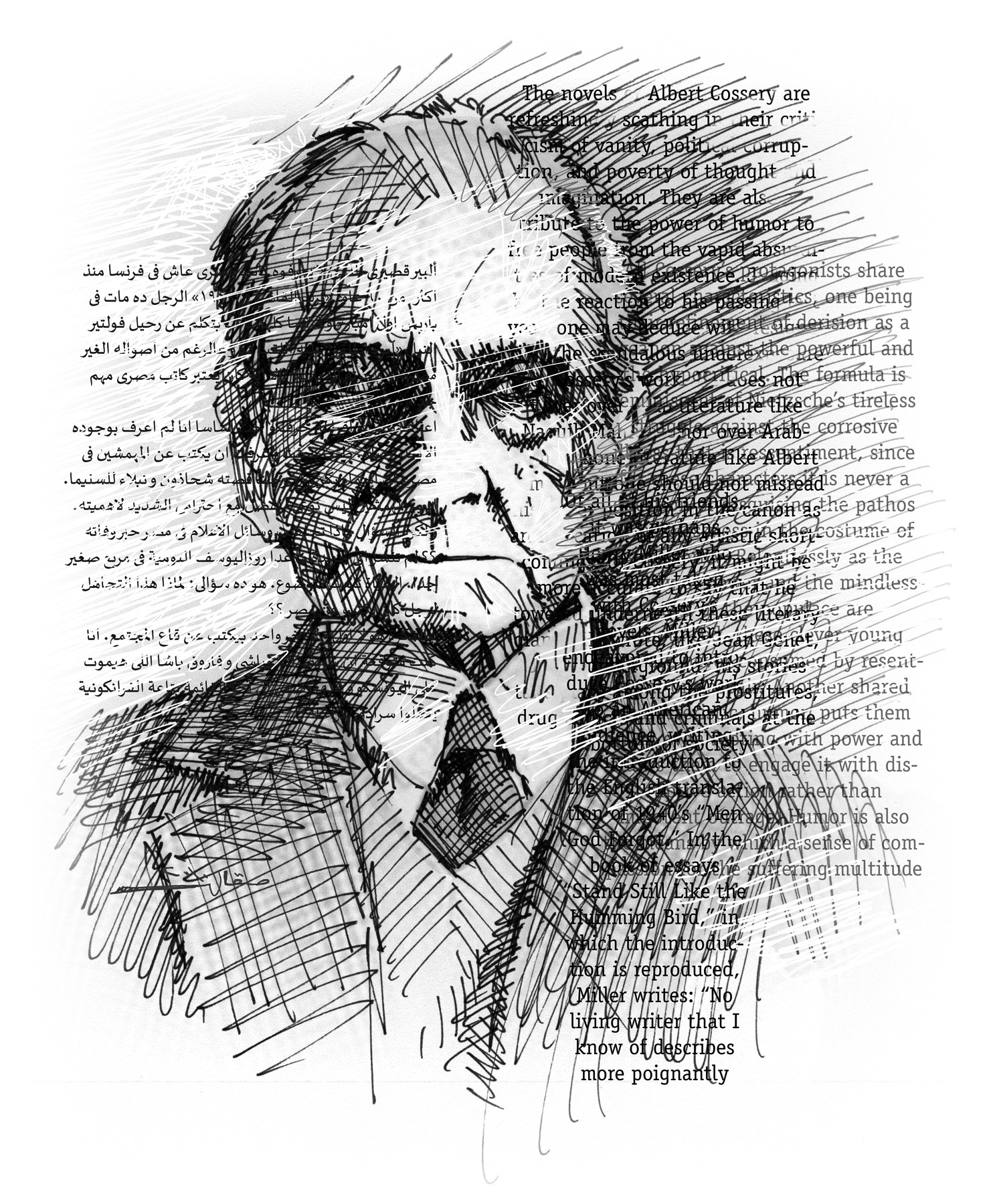

Albert Cossery by Mamoun Sakkal for Al Jadid.

The novels of Albert Cossery are refreshingly scathing in their criticism of vanity, political corruption, and poverty of thought and imagination. They are also a tribute to the power of humor to free people from the vapid absurdities of modern existence. Judging by the reaction to his passing last year, one may deduce with resignation the scandalous underexposure of Cossery’s work. He does not tower over Arab literature like Naguib Mahfouz, or over Arab-francophone literature like Albert Camus, but one should not misread his lesser position as an indication of any artistic shortcomings. Of Cossery, it might be more accurate to say that he towered underneath these literary giants. He wrote, like Jean Genet, of the underground; his stories take place among the prostitutes, drug addicts and criminals at the bottom of society.

