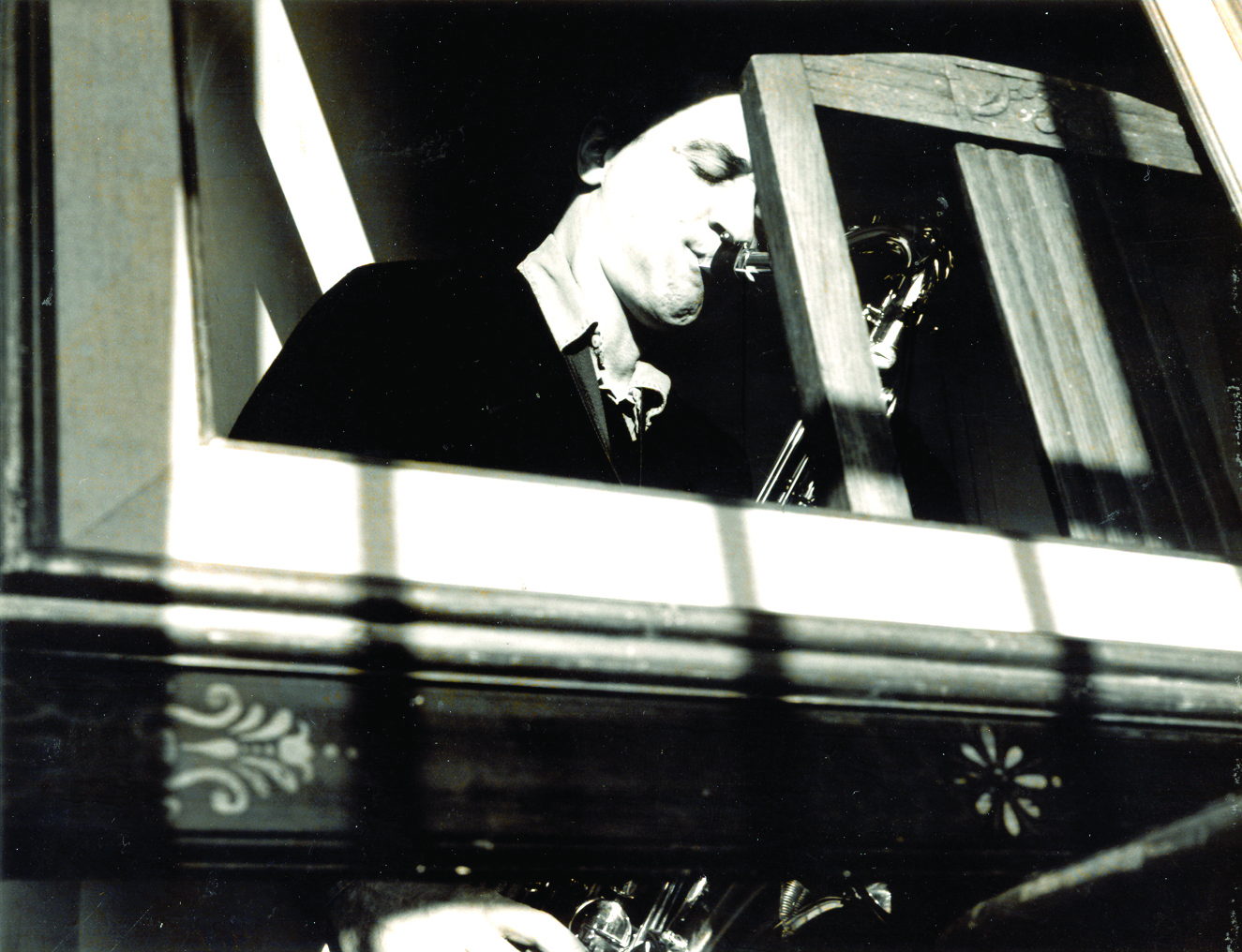

Music is the language composers know how to speak. Their world is synonyms, senses, and specifications from the heart of the tune and the core of the instrument in which they are immersed. Thus, I felt many times, while I was awaiting an answer to a question from Toufic Faroukh, that I was intruding upon this mysterious world which often cannot be expressed in words. The saxophone is the gamble this young man took, immersing himself in the music of the land to which he belongs, and letting the music of the Other world infiltrate the natural tradition. Faroukh's voice is neither defined by geography or language. “I do not find it necessary to define my music and give it an identity; it is the music of this time that takes from this world certain influences and returns them to it through the composer's comprehensive and vast interpretation. My music carries no title except being contemporary,” said Faroukh.

You were born in a country that sings to the rhythm of the flute, the oud, and the drum. How did you reach for the saxophone to connect you with what you are today?

My brother was a saxophone player and he's the one who guided me to this instrument and taught me its ABCs. He was an amateur who instilled in me the love of professionalism. We had discovered the saxophone in the Boy Scouts. The instrument was strange to our environment; unconventional, and used only for certain occasions.

