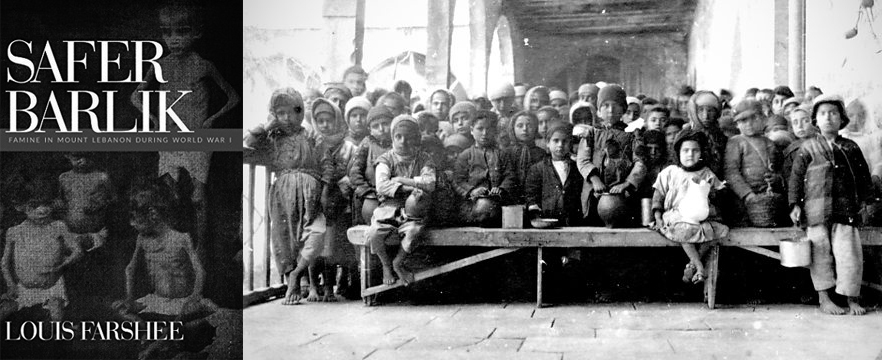

Photograph of the famine in Mount Lebanon, courtesy of BBC.

Safer Barlik: Famine in Mount Lebanon During World War I

By Louis Farshee

Inkwater Press, 2015

Despite his almost uniformly dry and scholarly tone, Louis Farshee’s painstaking reconstruction of the famine that may have claimed as many as 375,000 Lebanese and Syrian men, women, and children out of a population of four million represents a labor of love.

100 years after the perpetrators, survivors, heroes, and villains of this desperate course of events have all disappeared, Farshee has combed and analyzed conflicting records and testimonies so that attention may be paid to the Famine, as to other atrocities of the era, such as the Armenian genocide.

“Safer Barlik” — the phrase for the Famine, translated as “The Exile” in a 1967 Lebanese feature film — traces its roots to the longtime practice of abducting and pressing men in Lebanon, then part of Greater Syria, into Ottoman slave labor gangs. (Safer means voyage; Barlik, Anatolia in Turkish Asia Minor.) Being pressed into these gangs proved tantamount to receiving a death sentence; even if a laborer survived his harsh work term, his masters would release him into the Anatolian wilderness with no resources to return home. Farshee’s research leads him to estimate that only three percent ever did make it back. During the Great War, common usage extended the phrase to cover forced military conscription into the Ottoman army, while at the same time the Ottoman labor gangs expanded to include women.

The 500 year Ottoman rule of Mount Lebanon featured a combination of institutional cruelty and shrewd compromise that, in its last years, tightened its doomed grip to create a series of catastrophes for its subjects. The Ottomans had allowed the indigenous peoples — Christian, Druze, and Muslims — limited self-governance, which created a caste system of shaykh (lord) and fellah (peasant), but kept the area relatively stable until the fall of the Shihab dynasty in 1842.

Internecine violence, a peasants’ revolt, and the 1860 civil war between previously co-existing Maronite Christians and Druze characterized the next 20 years, resulting not only in deep and bloody losses for the less well-organized Maronites, but also the formal assumption by Western nations of the “protection” of religious groups:

“…Orthodox Christians were favored by Russia, Druze, Protestants, and Jews by Great Britain; Maronites, Chaldeans, and Nestorians by France; Latin Catholics by Austria. Armenians, the largest Christian minority in the Ottoman Empire, had no Western protector, although the Russians were their geographic neighbors.”

This history created the climate that led to the Famine. Farshee delineates the five events that put “the perfect storm” in place: “Turkey signing a mutual defense treaty with Germany, the unprovoked and deliberate attack by Turkey on Russia and Russia’s subsequent declaration of war, the halting of all maritime traffic between Egypt and Syria; [the 1915] invasion of the locust, and the Allied naval blockade.”

It dazzles the mind to think of the effect that Turkey’s neutrality in World War I might have had — no hostilities with Russia or the Allies; no maritime blockade of money, supplies, and food to the region (supplied by émigrés, foreign governments, and relief agencies such as the Red Cross) — aid that would have limited the losses from the ravenous locusts and from the greed of some moneylenders and suppliers; no need for the Ottomans to tighten the screws through increased conscription and punishment of crimes from sedition to food smuggling with execution, no Sykes-Picot agreement to partition the Ottoman Empire after the war.

But the Young Turks overruled the Sultan and his advisers, leading to the 1915 genocide of Armenians (with many of the survivors fleeing to Beirut and Mount Lebanon), and to a slow genocide by starvation for the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon.

Farshee attempts to round out his portrait of the hated Jamal Pasha, Military Governor of Greater Syria 1914-1917, by quoting the writings of Halide Edid, a Turkish feminist and educator. Jamal enlisted Edid, with limited success, to establish an Ottoman school system (replacing schools run by the Allies and their supporters), as well as to reform an overcrowded Lebanese orphanage.

Edid also lauded Jamal’s flimsily justified hanging of 11 men (convicted on evidence of treason gained by raiding the abandoned French Embassy and breaking into documents with diplomatic seals) — a 1915 event so burned into Lebanese consciousness that they commemorated every August 21 as Martyrs’ Day.

In addition to his brutality, Jamal proved a poor administrator. In just one example, freight cars of grain intended for Mount Lebanon rotted on Syrian train tracks while to the west, thousands were dying.

Farshee’s narrative becomes most human when he discusses the heroes of the Famine, those groups and individuals who rose to the challenge of mitigating its effects. These include the Druze under Nasib Jumblatt, singled out for the values of cooperation, communality, and hospitality that allowed them to minimize deaths among their people, as well as to save others who came to them for help. Farshee also praises the close-knit Maronite Christian village of Zgharta and one of its leaders, Sarkis Naoum, a generous and gifted smuggler who used his knowledge of the mountainous terrain, Ottoman patrols, and safe routes to distribute thousands of pounds of grain, until his death in a shootout with bandits in 1917.

Farshee includes moving reported details of the struggling and dying: a young mother making a paste out of the bitter berries of the meliaazedarach tree — which even locusts would not eat — to feed her baby; people stuffing their empty bellies with the raw husks of carob pods, until the inedible residue felled and killed them.

These images from long ago linger in the mind of the reader living in a world still beset by malnutrition and starvation, by oppression and injustice. Louis Farshee has added a necessary chapter to the narrative of Middle Eastern history.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 69, 2015.

Copyright © 2015 AL JADID MAGAZINE