literature: How Do I Write an Award-Winning Novel?”***, criticizing the standardization of literature. As Farghaly writes, “Writers see prizes not only as financial rewards but also as public proof of existence, talent, and legitimacy” — in other words, as a measure of their worth. Literary prizes, which should be an incentive, instead become a constraint, leading writers to shape their works around the perceived expectations of the judging committees. Rather than writing for stylistic experimentation or authenticity, writers may “consciously tailor their themes and narrative structures or even insert token political or social content (e.g., conflict, gender, identity politics) to appeal to the preferences of specific juries.” Farghaly accuses the Booker Prize jury of promoting a “narrow literary aesthetic” under the guise of neutrality and objectivity, stating that “this aesthetic privileges politicized content wrapped in 'sober realism” over stylistic experimentation, genre blending, or postmodern playfulness.” As a result, bold or controversial works get sidelined. Recognition becomes devalued, with “surface-level social media reactions replacing serious critique.” This poses a serious problem for the future of literature, where books are shaped not by necessity, vision, or risk but by trends, marketability, and the tastes of prize committees. This can produce a homogenized literary field where originality is sacrificed for strategic appeal.

*Ghazlan Touati's essay, "The 'Booker' and Arab Women Writers... Why the Marginalization?” was published in Arabic in Al Modon.

**Jaber Mohammed Mdkhili’s essay, “The Arabic Booker: The Last Literary Supper or the Beginning of the Story,” was published in Arabic in Al Majalla.

***Alaa Farghaly’s essay “Arab Literary Prizes and the Standardization of Literature: How Do I Write an Award-Winning Novel?” was published in Arabic in The New Arab.

This article appeared in Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 120, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 AL JADID MAGAZINE