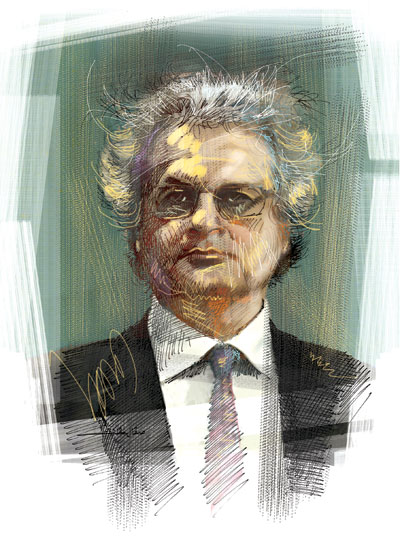

Amin Maalouf by Mamoun Sakkal for Al Jadid.

Amin Maalouf, perhaps the most famous and popular member of the French Academy, is a best-selling author and known as an intellectual whose works “honored” the French language. Maalouf’s contributions are considered an answer to the call of the Academy, whose exclusive and main concern is safeguarding the French language and preserving French culture. Perhaps none of the Academy’s current members can rival Maalouf’s worldwide fame, even though he follows a distinguished line of intellectuals like Eugene Ionesco, Marguerite Yourcenar, Alan Rob Gray, and of course, Levi Cluade-Strauss who bequeathed Maalouf his seat.

However, great names have passed into the Academy’s immortels in the previous ages such as Racine and Cournet, Montesquieu, Ernest Renan, and Victor Hugo. These names elevated the status of the French language, but now many have disappeared from the Academy’s membership records. Prominent members like Baudelaire, Flaubert, Rambeau and Mallarmé did not originally like the traditional ambiance of the Academy founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635 in the reign of Louis XIII. Of all the immortels in French literature, it seemed there were more outside the Academy circle than inside it. And most of these outsiders entered into the annals of history with only insignificant influence attributed to them.

Amin Maalouf was ready to enter the Academy since the first and second rounds during which his name was “dropped” because of his resistance to traditional francophonism which he criticized for its unconvincing goals and rationalizations. Maalouf infuriated the immortels when he openly supported a famous statement signed by progressive and avant-garde French intellectuals announcing the death of francophonism and the retreat of the French language in the world especially in regards to the rise of American-English language. But his eventual selection in the third round seemed expected and inevitable, because the immortels need a name like Amin Maalouf, which carries a worldwide import. He was without a doubt a great benefit to the French language, carrying it to various countries in the modern world.

Politicians recognized the position Amin Maalouf occupies in France and the francophone world well before the Academy; these politicians include the Presidents Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy who made the author of “Leo Africanus” (Leo the African) accompany them in their visits to Lebanon. And how embarrassing it seemed when President Chirac, in his 1996 visit to Lebanon, introduced his “friend” Maalouf to the three presidents of Lebanon: President Elias Hrawi, Prime minister Rafik Hariri, and House Speaker Nabih Beri. Can you imagine that scene? Lebanese top officials waiting for a French president to convene a meeting between them and a renowned Lebanese author. Perhaps these men found it strange for a novelist to accompany presidents in political missions?

The Lebanese government and media celebrated the “event” of Maalouf’s selection to the Academy differently from France. Since France ceased to pay attention to the Academy, the French press did not highlight the event except in small spaces inside the papers. Yet in Lebanon, the event was mythic and treated as a legendary feat with the press devoting sizable coverage to its front pages. The Lebanese government did not delay in imprinting his picture on silver lira coins, and in the near future postage stamps with his picture will enter circulation. Maalouf succeeded in rising the emotions of the Lebanese when he asked for the cedar tree to be carved into the “sword,” one of the Academy’s symbols, with a picture of Marianne who is an icon of the French Revolution. He truly knew how to address the Lebanese people, and instilled a revival of appreciation among the Lebanese people for everything French. If people like Charles Qorm, Hector Khlat, Charles Helou and Said Aql and other alike, had been able to see this scene, they would have been struck with jealousy and perhaps even envy. For France had been in their view, as Said Aql once described it, an “oasis of modernity” and the “capital of the spiritual world” and the “repository of the rational tradition.” The generation of the French Mandate believed in the close ties between the Lebanese and French literary societies. Amin Maalouf knew well though that France was not as it once was and that the French language now suffers from a worldwide retreat. Additionally, he saw the Lebanese “myth” was on the verge on vanishing with its apostles dead or nearly so in the case of Said Aql as he approaches his hundredth.

When the great Algerian writer Asia Jabar entered the French Academy in 2005, Algerian intellectuals disagreed on her selection, but for most, her induction was not a noteworthy event. In fact, many attacked the Academy and accused it of harboring an imperialist spirit. Major writers like Rachid Boudjedra and Taher Wattar did not hesitate to describe this matter as a farce and argued that Asia Jabar’s affiliation with the Academy would not benefit Algerian or Arab culture, but do quite the opposite.

The Lebanese, as opposed to the Algerians, celebrated the “event” not as a cultural achievement but as a political one. This is the Lebanese “myth” that shines forth in the world, from Cadmus all the way until Gibran.

Translated from the Arabic by Joseph Sills.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 17, No. 65, 2011.

Copyright © 2012 AL JADID MAGAZINE