Born in Cairo in 1913 to bourgeois parents of Syrian origin, Cossery was educated in French schools in Egypt, and was introduced to the classics – Balzac, Dostoevsky, Baudelaire, Nietzsche and Stendhal—by his older brothers. In his early 20s, he became involved in an art collective by the name of Art et Liberte, which defined itself by its allegiance to the Surrealist movement, as well as by its opposition to the Third Reich’s condemnation of Expressionist art. After a good deal of travel, he moved to Paris in 1940 – motivated in part by a desire to see the Second World War in the flesh. He lived first in Montmartre, and then, after the war ended, in Saint-Germain des Pres, where he passed the rest of his life in one room on the 5th floor of the Hotel de Louisiane. Cossery thrived in the intellectual climate of Paris, of which Saint-Germain was then the epicenter; he knew Sartre, Camus, Durrell, Henry Miller, Giacometti, Tzara, Vian and Genet, amongst others. He was not as productive a writer as his colleagues were, delivering on average only one slim novel for every decade of his life (“only imbeciles write every day” he once said in a French television interview), but each book is carefully crafted in a French that is at once masterful, concise and trenchant in its humor.

Of all of his friends, it was perhaps Henry Miller who was most taken with Cossery’s novels. Miller endeavored to introduce his work to an American audience, writing the introduction to the English translation of Cossery’s 1940 “Men God Forgot.” In the book of essays “Stand Still Like the Humming Bird,” in which the introduction is reproduced, Miller writes: “No living writer that I know of describes more poignantly and implacably the lives of the vast submerged multitude of mankind … (“Men God Forgot”) is the sort of book that precedes revolutions, and begets revolution, if the tongue of man possesses any power whatever.” This rather high-flown praise, typical of Miller when he speaks of his favorite authors, captures something essential about Cossery’s writing.

Each of Cossery’s eight novels depicts the neglected rabble of Egyptian cities and the corrupt state power structure that painfully complicates their already difficult lives. Cossery’s protagonists invariably challenge the symbols of authority by means that are often hilarious, using the labyrinthine underbelly of society as a cover for their operations. In the first scene of 1964’s “Violence and Derision,” a police officer patrolling an affluent neighborhood seeks to rid a street corner of an arrogant beggar, only realizing that the beggar is actually a mannequin when he accidentally pulls its head off while trying to rough it up. The figure of authority becomes the butt of a situationist-style joke, the beneficiary of which is a crowd of spectators who have gathered to watch the scene unfold. The author of this prank is a young, hedonistic interloper named Karim, who with a group of associates wages a campaign of mockery against the corrupt governor of the city.

All Cossery’s protagonists share several characteristics, one being their refinement of derision as a weapon against the powerful and the hypocritical. The formula is reminiscent of Nietzsche’s tireless struggle against the corrosive illness that is ressentiment, since for these characters it is never a question of disguising the pathos of helplessness in the costume of superiority. Relentlessly as the venality of power and the mindlessness of the populace are denounced, these clever young men are never consumed by resentment or despair. Another shared characteristic, humor, puts them on an even footing with power and allows them to engage it with disruptive action rather than impotent outrage. Humor is also the means by which a sense of compassion for the suffering multitude is expressed. And however much Cossery’s characters oppose vulgar materialism, they have no part of political causes. In his novels there is often at least one unfortunate soul naïve and misguided enough to take part in such activism, but the Cosserian hero is far too appreciative of life’s simple pleasures to be distracted by ideological posturing.

From the little we know of his personal life, Cossery seems not to have differed significantly from his protagonists in outlook and lifestyle. In the few substantial interviews with the author that exist, he speaks of his disgust with consumer society, the common denominator of la foule, and mentions on more than one occasion the paucity of his personal belongings, which apparently consisted of nothing more than his wardrobe, his books and some artworks given to him by his friends (those of Alberto Giacometti in particular, which were often sold when money was needed). The comparison to Nietzsche is not accidental – for Cossery, living itself is the highest form of art, and true aristocracy is “that which is detached from this world of consumption, violence and vanity.” All of his heroes faithfully espouse this point of view, eschewing ambition for a more fundamental experience of life, one in which contemplation and enjoyment are the central themes.

