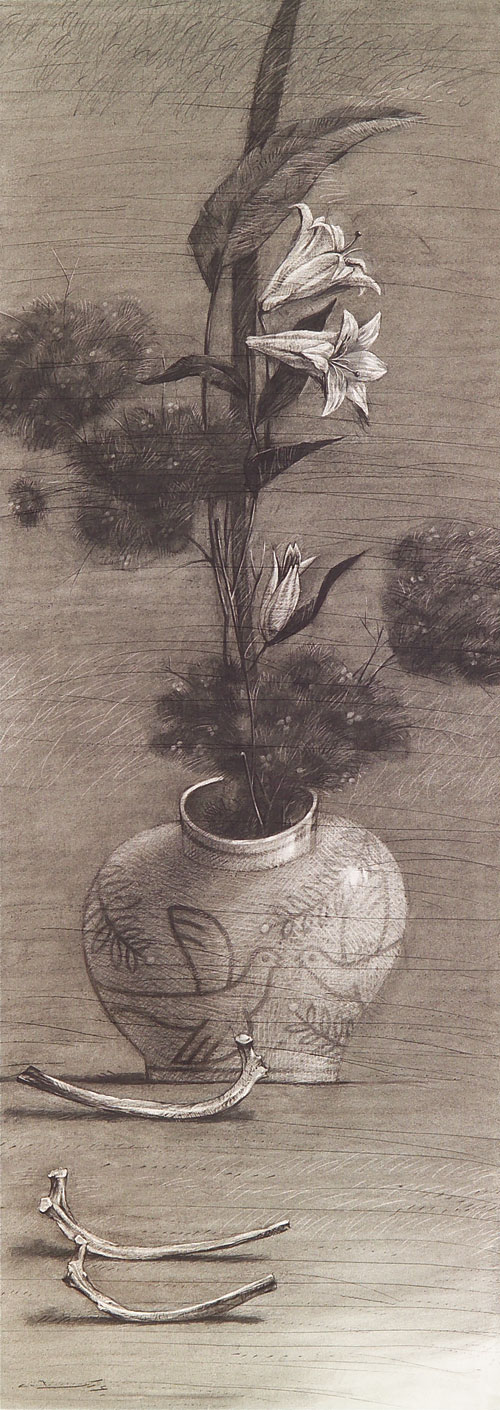

"Untitled" by Youssef Abdelki.

Arab-American literature was already growing by leaps and bounds in the late 1990s, but the Sept. 11, 2001 hijacking attacks fueled an upsurge of interest in all things Arab and Muslim and helped broaden the mainstream appeal of poetry and prose by American authors of Arab descent. More Arab-American writers are getting published, and their work is finding its way into more anthologies of women’s writing and other postcolonial collections, albeit slowly. Challenges remain, to be sure, but we are watching a vibrant new genre of Arab-American literature emerge after a century of struggle for recognition.

Much of the post-9/11 attention sought non-fiction works about the Middle East, Islam, and the situation of women in the region, with little regard for works of fiction – a trend also seen in other areas of the publishing world. Michael Norris of Simba Information analyzed Bowker’s Books in Print database and showed a marked increase in the publication of books about the Middle East and the Arab world beginning in 2003 and 2004. This slight delay reflects the lag time in publishing and interest further bolstered by the Iraq war – although he says the higher numbers have already leveled off. His data shows a steady increase in the number of fiction and non-fiction books published about the Middle East, from 793 in 1997 to a peak of 1,304 in 2004. In 2006, the number dropped back to 1,076.

The sad truth is that even now the centuries-old tradition of Arab letters and philosophy remains largely outside U.S. consciousness. When these works are available in English translation, Arab literary and religious classics are often grouped with Third World literature, emergent literature, and post-colonial literature, something scholar Fedwa Malti-Douglas describes as a “grave injustice” given their rich history. (One of the only Arab writers with a strong publishing record in the United States is the late Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, but his works became readily available only after he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988, the first and only Arab to achieve that honor.)

Contemporary Arab-American writers trace their literary heritage to a group of poets active in the 1920s. The group, known as Al-Mahjar or “the immigrant poets,” included writers from Lebanon and Syria such as Gibran Khalil Gibran, Ameen Rihani, and Mikhail Naimy. Together, these writers sparked an interest in immigrant writing among the mainstream American audience, as writer and critic Elmaz Abinader demonstrated. Rihani, whose works include “The Book of Khalid” (1911) and “A Chant of Mystics and Other Poems” (1921), is often described as the “father of Arab American literature.” One of his most notable accomplishments was to introduce free verse to the traditional Arab poetic canon around 1905.

Gibran not only held a prominent role among the early Arab-American writers but also kept company with U.S. literary figures, such as the poet Robinson Jeffers and playwright Eugene O’Neill. His opus, “The Prophet” (1923), has been translated into more than 40 languages and for many years, it was the best-selling book in the United States after the Bible; today there are some eight million copies in print. Despite his immense popularity, the first serious anthology of American poetry to include Gibran’s work was “Grape Leaves: A Century of Arab-American Poetry,” published by Gregory Orfalea and Sharif Elmusa in 1988.

