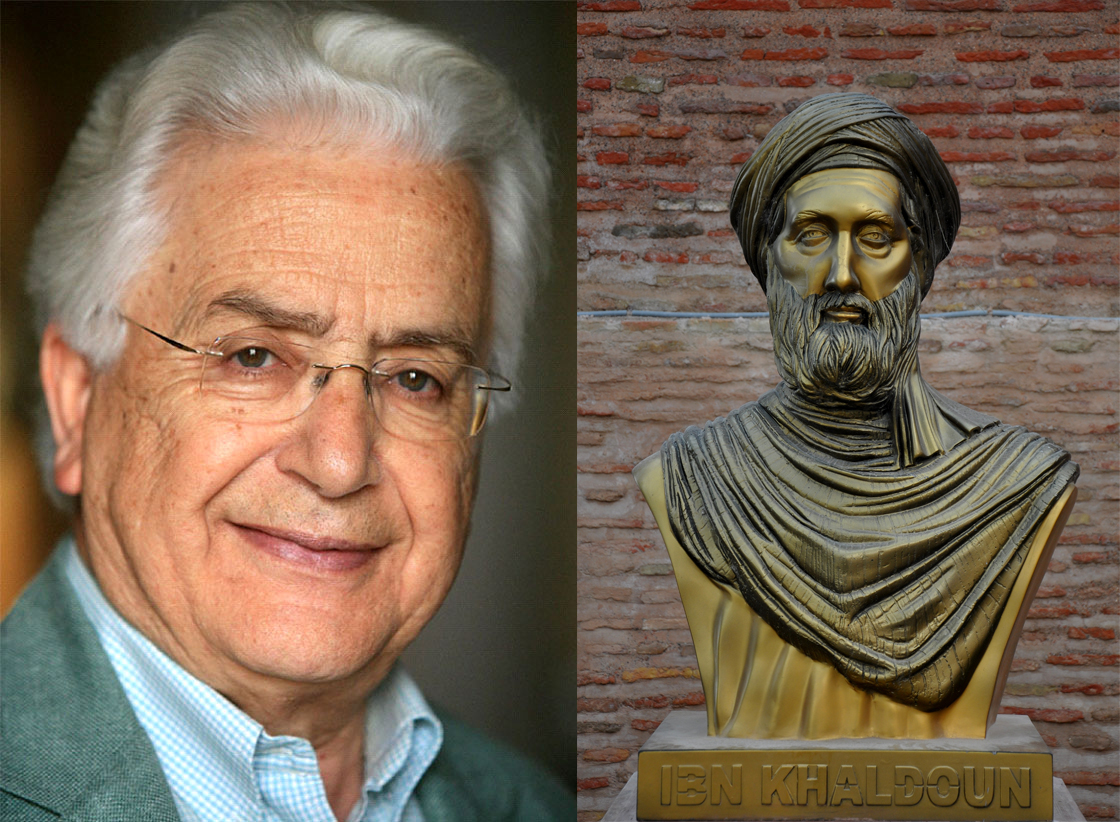

On the left, photograph of Mohammed Arkoun by Corbis via Getty Images. On the right, bust of Ibn Khaldun located in Casbah of Bejaia, Algeria.

Syrian author Hashem Saleh has established himself as a critic, known for his searing criticisms of Amin Maalouf and other influential writers (his complaints of Maalouf’s “The Sinking of Civilizations” were covered in Al Jadid, Vol. 24, No. 78, 2020). He levels his latest claim against an Arab giant, the Enlightenment thinker Ibn Khaldun, calling on scholars to examine the celebrated Arab historian, whom Saleh calls a fundamentalist. According to Saleh, we should not consider Ibn Khaldun a pioneer of free, enlightened, and tolerant thinking in the Arab Islamic heritage. Rather, Ibn Khaldun’s rejection of pluralism and support of jihad sets a tone of intolerance that offers little in today’s turbulent climate of religious wars, unrest, and the rise of Islamic extremism and Daesh.

