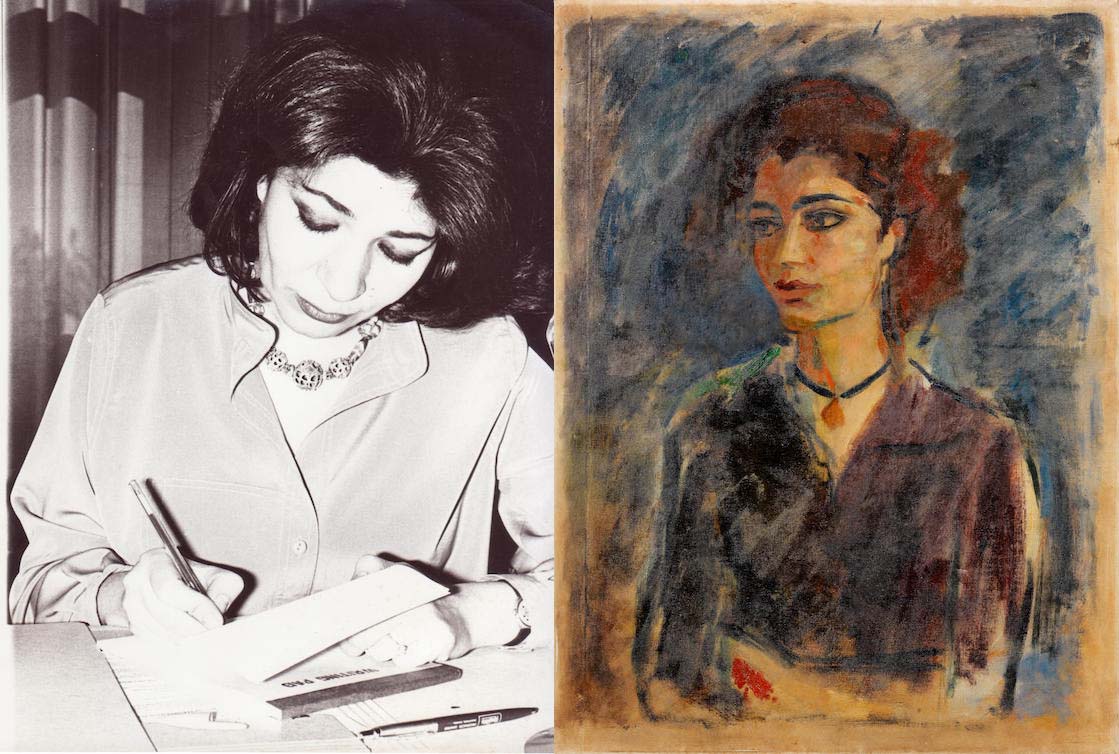

From left to right, photograph of Lamia Abbas Amara from Bonhams and “Lamea” (1949) by Jewad Selim.

Lamia Abbas Amara rose to prominence among a group of poets who ushered in the free verse movement in Arabic poetry. She was not only a major cultural figure and freethinker, but also a pillar of contemporary poetry in Iraq alongside great poets like Badr Shakir al-Sayyab and Nazik al-Malaika. After years in exile, the poet died at 92 in a California hospital due to illness. In the words of Farouk Youssef of al-Arab newspaper, Lamia is best known for her “poetic tenderness, female seduction, and strong presence on stage,” becoming an important icon of Iraqi poetry.

Lamia was born in 1929 in Baghdad in the Al-Kuraimat area to a Sabaean immigrant family of ancient Semitic roots (a group of people who ruled Saba in south western Arabia in the 6th century AD.) She practiced Mandaeism, a monotheistic Gnostic religion. She came from a family of creatives and craftsmen (her uncle, Zahron Ammar, was a gold and silversmith). At the age of 12, Lamia began writing poetry, publishing her first poem in the New York-based Al-Samir magazine, founded by Lebanese poet Elia Abu Madi, a member of the Pen League (Al-Rabita al Qalamia), a contemporary of the Arab-American poet Kahlil Gibran, and a friend of her father. She was deeply affected by her father’s absence due to his travels and only being able to see him for two months at a time, up until his death, as cited by Ahmed Al-Dhafiri, professor of Arabic language at Samarra University. Her nickname came from the city of Amara, where her father was born.

