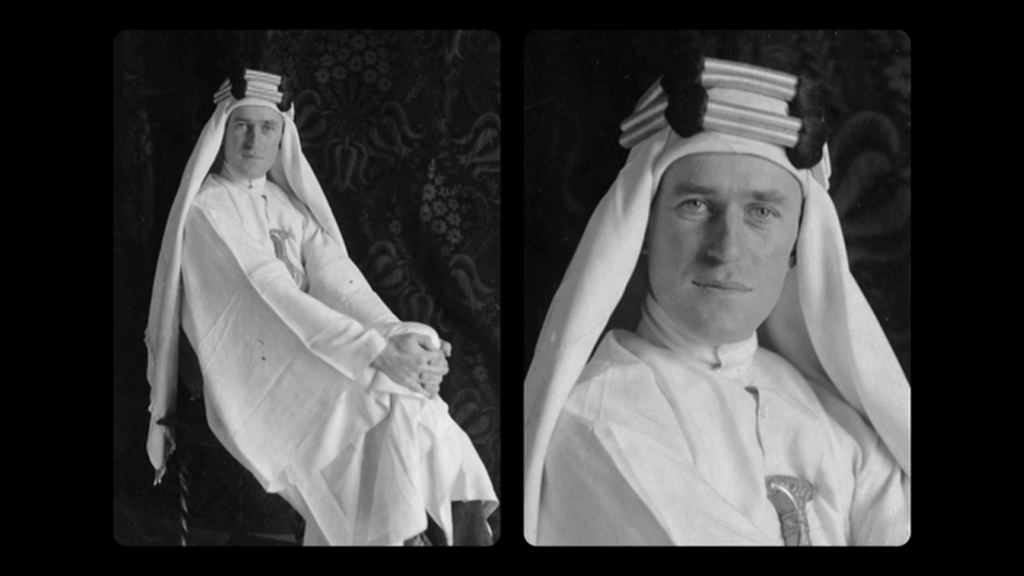

Photo of Lawrence d'Arabie from the film, courtesy of Icarus Films.

The End of the Ottoman Empire

By Mathilde Damoisel

Icarus Films, 2017

A two-part documentary directed by Mathilde Damoisel, “The End of the Ottoman Empire” addresses the decline and fall of the Ottomans. The film deals first with the loss of the Balkan territories and subsequent repercussions, and then with the empire’s losses in the Middle East. The film’s structure and subject matter make it best to approach these two parts separately.

Part I, “The Nations Against the Empire,” deals almost exclusively with the loss of the Empire’s Balkan territories, the legacy of that loss, and its lasting effect on the empire. It opens, appropriately, with a wide angle shot of a Muslim cemetery in present day Sarajevo, thus setting the tone and expressing the filmmaker’s thesis that Bosnia-Herzegovina, with it Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic Croatians and Orthodox Serbs, serves as a microcosm of the Balkanization that occurred in the last part of the 19th century, and, with the carnage experienced in the 1990s, offers the best embodiment of the legacy of the Ottoman retreat from Europe.

The loss of the Empire’s Balkan territories had the dubious distinction of ushering in two of the most heinous scourges of the modern age: the refugee phenomenon and the crime of genocide. According to historian Mark Mazower of Columbia University, one of several renowned historians featured in the film, the loss of about 200,000 square kms as a result of the 1976-1978 crisis caused a massive flow of refugees, mostly Muslim, from the Empire’s former territories. Mazower also adds that the brutal suppression of the 1894 Armenian Sasun Rebellion at a cost of 20,000 people presaged the subsequent Armenian Genocide. This massacre serves as one of several elements in the film in which one finds echoes of more recent trends and events.

Historian Hamit Bozarslan says that while the Ottomans became eventually reconciled to the inevitability of the loss of their Balkan territories, they still wanted to protect the hard core of the Empire, The Turkish center, with a Muslim shell made up of the Albanians, Kurds, and Arabs. Isn’t this almost a direct paraphrase of the neo-Ottomanism foreign policy, favoring a commonwealth with Turkey’s neighbors, and old Ottoman connections? Erdogan pursued this policy, while his first Foreign Minister, later Prime Minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, actively promoted it!

In Part I, Damoisel displays an assured mastery of the medium, avoiding the pitfall of allowing the film to deteriorate into a gabfest of talking heads. Although she features several distinguished academics, she achieves this by skillfully interspersing their statements with archival footage and photography, artists’ rendering of historical events, photocopies of materials from contemporaneous media, animation and even clips from vintage films. The use of archival footage creates a harrowingly surrealistic effect by juxtaposing the jittery, Chaplinesque movement of the characters against a graphic depiction of brutal violence.

Part II, “A Fragmented Middle East,” opens with the statement “From the ashes of its (the Ottoman Empire’s) lands in the East, Arabia, Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine would emerge the Middle East as we know it.” It narrates the story of the ‘Arab Martyrs’ who Jamal Pasha condemned to death by hanging in Beirut, Damascus and Jerusalem. The film features historian Salim Tamari, of Bir Zeit University, and the Iraqi Saad Eskander, who comments trenchantly on Gertrude Bell’s choice of the Hashemite Faisal to be king of Iraq, stating, “He had no place in our history or in our memory.” However, while these historians and others lend a certain depth and a degree of objectivity to the film, the choice of Ambassador Nawaf Salam, permanent representative of Lebanon to the UN, who weighs in with his take on the creation of Greater Lebanon, strikes one as rather odd. One cannot help but wonder how much such a senior representative of the Lebanese Government can deviate from the official narrative!

Part II goes on to deal with the question of Palestine, to which, despite the importance of the subject matter, the film devotes a disproportionate amount of time. Thus, it includes scenes of the Wall and other more recent events, extending the narrative far beyond the fall of the Ottoman Empire, yet pays scant attention to other topical problems such as the Syrian Civil War or the Lebanese Civil War and its continuing legacy.

Unfortunately, Part II falls far short of Part I, so much so, that a viewer, shown the two parts separately, might easily assume them to be the work of different filmmakers. Unlike Part I, which Damoisel bookended with the crisis of 1876-1878 and the declaration of the Turkish Republic by Ataturk in 1923, Part II literally meanders over the map, stretching all the way into the second Gulf War and beyond. And while the filmmaker edited Part I so tightly that at times it attains the texture of a thriller, Part I moves back and forth in time without any rationale, creating an impression of disconnectedness. Viewers can see a striking case in point when the film cuts abruptly from the fight in Iraq against ISIS to the declaration of the Turkish Republic by Ataturk, leaving the baffled audience with the sensation of watching a Quentin Tarantino movie.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 21, No. 73, 2017.

Copyright © 2017 AL JADID MAGAZINE