But this instrument seems to have entrapped you.

Yes, but it took a long time, since the end of the 1970s. A good friend, Issam Hage Ali, and I did pretty good work on this instrument and through it, the bond of our friendship strengthened and we became more like brothers. Music was our solace during the bloody events. It was a real flight from the horrors of the time.

When did you leave Beirut?

I got ready to leave in 1984 but before that, I spent 10 years searching for my musical identity. It was then that I was hit by the saxophone “virus.” By great coincidence, I met Ziad Rahbani as well as the late great artist Joseph Sakr, by whom I was greatly influenced. I had an early first experience with Ziad as a player in the play “Binisba Lebookra Shoo” (What is about Tomorrow). I then participated in recording an album “Abu Ali” and joined as an actor in two of Ziad's plays, “Film Ameriki Tawil” (Long American Film) and “Shi Fashel” (Something Failed). In these two works, I explored my theatrical abilities and became interested in this world until I realized one day that music alone could help build my life.

How did working with Ziad Rahbani influence you?

Ziad offered me the opportunity of expression and Fairuz made it possible to accompany her artistically in her 1982 American tour during which the saxophone was my constant partner.

At what level of musical scale is your instrument?

Yesterday I was in love with the alto saxophone, playing melodies. I always found at this level what I seriously search for in modern music. In my compositions and in every project, some type of saxophone is required. But what I prefer and have become comfortable with is the soprano saxophone, which I find soft and delicate and quite close to my voice. I also like it the same way I like Miles Davis, the trumpet player. Davis' voice through his instrument comes back to me while I play the soprano saxophone.

What do you mean by modern music? What are its characteristics? Is it the modern classical music?

When I moved to Paris, where I studied music in the conservatory and in the Advanced College of Music, saxophone was my first goal. My familiarity with it emerged through modern music, particularly the alto saxophone. As for the modern classical music, except Ravel and the French composer Claude Debussy, who introduced the saxophone in some of their rare works, this instrument was not used by classical musical orchestras. When we say modern music, I presuppose the music that was written in the 20th century for a saxophone and orchestra or saxophone and piano. After the 1950s, writing for the saxophone increased significantly.

When you say the saxophone, jazz comes to mind.

In fact, I did not study jazz and its roots at all, nor played jazz on the saxophone. Despite what I learned from the musical institutions in Paris, I am still a self-made musician, who learned and composes by himself. I went searching with this instrument and found that the love I have for it brings out dormant obsessions in me. None of the other musicians were able to help me express them as I wished. Since then, I started writing my music.

What did you learn from these experiments?

My first album was “Ali on Broadway.” It was received positively by the specialized musical press. Four years later, in 1998, I produced my second album, “Asrar Saghirat” (Small Secrets). It's a musical, redolent with a taste of the East and its colors/types; and then another one called “Drabzine” (Banisters). In it, there is a mixture of traditional music.

It appears that your pre-1990s musical experiments left no effect upon you.

Rather, they inspired my talent to write. My experience with Ziad and Fairuz, especially working with them, and recording in the studio, led me to the peak of my pleasure and to a great sense of difficult responsibilities. This experiment taught me and helped refined my abilities, particularly through the work Ziad assigned to his father, Asi, where my instrument accompanied every rhythm.

Then there was your second period in Paris.

Radwan Hatit, a musician friend living in Paris, encouraged me financially and morally to record what I was writing in that period. He is the one who produced my three works. My meeting with him was a miracle, for it relieved me of the financial burden.

Did you introduce different types of instruments right from the beginning?

In every project, there are 20 to 24 players, and I was often forced to divide the recording into a group playing in the West and another playing in Lebanon. After that I used to construct the exact mixture. I believe the oud of Charbel Rouhana is unparalleled, as well as the percussions of Ali al-Khatib's flute and qanun.

Where do you find your inspiration to compose? Is it from your memories?

No. I am not a nostalgic man, but I do have a long-range memory. At times my topics come from sitting on the street. The road has an echo of freedom regardless of how crowded it is with people. In it, I feel loneliness. The road is not my inspiration, but the freedom given to me by the road is my road to the idea–the idea loaded with transitory images, transitory scents.

How do you embody the fragrance of your music?

Oh, what a wonderful idea! It enters the senses in an individual chemistry and from there transforms to a rhythm. Though I avoid sinking into poetics, I feel at the same time that I assume the responsibility of my poetic senses without being caught up in it. It is from the archives of my memory, which I cannot run away from or deny.

Translated from the Arabic by Elie Chalala.

This interview appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 45, Fall 2003.

The Arabic version of this interview appeared in An Nahar. The author granted Al Jadid the exclusive right to translate and publish.

Copyright © 2019 AL JADID MAGAZINE