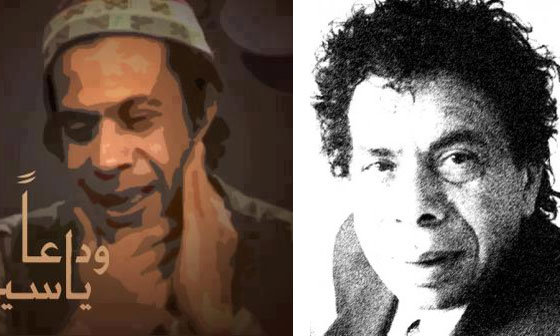

On Sunday, February 24, 2013 Yassin Bakoush, one of Syria’s most talented and adored comedians, was killed as he drove through a rebel-held check-point in the Assali neighborhood. He was on his way home to the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in southern Damascus, an area that has witnessed unyielding combat between the regime and rebels. Not surprisingly, the regime blamed “terrorists” for his death, relying on a rhetoric that has become ever more stale, transparent, and tragic. On the other side, individuals from the Free Syrian Army zoomed in their camera on his blood-stained face, held up his passport for the world to see, and announced that Bakoush had just been murdered by the regime’s rocket-propelled grenade. As both sides callously accused the other, there was no Allah Yarhamhoo, a simple yet necessary phrase attesting to his humanity. In truth, Bakoush was not specifically targeted, but was caught in the crossfire. He died the death of the helpless citizen in a war zone. His was the fate of countless Syrians whose names will remain lost to the world; his life and death illustrate the brutality of the regime.

Born in Damascus in 1938, Yassin Bakoush went on to be become part of the rich assortment of characters in the burlesque, politically-centered comedies of the 1960s and 1970s that founded Syrian drama. Bakoush’s character Yassin al-Ajdab, the oft browbeaten husband, played alongside the power-wielding Fatoon (Nejah Hafiz), Abu Antar the muscle man (Naji Jaber), Ghawwar, the wicked, yet loveable character (Durayd Lahham), the good natured Husni Burazan (Nihad Qalai), and Abu Sayyah, an illiterate and kindhearted strongman (Rafiq Sibayi). Each character’s role changed depending on the plot of the episode or mini-series, but generally maintained his or her personality throughout. These early political parodies — which were first filmed in a studio above the Qasioun Mountains, then moved to Beirut and back to Damascus — were imbued with transgressive political, social, and economic critiques of the Baath socialist project and failed Arab nationalist aspirations. The cycle of corruption, poverty, imprisonment, and lack of opportunity in these stories portrayed a government that intentionally failed its people in order to maintain and legitimize its position.

Bakoush’s naïve character with an ingenuous smile and addictive pout touched the heart of generations of viewers not only in Syria but throughout the Arab world as well. We can remember him in "Sahh al-Naum" (Good Morning, 1973) as the low-level employee in Fatoon’s hotel who spends his day alongside Ghawwar searching for clients to fill the rooms. In one episode, Ghawwar stealthily slips pills in everyone’s coffee to cause memory loss so that he can marry Fatoon. But an air-headed Yassin, who mistakenly serves the potent drink to the man signing the marriage contract, foils his plan. Viewers also cherished his performance in "Milh wa Sukr" (Salt and Sugar, 1973) as the dull-witted husband of Fatoon. After she strikes him, he enters the police station lamenting that since marriage, he gets hit more than he eats. The scene when he finally tries to defend himself ends with him hiding under the bed to escape Fatoon’s wrath. His performance in the mini-series "Wayn al-Ghalat" (Where’s the Mistake?, 1979) is just as delightful. In the episode "Al-Bahth ‘an al-Wazifeh" (Searching for Employment), for example, he plays the kind-hearted friend of Ghawwar and Abu Antar, who asks a relative to help them find a job and is thrilled when he hears they are now residing in a wealthy neighborhood. When he sees them pop out of a trashcan, he is astonished; Ghawwar and Abu Antar answer him in unison, “Your nephew got us a wazifeh (job) that has no barani (extra trips through bribes).” Through the multitude of scenes of innocence, kindness, and grace, Yassin Bakoush continues to touch the lives of his fans.

Yet despite his enormous talent and impressively long career — he continued working in the theater until the age of seventy-five — he had barely enough money to feed himself and resided in a poor neighborhood in Yarmouk. How can it be that after a life full of accomplishment, he lived in utter penury? This tragedy can be attributed to the corruption of a regime, which used culture to gain legitimacy. Both Hafiz al-Asad and Bashar attempted to make intellectuals dependent upon the state in order to co-opt them. This was not simply a question of attempted government co-optation by showering intellectuals with gifts and privileges. The government bestowed favors on an exclusive few to create tensions between artists, in part of their “divide and conquer” strategy. During those early political parodies, while Durayd Lahham stole the spotlight and reaped benefits from the state, Yassin Bakoush was pushed to the margins, referred to as a minor character, and relegated to the life of the destitute. While Lahham has stood by the regime and defended its actions to this day, Bakoush remained silent as he struggled to make ends meet for his family. He did not have the financial freedom to leave Syria and speak out against the regime. As Alawi actress Louse Abdel Karim said from Cairo, like countless Syrians, Bakoush died a random death at the hands of the regime that kills indiscriminately and whose victims are often poor since they have no means of escape. Even though Bakoush was quiet and never outwardly spoke his position, Karim argues that the fact he chose to remain among the poor and refused to leave his neighborhood, speaks volumes. According to her, his death symbolizes the fate of the impoverished.

Yassin Bakoush is another national treasure lost, taking with him his perpetual smile, unaffected gaze, and years of experience that should have been written down as a personal memoir for posterity. In his death, Syria is robbed of a cherished gem, one who belonged to the people.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 17, No. 65, 2011.

Copyright © 2013 AL JADID MAGAZINE