Lamia studied at the Higher Teachers’ House College of Arts (now known as the University of Baghdad) to become an educator, a rarity among Iraqi women in the 1950s. Here she met and studied alongside the many prominent poets of the age: Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, Nazik al-Malaika, Abdul Wahhab al-Bayati, Abdul Razzaq Abdul Wahed (her cousin), and others.

After graduating, Lamia served as a member of the administrative board of Union of Iraqi Writers in Baghdad from 1963 to 1975, a member of the administrative board of the Syriac Synod in Baghdad, deputy permanent representative of Iraq to UNESCO in Paris between 1973-1975, and director of culture and arts at the University of Technology in Baghdad. In 1978, she emigrated from Iraq to escape Baathist rule and lived in several European countries before settling in the United States in the mid-1980s. She told Afaf Nash in an interview with Jadaliyya, “I was wanted and my pictures were shown on TV and newspapers. Judgements were issued against me such as dismissal from my job, the transfer of my property, and even the death penalty.”

The poet published several collections of poetry, among them “The Empty Corner” (1960), “The Return of Spring” (1963), “The Songs of Ishtar” (1969), “They Call It Love” (1972), “If the Wizard Prophecies” (alternatively titled “If the Fortune-Teller Had Told Me,” 1980), “The Last Dimension” (1988), and “Iraqiya” (1990). Her poems were characterized by romance, nature, and freedom, denouncing crime and dictatorship. Lamia also often wrote about women and the repression they suffered, as in her poem “Me and My Abaya,” which “mocked the restrictive garments imposed on women in conservative Islamic societies,” according to the art website Bonhams. In the words of the Iraqi critic Ali Hassan al-Fawaz in Al Jazeera, “She did not set red lines in front of expressing women’s different feelings” and wrote about these feelings boldly. He attributed this to her Sabean religion, which did not prevent her from addressing various women’s issues, as happened with other poets.

Language and folklore fascinated Lamia and distinguished her poetry from that of her peers. Lamia wrote classical poetry in the standard Arabic language and free verse like others in her generation, but also devoted herself to writing vernacular poetry, using the colloquial Iraqi dialect. She studied the relationship between the Mandaean language and Sumerian, as well as the roots of the Iraqi vernacular in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Mandaean. According to Independent Arabia, Lamia found the colloquial language brought her closer to her local audience. Unlike her contemporary Nazik al-Malaika, she wrote about ordinary people’s lives rather than philosophical subjects. Farouk Youssef described how she drew people in with a “vocabulary of nostalgia for a homeland that is slipping through their fingers like air.” Her poetry was beloved by many, so much so that some sentences were repeated like aphorisms, and entire poems were turned into songs by Iraqi artists. In exile, she wrote short poems in the Iraqi dialect, celebrating the San Diego Iraqi community that showered her with love.

Unlike her peers, Lamia’s poetry avoided political subjects, favoring romantic themes and conservative, if not parochial, in nature. She was not affiliated with the Communist Party, or any organized party for that matter, although she aligned ideologically with the left. She said in an interview with Afaf Nash, “I am for freedom, for democracy — for open democracy, not colonial democracy...I am against the poet’s affiliation with a party. The poet is free and the party is a parrot; the poet leads and the party is led.”

She continued, “I do not believe in the principles of communism because they are against two human instincts: the characteristic of possession, which is an instinct that appears in man since childhood, and the characteristic of worship, an instinct in which both the ignorant and educated are equal.”

Unlike many Arab poets, Lamia refused to glorify any Iraqi officials through her works. According to Aya Mansour in Daraj, while living through the various regimes that ruled Iraq, Lamia refused to praise any official of any level, including Saddam Hussein. She said in an interview, “I write about love, people, and place, and I do not write about heads of states. It's not intentional, but it's not my profession.”

