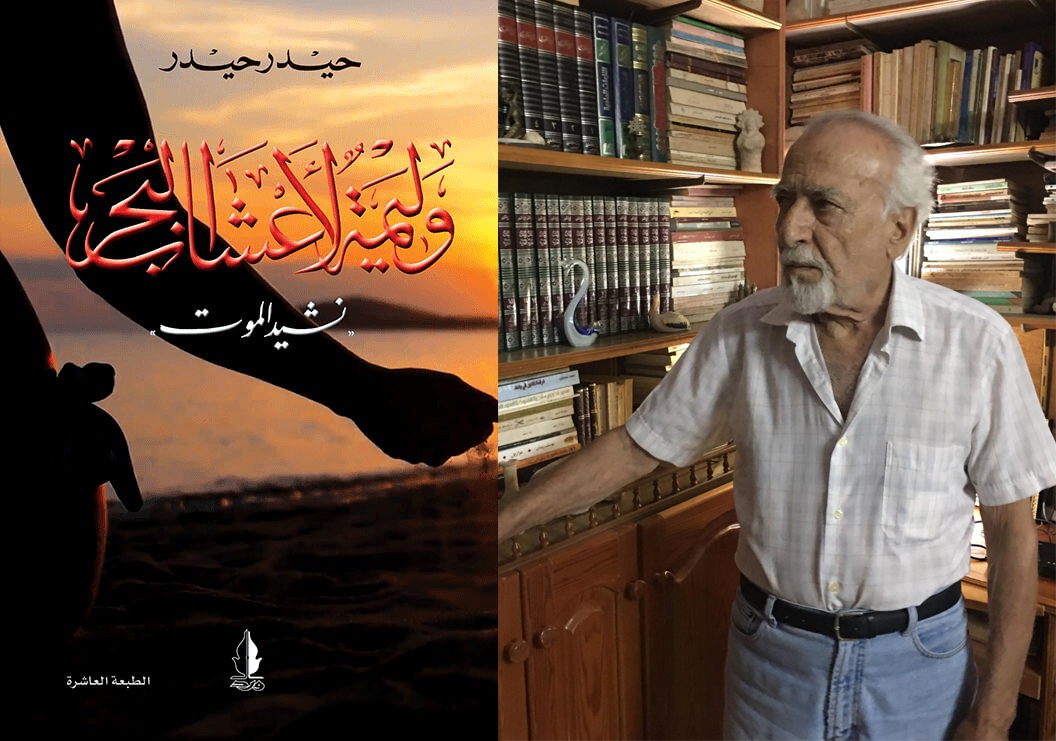

Photograph of Haidar Haidar from Independent Arabia.

Walima Li Aashaab Al Bahr (Banquet For Seaweed)

By Haidar Haidar

Beirut: Dar Ward, 1983

An Iraqi proverb says, “Two pomegranates do not fit in one hand”; they cannot be carried simultaneously. This proverb applies to various issues, including the art of novel writing, especially when attempting to combine politics and art. Few novels integrate these two elements, and Haidar Haidar’s “Walima Li Aashaab Al Bahr” (Banquet for Seaweed) makes another attempt. Does it succeed?

The novel’s protagonist, Mahdi Jawad, is an Iraqi Communist who rebels against the Communist Party leadership and takes up arms against the Baathist government, which seized power in 1963. Jawad and his comrades find temporary refuge in the Ahwar region and launch several military operations against the government. Still, the Baathists mercilessly crush the Communist movement, killing several rebels, wounding others, and forcing some, including Jawad, to flee the country. He finds himself in Algeria, teaching Arabic in the small town of Muna.

In Muna, Jawad meets Asia al-Khudr, a beautiful young woman whose father died in Algeria’s War of Independence. Asia’s mother remarried, and although they pretended to be happy, her stepfather abused her mother and her sister.

The romantic relationship between Algerian Asia and the Iraqi Jawad, locally called “foreigner,” is met with hostility. Some Algerian youths regularly follow Jawad, making his life complex and fraught with danger and surprises. Jawad becomes obsessed with his fears and walks the streets armed, ready to defend himself. He feels he is being attacked by ghosts who appear and disappear without pattern or warning.

As time passes, the dangers multiply, and he receives actual warnings — that the city is cruel and violent, that Algerians do not like foreigners, and that if his relationship with Asia is not severed, he will be robbed and slaughtered.