From the late 1940s through the early 1980s, writers seldom self-identified as Arab-American, although strong independent poets and writers such as Samuel Hazo, D. H. Melhem, and Etel Adnan established their reputations in this time period.

Abinader, an award-winning writer herself, says these writers “distinguished themselves initially as writers independent of ethnic categorization (and) later donned the cloak of the Arab-American identity.” She describes them as a bridge between the two generations, as well as between Arab-American writing and the American literary canon. For instance, Melhem, a noted scholar, and author of the first comprehensive study of Gwendolyn Brooks helped mainstream Arab-American literature by organizing the first Arab-American poetry reading at the annual meeting of the Modern Language Association in 1984 (Abinader). Adnan created her own publishing company, The Post-Apollo Press, which has helped ensure publication and distribution of many works by Arab-American writers. She also served for years as president of the Radius of Arab American Writers, Inc. [RAWI], a writers’ group founded in the early 1990s.

Poets Naomi Shihab Nye, Lawrence Joseph, David Williams, and others made their marks in the 1980s and 1990s, with younger poets following their footsteps, including Suheir Hammad, Nathalie Handal, and Hayan Charara, to name just a few. Diana Abu-Jaber published her first novel, “Arabian Jazz,” in 1993, a book widely described as the first mainstream Arab-American novel. Mona Simpson is another Arab-American writer who has published several novels, but she does not strongly identify as Arab American and the subject is not central to her work.

Several important anthologies and periodicals have helped generate interest in Arab-American literature over the past decade, including “Grape Leaves” and “Food for Our Grandmothers: Writings By Arab-American and Arab-Canadian Feminists,” by Joanna Kadi in 1994. “Post Gibran: Anthology of New Arab American Writing”(1999) showcased recognized writers and introduced newer writers, including Hammad, Hayan Charara, and Mohja Kahf, to a broader audience. Handal won great acclaim for compiling the poetry of Arab women writers, including quite a few Arab Americans, in her book, “The Poetry of Arab Women: A Contemporary Anthology” (2001), which was published by Interlink Publishing and has sold more than 10,000 copies, a phenomenal achievement for a book of poetry in the difficult U.S. market.

Another important collection, “Dinarzad’s Children: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Fiction,” followed in 2004, edited by Khaled Mattawa and co-editor Pauline Kaldas. This year, Charara came out with a new anthology, “Inclined to Speak: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Poetry,” which includes more poets who cover more new ground with their themes and topics.

Clearly, the early years of the 21st century have seen a spate of new works of Arab-American fiction and poetry, autobiographical memoirs, anthologies, and a growing body of literary criticism. However, several factors, including consolidation of the publishing industry and the attendant focus on profitability, anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism, and the increasing conglomerating of bookstores, have continued to limit the number and range of works that are being published. Despite promising inroads, Arab-American literature is still far from integrated into the mainstream of U.S. cultural criticism. Charara concludes that most of the poets included in his anthology remain mostly unknown “not only to the larger public but even to ‘experts’ in the field of contemporary American poetics and to other poets.”

Such continuing obstacles have spurred increasing numbers of Arab Americans to create their own venues to present works of literary and cultural production, a trend that one expects to continue to strengthen in the coming years. RAWI, has been a key driver in this movement, as have its individual members. The organization has grown immensely since its inception and now includes over 100 Arab-American writers and maintains a website that features member profiles and original writing. In 2000, writers D. H. Melhem and Leila Diab compiled an anthology of the work of RAWI members, and the group has begun hosting annual literary conferences to further promote Arab-American literary production.

Playwright Kathryn Haddad founded the award-winning journal Mizna: Prose, Poetry, and Art Exploring Arab America, in 1999, facilitating publication of the work of hundreds of Arab-American writers and visual artists whose work might not otherwise have seen the light of day. This journal, Al Jadid, founded by Elie Chalala 14 years ago, has also played a critical role in showcasing the work of Arab-American writers and critics. New York recently had its fifth annual Arab-American Comedy Festival, drawing a record 1,700 attendees. Handal is helping to found a group based in Britain that plans to stage and highlight Palestinian theater and Kahf is working on an anthology of Muslim-American literature.

Together, these individuals and organizations have contributed mightily to the emergence of a rich and growing body of Arab-American literature, making it more accessible to scholars and students in disciplines such as English, comparative literature, American studies, and women’s studies, as well as the general public. In addition, their efforts have created a national community of Arab-American writers, many of whom previously felt isolated within their own regional communities. This emerging community has helped fuel more collaborative projects and remains a key driver behind events that showcase and encourage Arab-American literary production.

Several years ago, the late scholar Edward Said said the Arab-American community was as in a “gestating stage,” and that there wasn’t quite enough of a tradition of Arab-American literature yet. At that point, he said, the “Arab American simply plays a very tiny, marginal, unimportant role.” The ensuing years have provided some glimmers of hope, and a new age may be dawning. The period of gestation is over, and the community has in fact given birth to a strong, healthy, and growing body of Arab-American literature. Challenges still abound, but the number of venues for publication and distribution is expanding, and a few pioneers are clearing the path for increased access even to big, mainstream New York-based publishers.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 16, No. 62, 2010.

Copyright © 2010 AL JADID MAGAZINE