Just as her poetry was known for its romantic subjects, much of Lamia’s personal life was surrounded by speculations and to some extent secrecy about her romantic relationships — particularly with Badr Shakir al-Sayyab. She had a close relationship with al-Sayyab, with whom she often exchanged poems while they were students. She wrote “Scheherazade” as a gift for him in her second year of college, and he responded to each section with a poem. Their relationship, however, was “limited to smiles and the exchange of looks,” according to Al Modon. Many poets of the time believed al-Sayyab was more honest about his feelings than Lamia. She influenced one of his most well-known poems, entitled "Love me because all those I loved before you did not love me." She told Afaf Nash, “My memories with him are beautiful. He was as generous as any Basrawi (of the city Basra), tender-hearted, though smoked a lot. He was kind, and at times irritable and tense...We [the students] would sit around him, enjoying his sweet talk and poetry. His recitation was wonderful as if he acted the poem sometimes.”

A quarter of a century after Al-Sayyab’s death in 1964, she dedicated her poem “The Curse of Excellence” to him, stating in a press interview that she had loved him, as cited by Al Modon. The poet Ali al-Jundi, as cited in a tweet by Basheer al-Bakr, suggested that if she had expressed her lamentations towards al-Sayyab while he was alive, his death would have been delayed. However, circumstances — health and religion — had been the major obstacle between them, as Lamia told Afaf Nash. She suffered from illnesses since childhood, including permanent difficulty breathing, and al-Sayyab contended with his own illness, which claimed his life early. She also valued her independence and personal standards. She told Iraqi novelist Inaam Kachachi, “He was suspicious and distrustful of women and couldn't believe that I reciprocated his feelings. I am not required to swear to him that I love him. I had my arrogance, my pride, my self-confidence.” In another interview with poet Saadia Mufreh for the website Fawasel, she said, "Badr was a great person, and I am sorry that I could not meet his request for engagement because I was anxious. I remain an independent personality, and the association of a poet with a poet cancels it.”

Lamia had several other friendships. During her stay in Beirut following her exile from Iraq, she befriended several notable figures, including the Lebanese singer Fairouz. In the words of Suleiman Bakhti in Al Araby, Lamia adored Beirut, and the feeling was reciprocated: the Lebanese state honored her with the Order of the Cedars for her literary merits, though she was unable to accept the medal due to the outbreak of the civil war. She lamented on Lebanon, "On what chest do I place the medal while Lebanon is a wound in my heart that sleeps."

Lamia also studied painting under the Iraqi painter Jewad Selim, who replaced Khaled Al-Jadir as her teacher at the Higher Teachers’ House College of Arts. He often painted and sculpted her. The painting “Lamea” (1949) was a part of his personal collection until it was sold in 1971 (10 years after his death) to Iraq's preeminent art critic Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, and later sold to its current owner. According to Bonhams, when Lamia asked if he would sign it, he said he would not as he never intended to sell it. She later spoke about this experience in "Lorna and her years with Jewad" by Inaam Kachachi.

Lamia lived a modest and simple life in exile. She spent the remainder of her life in a one-bedroom apartment in San Diego on an American salary. Despite her modest lifestyle, she remained fiercely proud of her work and values. She told Nash, “But I am proud that I was not a tool in the hands of any party. I wrote what inspired me and did not write the desires of others. I am satisfied with the simple life here in exile. I left everything I owned behind in Iraq and only carried a few things. My books, the souvenirs given to me by Arab poets and writers, are all gone. Even my pictures and family pictures hanging on the walls of our house were stolen. I am a woman without a past.”

“She was a sweet and gentle person, and on the other hand, a strong and coherent person,” said Farouk Youssef. “Her romanticism in art did not fall at the expense of her principled position in life...She lived a life in harmony with her poetry in terms of its prosperity, simplicity, the sweetness of its content, and proximity to ordinary people.” Lamia is survived by her sisters, her son Zaki, daughters, and her grandchildren.

Copyright © 2021 by Al Jadid