Jawad is an adventurous revolutionary who refuses to give up; on the contrary, his love and defiance intensify. He pursues his relationship with Asia with purity and seriousness, who reciprocates in kind despite the threats. One day a group of Algerian youths breaks into his apartment while Asia is visiting. She defies the intruders, but she loses her reputation and Jawad his apartment.

When Jawad asks Asia to marry him, she does not turn him down outright but suggests postponing marriage until she completes high school. The harassment continues, ever-increasing. The danger reaches its peak on a beach. Jawad sees a black man with a dagger hanging on his waist, soon joined by a group of attackers. Jawad brandishes his knife, and the tension subsides only when passers-by approach. The attackers disappear, but Jawad is alarmed.

When Asia completes high school, she visits Jawad and gives herself to him, spending the night at his apartment, and he again brings up the subject of marriage. When Asia returns to her own home the following day, Jawad leaves his apartment, almost drunk with happiness, and walks the streets until he reaches the ocean. Then his body is thrown into the ocean, hence the title, “Banquet for the Seaweed.” The author appears to have left the end intentionally ambiguous. We do not know whether Jawad committed suicide or was the victim of a homicide. This summarizes the novel’s plot, the first of the two pomegranates. The second pomegranate recreates the political history of Iraq after the Baath Party ascended to power in 1963.

The hero in the novel is a Communist who is critical of the rightist position his party adopts during the regime of Abd al-Karim Qassim. Qassim overthrew the Hashemite monarchy in 1958, but was overthrown himself by the Baathists in 1963. Harshly critical and analytical, Jawad believes that his party could have seized power and crushed the conspirators but lacked the necessary drive, enabling the Baathists to kill and arrest thousands of Communist leaders and members and to fire an undisclosed number from their jobs. Enough others agreed with Jawad to cause a split within the party leadership. Aziz al-Hajj led the secessionists, adopting Che Guevara’s revolutionary approach to overthrowing the Baathist oppressive regime.

However, the movement did not succeed, and all its members surrendered to the Baathists. Al-Hajj revealed the names of his comrades — who were arrested and executed — in exchange for a job as Iraq’s representative to UNESCO in Paris.

Haidar details the uprising in Al Ahwar and the continuing events of the 1958 Revolution, leading to the Baathists seizing sole power in 1963. Since the period Haidar covers marks the heyday of pan-Arabism and Nasser’s influence beyond Egypt’s borders, he offers additional details of the assassination plots by Nasser’s strongman in Syria, Abd al-Hamid Sarraj, during the Unionist 1958-1961 period. Al-Sarraj hated Communists and concocted plots by the Baathists, Arab nationalists, and other mercenaries in Al Musul, Baghdad, and the Hilla. The novel also gives equal attention to the February 8, 1963 coup, when Baathist state control culminated in unprecedented terror that forced Communists to confess under torture. Haidar relates that the National Guards killed their leader, Salam Adil, the party's Secretary General, along with his comrades. The account includes atrocities such as the massacre of about 500 Communists in Kazmieh, the murders of soldiers and officers with suspect loyalties, the barbaric method of killing Kassem, and the Communist Party’s attempted uprising in July 1963, known as the Uprising of Hassan Sarieh, which ended in more massacres.

Political and ideological messages dominate Haidar Haidar’s “Banquet for Seaweed.” As a result, the novel’s artistic venture becomes subject to historical and political judgment. Haidar’s overemphasis on politics weakens the novel, becoming more of a political pamphlet, disorienting readers and losing them with dull and unnecessary details. A prime example is when Haidar begins, “that in the secret meeting in the Kazimieh suburb, Mehdi talked to his party cell about the present situation, defining in clear points the two schools of thought in the party; one advocating popular struggle; another, led by Zafer, propagating a ‘deviationist’ direction...” This discussion continues for more than 10 pages, and similar passages can be found throughout the book up until the novel’s end.

While novelists should not be persecuted or their works banned for tackling religion in Arabic literature, the religious commentary in Haidar’s “Banquet for Seaweed” is not germane to the novel's theme. Haidar’s novel can stand independently without the gratuitous religious personalities that accomplish little other than provoking the militant and the intolerant. Factual errors, mainly dealing with Iraq’s geography, culture, and landscape, further weaken the novel. These mistakes could have been averted had the author familiarized himself more with Iraq.

In “Banquet for Seaweed,” Haidar attempts to carry several pomegranates and has not paid attention to how many of them he drops on the way.

Translated from the Arabic by Elie Chalala.

This review appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 31, Spring 2000.

Copyright © 2000 AL JADID MAGAZINE