The brunt of Saleh’s claims come from the findings of the late Algerian scholar Mohammed Arkoun, who spent his life dismantling sectarian rifts and achieving a rapprochement between Abrahamic religions. Arkoun’s work has expanded the horizons of Islamic thought, particularly his research on Golden Age scholars.

Ibn Khaldun made essential strides in urbanism, sociology, historiology, and in his studies on the rise and fall of civilizations. However, Saleh claims he should not be uncritically glorified; the ancient Enlightenment thinker sought to make people believe in Islam, if not voluntarily, then by force — a stance contrary to the Quran’s support of pluralism and a harmonious relationship between all Abrahamic religions. Ibn Khaldun’s famous book “Muqaddimah” (Introduction) dedicates a chapter to the “invalidation of philosophy and the corruption of its impostor” and accuses other philosophers like Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina of being “led astray from God” because they believed in Greek philosophers, according to Saleh.

The Islamic Golden Age witnessed multitudes of intellectual thought. Ibn Khaldun’s environment must be considered when examining his beliefs. According to Saleh, he lived in an era of decadence, generally hostile towards critical rational thought, and was not alone in his fundamentalist beliefs. Other religions like Christianity and Judaism shared traits of isolation and fanaticism during this time. The Islamic world of the Middle Ages was similarly characterized by isolation and intolerance, what Arkoun specifically termed as “takfiri fundamentalist theology.”

However, Ibn Khaldun’s thoughts do not represent the only theological position of his epoch. Other philosophers like Miskawayh, Abu Hayyan al-Tawhidi, and Abu al-Hasan al-Amiri opposed his “intolerant, close-minded stance,” as Arkoun discussed in his state doctorate on Arab humanism in the fourth to tenth centuries.

Previously isolationist and intolerant religions have undergone many changes since the Middle Ages, a modernization that distanced them from fundamentalism. The Middle Ages had been exclusionary, while modern times are more tolerant and open to pluralism. Today, European Christianity has recognized the legitimacy of other religions, including Islam, its historical arch-enemy. It has “abandoned the monopoly of the divine truth” as well as the concept of holy war — the equivalent of Islam’s jihad — and now does not and cannot impose faith on people. While during the Middle Ages, Europe had only recognized Catholicism, today, European countries are more open to a wide variety of religions, according to Saleh. The Christian Church embraced Enlightenment ideas, a change that occurred in the 1960s during the convening of the Second Vatican Council and is seen today in Pope Francis’ humanitarian stances.

However, while these significant theological revolutions have occurred in Europe throughout the past two centuries, they did not happen in the Islamic world. An Enlightenment revolution has failed in the Islamic world’s “deeply entrenched obscurantist thought.” In the words of Saleh, “For this reason, our people are suffering from the huge divisions and explosions of sectarian and confessional fanaticism… the problem is religious before it is political. These explosive fanaticisms prevent the formation of national unity and threaten to divide the already divided. In this atmosphere of confusion, anxiety, and terror, no one trusts anyone.”

Unfortunately, the bold and critical questions that thinkers like al-Farabi, al-Tawhidi, Ibn Sina, and other Golden Age pillars had posed are questions we can no longer ask in today’s climate of reaction and fundamentalism. According to Saleh, “One can no longer cite al-Ma’arri’s sayings about ‘freedom of belief’ or Ibn Arabi’s timeless verses about ‘the religion of love.’ Anyone who repeats these ideas is looked down upon and suspected of being a foreign agent. Ironically, what was possible a thousand years ago is impossible a thousand years later, in the 21st century.”

Until the Islamic world embraces a new Enlightenment revolution, it will continue to be consumed by turmoil and conflict. As Saleh suggests, the first step may be to acknowledge the fundamentalist roots of Islam’s most influential thinkers and turn towards other more open-minded and tolerant intellectual currents.

Hashem Saleh's article appeared in Asharq al-Awsat.

Further reading about Hashem Saleh’s thoughts on Mohammed Arkoun and his book “Towards a Critique of Islamic Reason” can be found in Al Jadid, Vol. 17, No. 64, 2011.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 26, Nos. 82/83, 2022 and Inside Al Jadid Reports, No. 28, 2022.

Copyright © 2022 AL JADID MAGAZINE