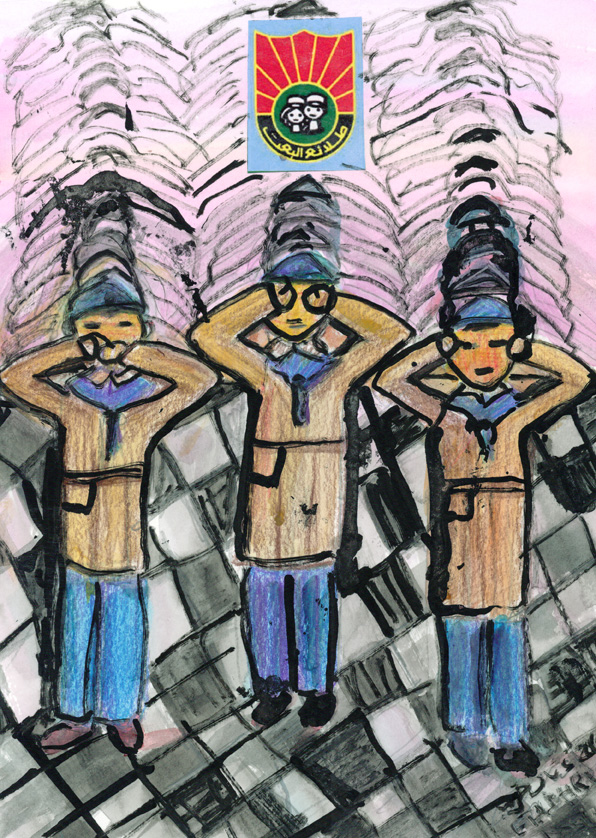

“The Vanguards of the Baath” (2016) by Etab Hrieb for Al Jadid.

For more than five decades, the Syrian child was subjected to an orderly process of upbringing to control the phases of his growth and maturity. Following the nursery phase, which did not have an ideological formation, the child entered the realm of official popular organizations, along the North Korean model, controlling the child’s consciousness and distorting his growth.

Among the new promised generation, ideological series of “brainwashing” continued while accompanied with the development of an intelligence psychology. A seed planted very early, in the beginning stages of their burgeoning awareness, resulted in the “art” of reporting fellow students to state officials. These practices developed in scope as the students gradually advanced in age, all the way until they entered the realm of practical life.

The training for children of the “Baath Vanguards” kept them away from concepts of childhood like freedom and spontaneity. The children were subject to rounds of military training from their early childhood. Instructional political lessons instilled in their immature imaginations misleading concepts about modernism, openness, accepting the other, and pluralism.

This training forced the student to repeat empty slogans consisting of themes like the worship of the individual, along with concepts irrelevant to the child, leaving him unaware of who drafted them or of their moral or even linguistic significance. Some, mistakenly, have resorted to frivolous defenses of the Syrian regime by providing distasteful examples from totalitarian countries or countries hostile to democracy, like former East Germany. In East Germany, advocates truly believed in a clear ideology, although they tried to disseminate it among the youth through rude and poor methods. The former East German methods differed in their respect for the concept of childhood, through which they infiltrated soft and fresh minds in order to implant concepts they believed in and attempted to maintain. In the Syrian case, those in charge of the content of the message, from Vanguard supervisors, teachers, or guides, were in fact detached from the goals of their tasks, and attached instead to their real habits of flattery, submission, and corruption.

During subsequent periods of training, the Syrian youth, subject to the “Union of the Revolutionary Youth,” grew up with the concepts of “securitocracy.” This meant that their successes and prominence depended on their loyalty proven by reporting their peers and even their parents. In addition, mobilization meetings consisting of stuffing, repetition, and recitation of concepts, did nothing to aid the progression or practice of thought, but instead distanced the youth from the basic sources of consciousness, such as reading, and the development of critical thinking and sensitivity. Regardless of whether the man or woman came from a family known for its progressive and nationalist consciousness, their subjugation to this hellish machine erased everything they dared to keep from their parents’ socialization. Only rarely, if their family upbringing proved exceptionally strong, would students challenge the full swing manufacturing of illusion and intellectual poverty. The mainly security personnel, those in charge of socializing the new generation at the most delicate stage of their age, showed no concern for disseminating values or educating young generations about their roles in the collective future of their country and their people.

To arrive at the perfect conclusion of this training, the students entered the college level in parallel to the development of a political-security apparatus called the “National Union of Syrian Students.” Here, “educators” implemented stages of classification, perhaps humorous in appearance, but destructive in reality. Members would label their colleagues from “neutral” to “positive neutral,” or “negative neutral,” among other classifications, which crowded the files of the Union, as well as those of the security branches in charge of these college organizations. Besides corrupting the students’ relationships with each other, the culture of “treason, condemnation, and complaint,” also applied to their teachers, who found themselves subject to the same evaluative standards, unless they happened to be lucky or acted in blind submission to the will of the state.

Generations graduated through this dark tunnel of successive “popular organizations.” While sending children to religious schools offered the only possible form of societal resistance to these popular organizations, the majority of the administrators of those schools tended to hold extremist views. At the time, this did not bother the state, as officials believed that religious indoctrination would teach the students submission and obedience, and would not incite revolts against their superiors, especially when the state closely watched the religious bodies in question.

The phenomenon of private schools returned at a later stage as a result of the weakening of the influence of the “popular organizations.” However, private schools failed to raise student consciousness or initiate constructive debate. In fact, through the teachings of these schools, the youth came under the influence of the negative aspects of foreign cultures, identifying with spiritual and moral impoverishment, which in turn served a new kind of parasitic bourgeoisie, fully connected to the state.

A whole generation has suffered from this backlog of oppression. Yet, despite all the lapses and imperfections of its creations, the genie of repression eventually demanded its freedom and the freedom of its downtrodden parents. Syrian youth will be able to contribute to the process of reconstructing their country, if it will be built on a clear and transparent basis, dependent on civil peace supported by international will, though that goal may have to wait for a long time.

Translated from the Arabic by Elie Chalala. The author has granted Al Jadid Magazine the right to translate and publish his essay.

The Arabic version of Mr. Kawakibi’s essay appeared in the online Huna Sotak.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 20, No. 70, 2016.

Copyright © 2016 AL JADID MAGAZINE