All of Cossery’s novels are in some way vehicles for this philosophy, a philosophy that is portrayed as being ontologically at odds with authority, whether it is the authority of the state or the supposed authority of the ego and its hallucinatory self-regard. He often referred to this as an Oriental way of thinking, in stark opposition to the Occident, and it is here that we confront one of the most original aspects of his work. The Cosserian protagonist is not involved in conventional organized resistance, which is peculiar considering the author’s nationality and the era during which he wrote many of his novels. For two decades, the Egypt of Nasser was the political context in which several of Cossery’s books appeared, but unlike his better known contemporaries Mahfouz, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra and Abd al-Rahman Munif, he never refers to the political realities that dominated the era, such as Arab nationalism and Arab-Israeli wars. All the same, his stories are thoroughly preoccupied with a form of resistance in which the relationship between life being lived to the fullest and endeavoring to oppose power is one of necessity. It is an altogether different view of the artist’s responsibility from the one put forth by his friend Jean-Paul Sartre. In the fictional work of the latter, the theme of resistance is always drenched in seriousness and tragedy, whereas for Cossery resistance is itself something to be relished.

One might say that Cossery’s heroes express resistance through their complete detachment, their utter refusal to participate in the shabby constructions, in which the powers that be have ensnared the masses. Cossery therefore occupies a rather rare position in Arab literature, since the writings of many of his contemporaries draw on their experiences of direct involvement in politics (here one thinks in particular of the Palestinians – Mahmoud Darwish, Ghassan Kanafani, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra – but even the more mild-mannered Egyptian Mahfouz engaged issues in a far more specific manner). Cossery’s political imagination seems to express itself mostly through rather generalized themes, and the formula is generally some variation of the idea that the political class of the city is corrupt and the police force is their muscle. Perhaps the only exception to this is 1984’s “An Ambition in the Desert,” a somewhat Munif-esque affair about a small Gulf oil-monarchy, which is the only novel set outside Egypt. Still, this is not inconsistent with statements made by Cossery in interviews, as he often mentions that his appeal, especially to younger readers, is based on his treatment of universal themes intelligible to people anywhere. Though Cossery lived the majority of his life and wrote the majority of his novels in Paris, he always maintained that he never lost his Egyptian identity (though there was one 35-year period during which he did not visit Egypt), that he still thought in Arabic, and that the characters in his stories were always based on vivid memories of people with whom he had associated during his youth in Cairo. By his own admission he never even bothered to apply for a French passport. This appears to be borne out in his work, for even a cursory look at the language used to render dialogue will reveal French that is clearly subservient to Arabic colloquialisms and idioms, though the narration itself is in a very classical register. All the same, there is a nagging sense that the dandyism evinced by his principal characters is too French to plausibly exist in an “Oriental” context. Similarly, the fact that their contrivances against power seem to miraculously work out in the end, and that they usually emerge relatively unscathed, indicates a sort of romanticism on the part of the author that either ignores or simply has no experience of the brutality of most Middle Eastern autocracies.

Surely it would be unrealistic to suggest that Cossery was somehow unaware of the general nature of Arab regimes or any totalitarian regime vis-à-vis criticism, and interviews indicate that the romantic aspect of his work was hardly unwitting. However, considering the Marxist rhetoric of class struggle and armed resistance that were common features of many Arab nationalist movements and the writers that championed them until the 1980s, one can see that, had he been better known, Cossery might have faced accusations of elitism or cynicism from his more revolutionary contemporaries. Such suspicions would have been bolstered by the fact that in a few of his stories the aspiring revolutionary is portrayed as a somewhat clumsy and misguided fellow, more in need of emotional assistance than radical societal transformation. Indeed, the lack of overtly political writing may have contributed to his relatively minor position in the Arab literary world.

There is no doubt that Cossery was adept at portraying with humor, sensitivity and compassion the deplorable living conditions imposed by the strong upon the weak. If we are to take him at his word, he was quite familiar with the indignities suffered by society’s unfortunates, and it stayed with him even during the 35-year absence from Egypt. But, the Arab world being in a constant state of political upheaval, Cossery’s relative lack of resonance among his own people is not so mysterious. Tawfiq al-Hakim and Naguib Mahfouz, to take two of the more celebrated Egyptian examples, wrote of the relationship between the personal, the social and the political, exploring events in a manner in which readers could recognize themselves and perhaps make sense of their own joys and tragedies, as well as the historical contexts that brought them about.

For all his self-professed Orientalism and his distance from the Western world, it was in that same world that Cossery practiced his art. He wrote in its language, albeit in a version that he enriched with the nuances of his native tongue. Perhaps Paris insulated him from the violence, tragedy and censorship that he would have experienced had he remained in Egypt. But we would be wrong to assume that he owes his unique perspective to the Occident – nothing could be further from the truth. Albert Cossery lived at the margins of East and West alike, and would have surely occupied a marginal space wherever he went. The importance of mockery and laughter in his work is paramount; it breathes new life into the idea of resistance, and practically ensures that his stature will increase in both the Arab and French literary worlds as he is discovered by new generations of violence-weary readers.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 61, 2009.

Copyright © 2009 AL JADID MAGAZINE